Forged in Isolation: The Mountainous Heart

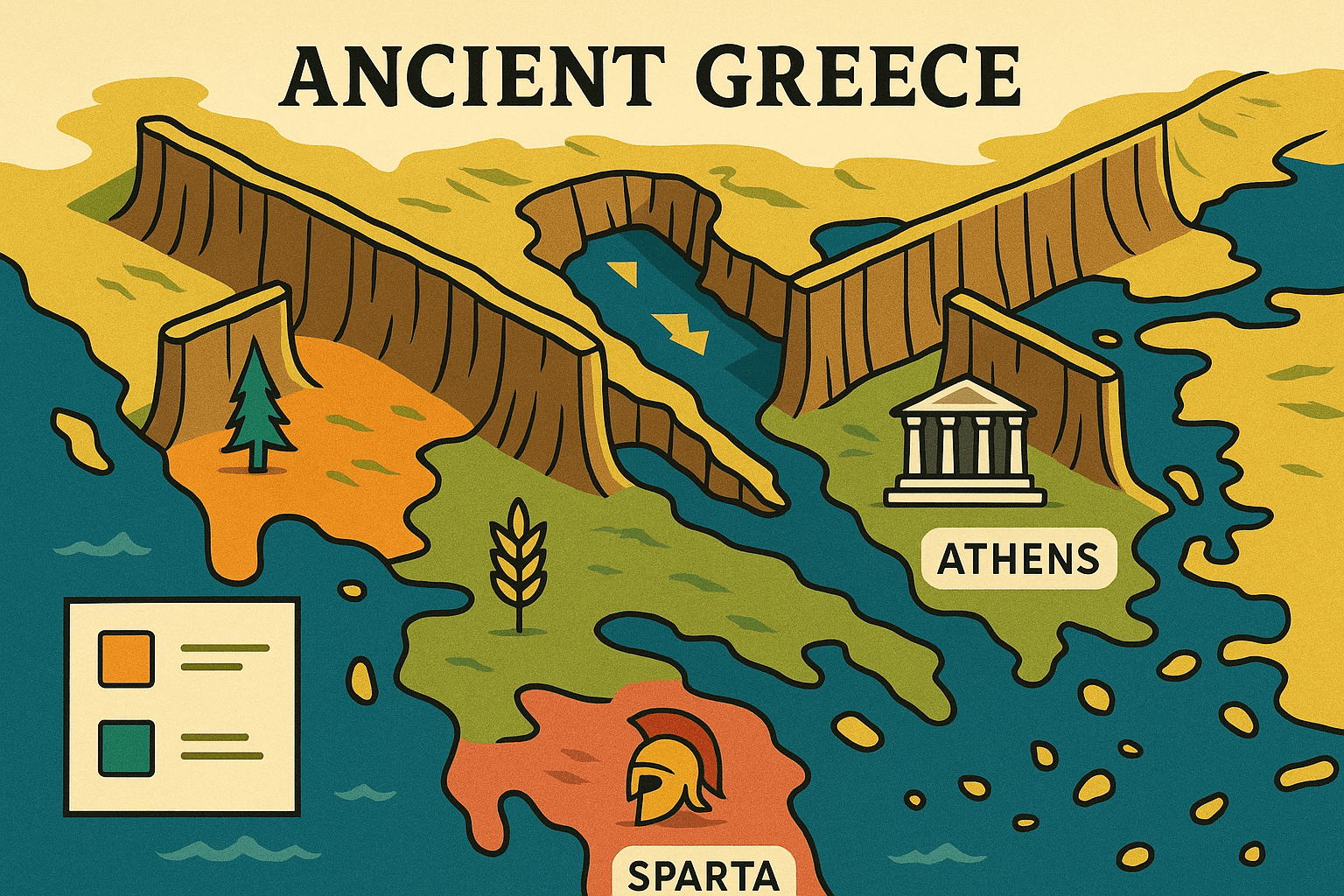

Step onto the Greek mainland, and you’ll immediately understand. Greece is not a land of wide, open plains. Roughly 80% of the country is mountainous, dominated by the formidable Pindus range, often called the “spine of Greece.” These mountains carve the landscape into a mosaic of small, isolated valleys and coastal plains. For the ancient Greeks, this was their entire world.

In an age before modern engineering, traversing these mountain ranges was a treacherous and time-consuming task. It was often easier and faster to sail from one coastal town to another than to travel a few dozen miles inland. This profound isolation had a direct and lasting impact on Greek political and social life. It led to the birth of the polis (plural: poleis), the independent city-state.

Each valley or small plain became its own self-contained political unit, with its own government, laws, army, and patron deity. The people living there developed a fierce and unshakeable loyalty to their home city. They didn’t consider themselves “Greek” first and foremost; they were Athenians, Spartans, Corinthians, or Thebans. This powerful local identity, or “polis-patriotism”, fostered several key traits:

- Fierce Independence: The poleis guarded their autonomy jealously. Any attempt by one city-state to dominate others was met with stiff resistance, leading to near-constant alliances and warfare. The famous Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta was, at its heart, a conflict born from this deep-seated resistance to one city’s dominance over others.

- Cultural Diversity: Isolation bred variety. Sparta, cocooned in the fertile but landlocked Laconian valley, developed a rigid, militaristic society focused on internal control and land-based power. Athens, situated on the Attic peninsula with its excellent port of Piraeus, looked outward to the sea, developing a society based on trade, democracy, and naval supremacy. Their different geographical settings directly contributed to their opposing values.

The Great Connector: A Civilization Built on the Sea

If the mountains were the great dividers, the sea was the great connector. No part of mainland Greece is more than 90 miles from the coast, and the entire civilization is scattered across thousands of islands dotting the Aegean and Ionian seas. The Greeks looked at the sea not as a barrier, but as a liquid highway.

The land itself pushed them in this direction. The rocky, thin soil was difficult to farm and could not support a massive population with grain, unlike the fertile river valleys of the Nile or Tigris-Euphrates. The sea, however, offered a bounty of resources and opportunities. It provided fish for food and, more importantly, a highway for trade and communication.

The Greeks became master shipbuilders and sailors. Their iconic ship, the trireme—a fast and maneuverable warship with three banks of oars—allowed Athens to build a maritime empire. The sea shaped Greek civilization in two crucial ways:

- Trade and Colonization: The sea connected the Greeks to the wider Mediterranean world. They traded their olive oil, wine, and pottery for grain from the Black Sea region, timber from Macedon, and metals from across the sea. When a polis became overpopulated or faced internal strife, it didn’t conquer its neighbor; it sent a portion of its citizens across the sea to found a new colony, an apoikia. This spread Greek language, culture, and political ideas from modern-day Spain and France (like the city of Marseille) to the shores of the Black Sea.

- Naval Power as a Lifeline: For coastal cities like Athens, naval power was everything. Controlling the sea lanes meant controlling the flow of trade, food, and wealth. The decisive victory against the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE wasn’t just a military triumph; it was a naval victory that secured the independence and future of the Greek city-states.

The Land’s Limits: Shaping Diet, Dialect, and Destiny

The specific nature of the Greek land and its Mediterranean climate (hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters) dictated what the Greeks could grow and how they lived. The rocky soil was unsuitable for the vast fields of wheat that sustained other empires. Instead, it was perfectly suited for what historians call the “Mediterranean Triad”:

Olives, Grapes, and Grain. Olives provided olive oil, a source of calories, a lotion, a lamp fuel, and a primary export. Grapes provided wine, a cornerstone of Greek social life and another key trade good. They supplemented these with hardier grains like barley, along with legumes, fruits, and vegetables.

This resource base had significant consequences. The perpetual scarcity of fertile farmland was a constant source of tension and a driver of conflict between neighboring poleis. It also fueled the colonial impulse, as cities sought new lands to feed their growing populations.

Even the Greek language was fragmented by the mountains. While all spoke varieties of Greek, the physical isolation led to the development of distinct dialects. The Doric dialect spoken by the Spartans sounded different from the Attic dialect of Athens or the Ionic dialect of the Aegean islands and coast of Asia Minor. These linguistic differences, while not usually a barrier to communication, reinforced the strong sense of local and regional identity fostered by the landscape.

In the end, the geography of Greece shaped a destiny defined by paradox. The very mountains that prevented the formation of a unified Greek empire also cultivated the fierce spirit of freedom, competition, and innovation that we celebrate today. The sea that served as an escape from poor farmland became the avenue for spreading Greek culture across the known world. The land didn’t just host the Greeks; it actively built them, piece by jagged, sun-drenched piece.