Picture Antarctica. Your mind likely conjures images of a vast, silent, and blindingly white expanse. A continent of superlatives—the coldest, driest, highest, and windiest place on Earth. It appears pristine, untouched, a land belonging to no one and everyone. And yet, beneath this veneer of serene emptiness lies a geopolitical puzzle, a “frozen conflict” where national ambitions are held in a delicate, icy suspension.

While the world sees a continent dedicated to peace and science, seven nations maintain formal territorial claims to a staggering 80% of its landmass. These claims, currently dormant under the Antarctic Treaty, represent a fascinating intersection of history, geography, and international politics.

A Continent Apart: The Unique Geography of a Claim

To understand the claims, one must first appreciate Antarctica’s unique geography. It is a continent without an indigenous human population. Its only inhabitants are a transient community of scientists and support staff, living in isolated research stations. The physical geography is dominated by the colossal Antarctic Ice Sheet, which covers 98% of the land and contains 70% of the world’s fresh water. This ice buries entire mountain ranges, like the Gamburtsev Mountains, and flows towards the sea in massive glaciers and ice shelves.

This lack of a native population and the extreme environment meant that for centuries, Antarctica was a terra nullius—a “nobody’s land.” This status is precisely what opened the door for nations to stake their claims based on principles developed for more temperate, accessible lands.

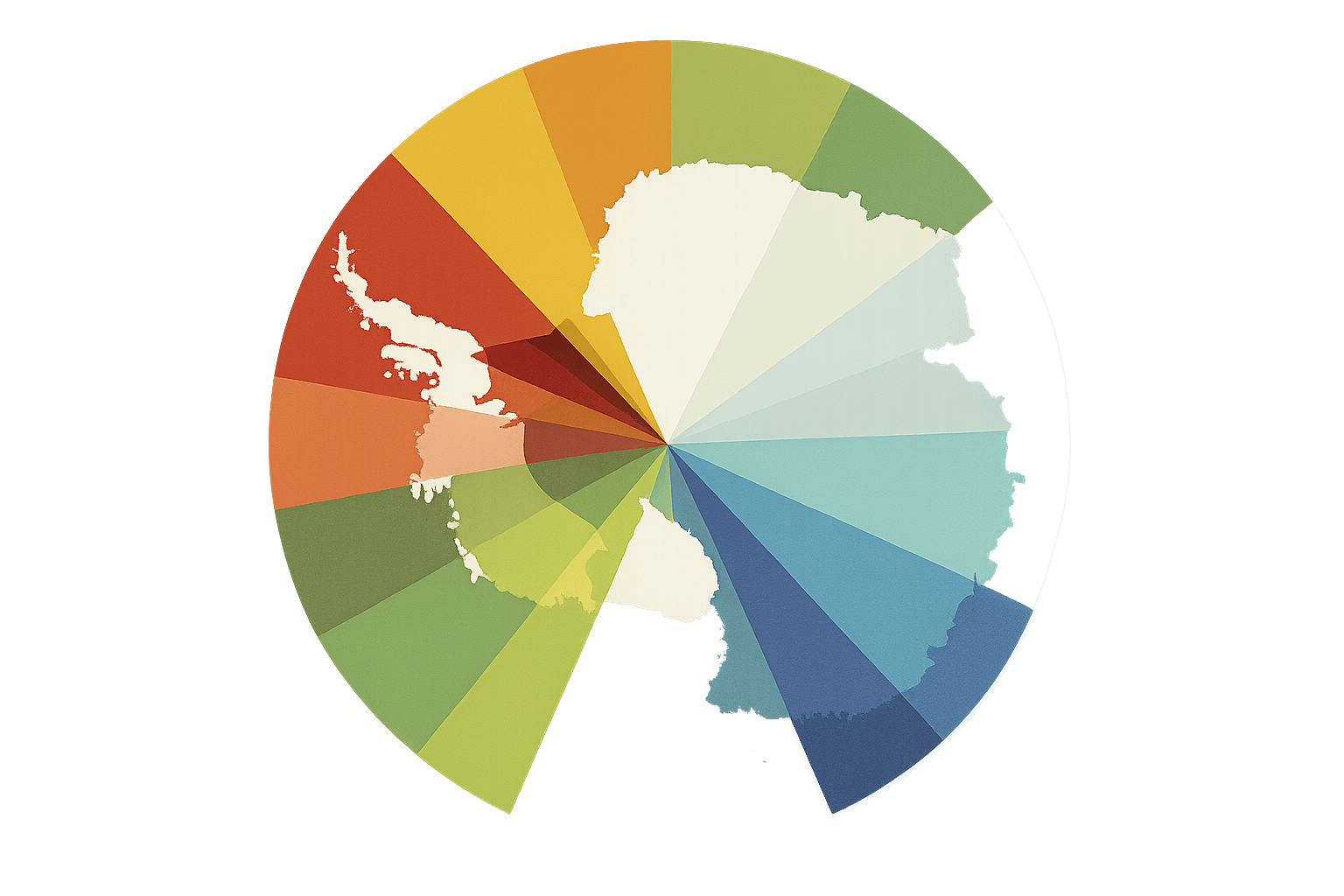

Slicing the Pie: The Seven Claimant Nations

The Antarctic claims are not random patches of territory. Instead, they are almost all wedge-shaped sectors, like slices of a pie, with their tips converging at the geographic South Pole. This “sector principle” is a uniquely polar approach to territorial demarcation.

The seven claimant nations are:

- United Kingdom (claimed 1908): A vast sector that includes the Antarctic Peninsula and the Ronne Ice Shelf.

- New Zealand (claimed 1923): The Ross Dependency, which includes the Ross Ice Shelf and the McMurdo Dry Valleys.

- France (claimed 1924): A narrow sliver called Adélie Land, famously explored by Jules Dumont d’Urville.

- Australia (claimed 1933): The largest slice, covering an immense 42% of the continent.

- Norway (claimed 1939): Two territories—Queen Maud Land and the uninhabited Peter I Island. Notably, Norway’s claim doesn’t extend to the South Pole, leaving its southern boundary undefined.

- Chile (claimed 1940): A sector that heavily overlaps with the British and Argentine claims.

- Argentina (claimed 1942): A sector that almost completely overlaps with the British claim and significantly with the Chilean one.

The most contentious area is the Antarctic Peninsula, the most accessible and biologically rich part of the continent. Here, the claims of the United Kingdom, Chile, and Argentina are stacked on top of each other—a geographical recipe for tension.

The Scramble for the Ice: Historical Basis of the Claims

How did these nations justify carving up an entire continent? They used a mix of historical precedents:

- Discovery and Exploration: The UK based its initial claim on the early explorations of James Cook and later sealers and whalers. Norway’s claim to Queen Maud Land is directly linked to Roald Amundsen’s successful expedition to the South Pole in 1911. Planting a flag was a powerful symbolic act.

- Geographical Proximity: Argentina and Chile argue from a principle of continental contiguity. They view the Antarctic Peninsula as a geological extension of the Andes mountain range, which forms the spine of South America. From their perspective, Antarctica is a part of their southern neighborhood.

- Administrative Control and Occupation: To bolster a claim, you must demonstrate control. This led to a “scramble for the ice” in the mid-20th century. Nations established permanent scientific bases that often served a dual geopolitical purpose. The UK established the world’s first permanent base on the continent in 1944. Argentina went a step further, establishing Esperanza Base, and in 1978, became the site of the first-ever human birth in Antarctica—a deliberate act to strengthen its claim through “native-born” citizens.

The Great Thaw: The Antarctic Treaty System

As the Cold War intensified, fears grew that Antarctica could become a new front for conflict. The scientific cooperation of the International Geophysical Year (1957-58) provided the perfect catalyst for a diplomatic solution. In 1959, twelve nations, including all seven claimants and other active powers like the USA and USSR, signed the Antarctic Treaty.

The treaty is a masterpiece of diplomatic ambiguity. It dedicates the continent to peaceful purposes, bans military activity, and guarantees freedom of scientific research. Crucially, Article IV addresses the claims:

It does not recognize, dispute, or establish territorial claims. No new claims can be asserted while the Treaty is in force.

In essence, it presses the “pause” button. The claims are neither validated nor invalidated; they are simply frozen in time, allowing cooperation to flourish on top of this unresolved dispute.

Cracks in the Ice: Geopolitical Pressures and the Future

For over 60 years, the treaty has been remarkably successful. However, the world is changing. Climate change is making parts of Antarctica more accessible, and technological advancements make resource extraction more feasible. The 1991 Madrid Protocol banned mining activity for at least 50 years, but that moratorium comes up for review in 2048.

Beneath the ice sheets lie potentially vast reserves of oil, gas, and valuable minerals. The Southern Ocean is rich in krill, a vital part of the marine food web and a lucrative fishery. This resource potential puts immense pressure on the treaty’s foundations.

Furthermore, non-claimant nations are increasing their footprint. China, in particular, has rapidly expanded its presence, with four research stations and a fifth planned. While operating under the banner of science, this expansion gives nations a strategic foothold should the treaty system ever falter.

What If the Treaty Fails?

If the Antarctic Treaty were to fail or be abandoned by key signatories, the frozen conflict would rapidly thaw. The seven claimant nations would likely reactivate their claims with vigor. The overlapping wedges of the UK, Argentina, and Chile on the peninsula—a region with echoes of the Falklands/Malvinas conflict—would immediately become a global flashpoint.

A new, 21st-century “scramble for Antarctica” could ensue, this time involving not just the original claimants but also major powers like the United States, Russia, and China, who have never recognized the original claims. This could lead to a chaotic rush for resources, irreparable environmental damage, and the potential militarization of the last continent on Earth dedicated solely to peace.

For now, Antarctica remains a symbol of successful international cooperation. It is a natural laboratory for humanity, governed by a shared commitment to science and peace. But beneath the ice, the lines drawn on old maps remain, a silent reminder that this frozen conflict is only one political meltdown away from becoming a very real fire.