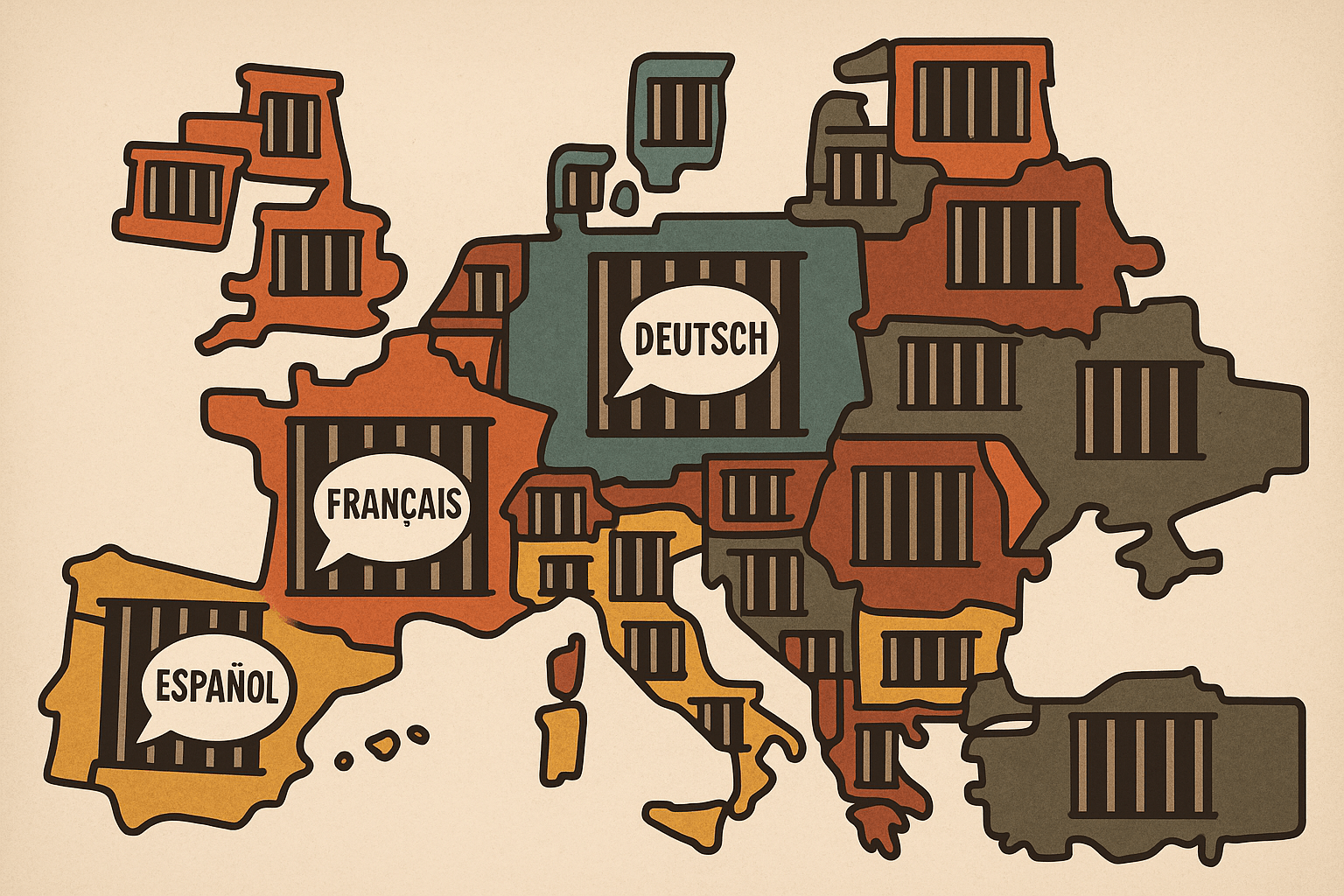

In his seminal work, ‘Prisoners of Geography’, Tim Marshall powerfully argues that the destiny of nations is inextricably linked to their physical landscape. A country’s access to the sea, the defensibility of its mountains, and the fertility of its plains have, for millennia, dictated its politics, its wars, and its wealth. But what if we stretch this compelling idea beyond geopolitics? What if geography doesn’t just imprison nations, but also the very words they speak? Is language, too, a prisoner of geography?

The answer, in short, is a resounding yes. The linguistic map of our world is not a random mosaic; it is a landscape carved, shaped, and flooded by the same geographical forces that build mountains and divide continents. From the highest peaks to the widest oceans, the terrain has profoundly influenced how languages are born, how they evolve, and how they die.

The Mountain Fortress: An Incubator of Diversity

If you want to find linguistic diversity, head for the hills. Mountains are the ultimate barriers. They isolate communities, making travel and communication difficult, slow, and often dangerous. For language, this isolation is a powerful preservative. While languages on open plains might merge, blend, or be conquered, those tucked away in mountain valleys are sheltered from outside influence. They become linguistic incubators, allowing unique dialects and entirely separate languages to flourish undisturbed.

The Caucasus region, wedged between the Black and Caspian Seas, is the poster child for this phenomenon. It is often called a “mountain of tongues.” In a relatively small area, three entirely separate, indigenous language families (Kartvelian, Northwest Caucasian, and Northeast Caucasian) thrive, containing dozens of distinct languages. Getting from one valley to the next could be a multi-day trek, allowing each community’s speech to drift in its own direction for centuries, resulting in a bewildering and beautiful linguistic complexity.

We see the same pattern elsewhere:

- New Guinea: The island’s rugged, jungle-clad highlands host the greatest linguistic density on Earth, with over 800 languages spoken among its tribes.

- The Pyrenees: This formidable range separating France and Spain provided a sanctuary for the Basque language, Euskara. It is a true linguistic fossil—a pre-Indo-European isolate, whose relatives have long since vanished from the rest of Europe, swept away by the expansion of Latin and other languages. The mountains were its fortress.

The River Highway: A Conduit of Connection

If mountains divide, rivers unite. Rivers have always been humanity’s first highways, natural arteries for trade, migration, and the flow of ideas. A group living at a river’s mouth is in constant contact with those upstream. This constant interaction has a powerful levelling effect on language.

Along major river systems like the Danube, the Rhine, or the Mekong, we don’t often find sharp linguistic breaks. Instead, we find dialect continua. The speech of one village is only slightly different from the next one downstream, and that one is only slightly different from the one further on. The changes are gradual, like a slow fade. Only at the extreme ends of the river are the dialects mutually unintelligible. The river acts as a social and economic lifeline that keeps the language connected, preventing it from fracturing into entirely separate tongues.

Conversely, ancient Egypt’s civilization was famously called “the gift of the Nile.” The river didn’t just provide water for crops; its predictable, navigable course unified Upper and Lower Egypt, fostering a remarkably stable and uniform language that endured for thousands of years.

The Open Plain and Endless Sea: Forging Language Empires

What happens when there are no barriers at all? Open, traversable landscapes—like steppes, deserts, and oceans—allow for rapid, large-scale expansion. On these geographical superhighways, a single language group with a competitive advantage, be it the horse, the chariot, or the ocean-going canoe, can spread its language over immense distances.

The most significant example is the spread of the Indo-European languages. The “Steppe Hypothesis” suggests that from a homeland in the vast Pontic-Caspian Steppe (modern-day Ukraine and Southern Russia), a group of semi-nomadic people spread out around 6,000 years ago. Their mastery of horse domestication and wheeled carts gave them a mobility advantage, allowing them to expand west into Europe, south into Iran, and east into India, their language splintering and evolving into the vast family that includes English, Spanish, Russian, Hindi, and Persian today.

The sea is the ultimate plain. The Austronesian expansion is an epic tale of maritime voyaging. Beginning in Taiwan around 5,000 years ago, these master seafarers used outrigger canoes to hop from island to island, eventually populating a territory stretching from Madagascar off the coast of Africa to Easter Island in the Eastern Pacific. This is why the languages spoken in the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, and by the Māori of New Zealand are all part of the same linguistic family.

Human Geography: The Gravity of Neighbors and Cities

Geography isn’t just about rocks and water; it’s also about proximity. Who are your neighbors? Do you trade with them, or fight with them? Prolonged contact between speakers of different languages can cause them to start borrowing not just words, but even grammatical structures.

This creates a phenomenon linguists call a Sprachbund (German for “speech union”). The Balkans are a classic example. Over centuries of close contact, Albanian, Greek, Romanian, and Slavic languages like Bulgarian and Macedonian—all from different branches of the Indo-European family tree—have developed shared features, such as a postponed definite article (like saying “man-the” instead of “the man”) and a merged case system. They are unrelated by birth, but have become grammatical cousins through geographical cohabitation.

Finally, cities act as linguistic gravitational centers. They pull in people from surrounding regions, becoming melting pots where dialects mix, new slang is born, and often, a “standard” version of a language is forged and broadcast outwards, influencing the entire nation.

Free at Last?

So, are languages still prisoners of geography in our hyper-connected 21st century? The internet, mass media, and air travel have certainly weakened the bars of the geographical prison. English has leapfrogged over mountains and oceans to become a global lingua franca, a feat unthinkable in a pre-technological age.

Yet, the old rules haven’t vanished. The linguistic map of today is a living document of our past. The concentration of languages in the Caucasus still testifies to the power of its peaks. The unity of the Austronesian family still speaks of a shared seafaring history. While we may no longer be shackled by our terrain in the way our ancestors were, the geographical echoes are everywhere, embedded in our grammar and baked into the very diversity of human speech. Geography set the stage, and we are still playing out its script.