The Grey Plague: An Unstoppable Tide

To understand the fence, you must first understand the foe. In 1859, a Victorian grazier named Thomas Austin imported 24 European wild rabbits to his property near Geelong, Victoria, for a spot of hunting. “The introduction of a few rabbits could do little harm and might provide a touch of home, in addition to a spot of hunting”, he famously remarked. It remains one of history’s greatest understatements.

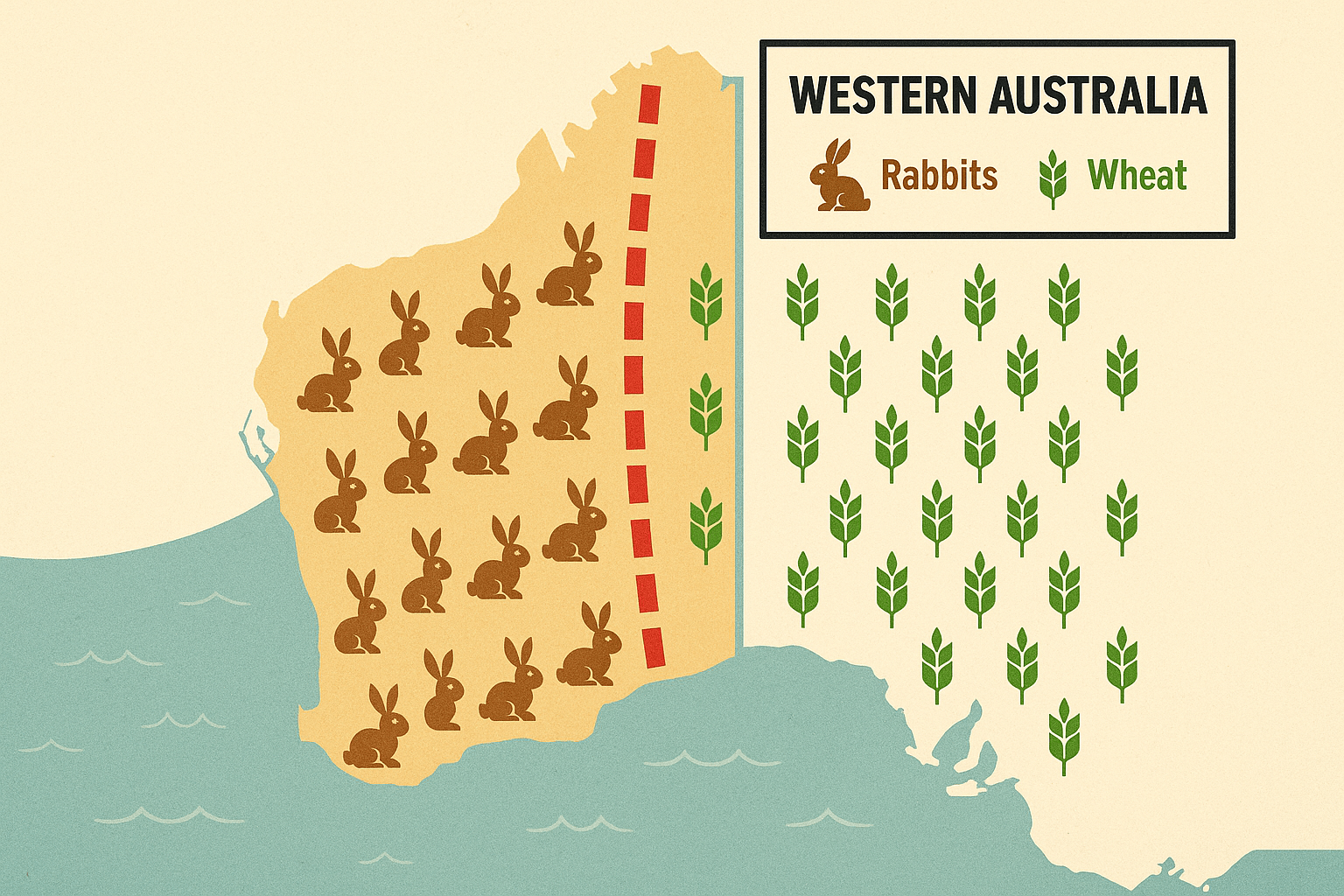

Australia’s physical geography proved to be the perfect incubator for a rabbit explosion. With vast, open grasslands, mild winters, and a critical lack of natural predators like foxes or weasels, the rabbits bred… well, like rabbits. Their population grew exponentially, advancing across the continent at a staggering rate of over 100 kilometres per year. This wasn’t just an inconvenience; it was an ecological and economic catastrophe. The “grey plague” devoured pasture meant for sheep and cattle, stripped vegetation leading to massive soil erosion, and out-competed native wildlife for food and shelter. By the 1890s, this relentless tide of fur was washing towards the agricultural heartlands of Western Australia, threatening to destroy the state’s burgeoning farming economy.

A Line in the Sand: The Grand Plan

Faced with an existential threat, the Western Australian government convened a Royal Commission. The solution they settled on was audacious in its simplicity and staggering in its scale: they would build a fence. Not just any fence, but the longest fence in the world at the time, to quarantine the western third of the continent.

The project, officially called the State Barrier Fence of Western Australia, was ultimately comprised of three interconnected fences:

- No. 1 Fence: The primary barrier, completed in 1907. It stretched an astonishing 1,833 kilometres (1,139 miles) from the southern coast at Starvation Boat Harbour, near Esperance, north to Cape Keraudren, near Port Hedland. It bisected the entire state, crossing arid deserts, salt lakes, rocky escarpments, and dense scrubland.

- No. 2 Fence: Constructed to protect agricultural land further west, it ran for 1,166 kilometres (725 miles), branching off the No. 1 Fence and heading towards the coast near Bremer Bay.

- No. 3 Fence: A smaller, 257-kilometre (160-mile) east-west fence, providing another layer of protection for the southwestern agricultural zone.

In total, the network spanned 3,256 kilometres (2,023 miles). It was a physical manifestation of human geography attempting to impose order on a biological phenomenon, a line on a map made real with sweat and steel.

Building the Barrier: A Monumental Feat of Human Geography

The construction of the Rabbit-Proof Fence, primarily between 1901 and 1907, was a logistical nightmare and a triumph of human endurance. Under the leadership of surveyor Alfred Canning, teams of men ventured into the vast, unmapped wilderness of the Australian outback.

The physical geography they faced was brutal. Workers endured scorching summer heat, freezing desert nights, a lack of fresh water, and utter isolation. Everything had to be hauled overland. Camel trains, uniquely suited to the arid environment, became the lifeblood of the project, carrying tonnes of wire netting, galvanised wire, and supplies. Fence posts were hewn from native timbers like termite-resistant Jarrah and Karri where available; in the treeless plains, metal posts had to be imported and carted hundreds of kilometres.

The construction was relentless. A typical fence-building team consisted of a surveyor, clearers who cut a path through the bush, teamsters managing the camels, and the fence-builders themselves who dug the post holes and strung the wire. They created a barrier designed to be rabbit-proof: the wire mesh was buried several inches underground to prevent burrowing, and the gauge was small enough to stop young rabbits from squeezing through.

A Leaky Barrier: Why the Fence Failed

For all its grandeur and the immense human effort poured into it, the Rabbit-Proof Fence ultimately failed in its primary objective. The rabbits won. The reasons for its failure are a classic lesson in the complexities of invasive species management.

Timing was the fatal flaw. The rabbits were simply too fast. By the time the No. 1 Fence was completed in 1907, significant populations of rabbits had already breached the line. They had moved faster than the men building the fence to stop them. The biological frontier outpaced the construction frontier.

The tyranny of distance and maintenance. A fence over 3,000 kilometres long is only as strong as its weakest point. Maintaining its integrity across such a vast and remote landscape was a near-impossible task. Gates were inevitably left open by farmers and travellers. Other animals, like emus and wombats, dug holes underneath it. Termites devoured the wooden posts, and sandstorms could bury entire sections in a single night.

The nature of the enemy. It only took a few rabbits breaching the fence to establish a new, thriving population on the other side. The fence may have slowed the advance, but it could never truly stop it.

The Enduring Legacy of a Faltering Line

While a failure against rabbits, the fence was not a total loss. Its story morphed, and it found new purpose. It proved to be a reasonably effective barrier against larger, less cunning animals. In 1932, it played a strategic role during the infamous “Emu War”, where soldiers were comically deployed to cull emu populations that were damaging crops, using the fence to funnel the birds.

More importantly, the fence remains relevant today. Much of its length has been adapted and maintained as the modern State Barrier Fence, which now serves primarily as a form of wild dog control, protecting sheep in the agricultural zones from dingoes. It acts as a line of biocontainment, a tool for managing, if not stopping, the movement of animals.

Perhaps its most profound legacy is cultural. The fence was immortalised in Doris Pilkington Garimara’s book, Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence, and the acclaimed 2002 film. It tells the true story of three young Aboriginal girls who, in 1931, escaped from the Moore River Native Settlement and used the fence as a navigational guide on their incredible 1,600-kilometre journey home to Jigalong. For them, this line of division became a pathway to freedom, a powerful symbol of resilience and connection to country that transcends its original purpose.

The Rabbit-Proof Fence stands today as a scar on the Australian landscape—a rusty, weathered monument to a colossal, yet flawed, ambition. It is a powerful reminder that when humanity tries to draw a simple line to solve a complex ecological problem, the geography of the land and the persistence of life often have other plans.