The Unseen Geography of Marine Migration

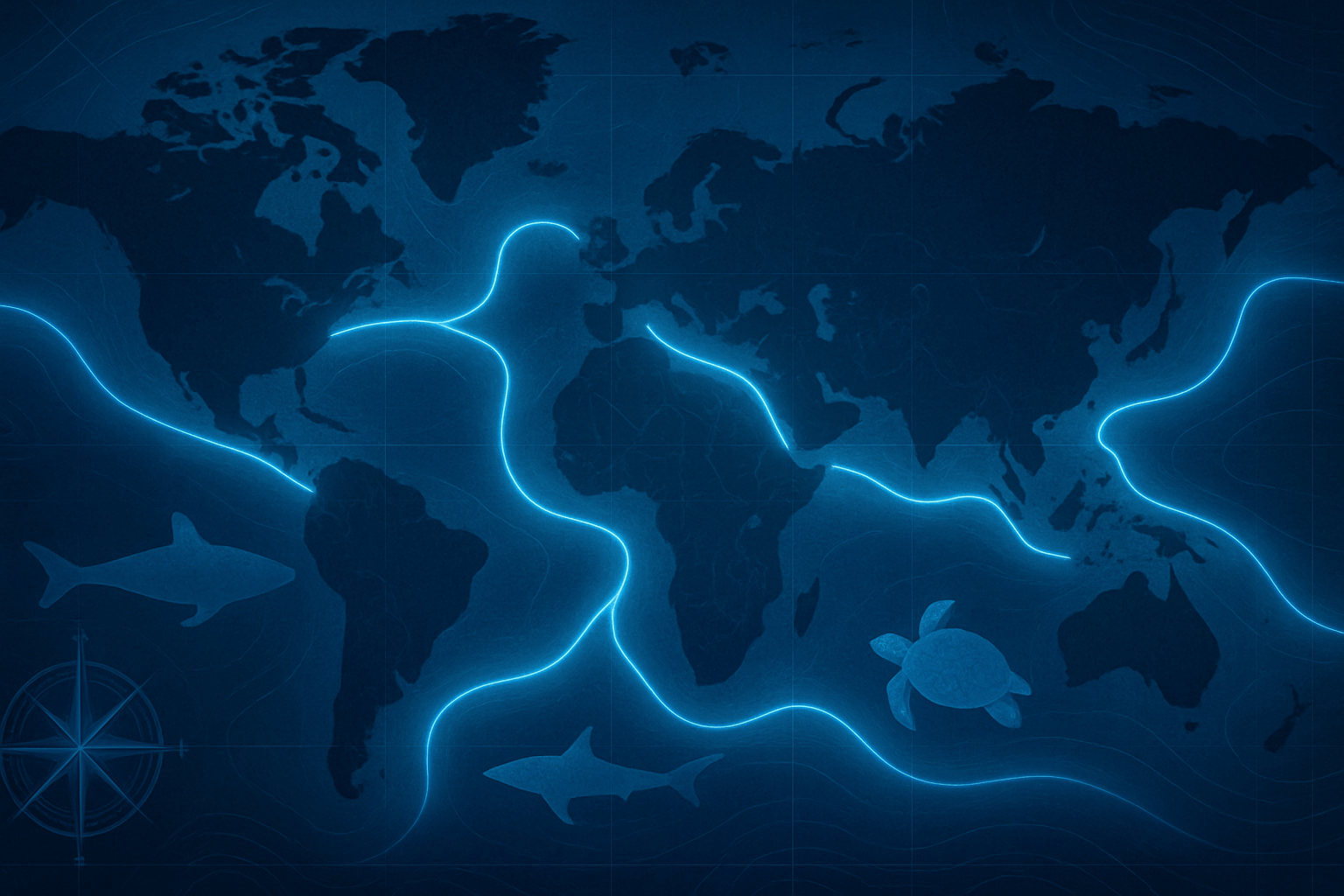

A blue corridor isn’t just a line on a map; it’s a dynamic, three-dimensional space defined by powerful forces of physical geography. Migratory animals like humpback whales, leatherback turtles, and Arctic terns don’t wander aimlessly. They follow predictable routes shaped by the very physics of the ocean.

These routes are often dictated by:

- Ocean Currents: Great ocean currents like the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic or the Kuroshio Current in the Pacific act as massive conveyor belts. Animals ride these currents to conserve precious energy on journeys that can span thousands of kilometers. For example, leatherback turtles follow currents across the entire Pacific, from the shores of Indonesia to the feeding grounds off the coast of California.

- Underwater Topography: The ocean floor is anything but flat. Massive underwater mountain ranges (like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge), isolated volcanic peaks called seamounts, and vast plateaus like the Nazca Ridge off the coast of Peru and Chile serve as critical landmarks. These features create unique ecosystems, causing nutrient-rich water to well up from the depths, forming reliable feeding oases in the open ocean. Whales and sharks use these seamounts as navigational waypoints and vital refueling stops.

- Upwelling Zones: Along the western coasts of continents, such as off Peru, California, and Northwest Africa, prevailing winds push surface water away from the land. This draws cold, nutrient-rich water from the deep ocean to the surface in a process called upwelling. This phenomenon creates some of the most productive marine ecosystems on Earth, supporting massive blooms of plankton that, in turn, feed everything from tiny fish to the largest blue whales. These zones are the bustling “cities” on the migratory map.

A classic example is the epic migration of the humpback whale. Many populations spend their summers feeding in the krill-rich, frigid waters of Antarctica or the Arctic. As winter approaches, they travel towards the equator to warm, sheltered tropical waters—like those around Hawaii, Colombia, or Tonga—to breed and give birth. This pole-to-equator-and-back journey is one of the longest of any mammal, and it relies entirely on this invisible network of currents and feeding grounds.

A Collision Course: Human Geography on the High Seas

The challenge for blue corridors lies where the map of animal migration overlaps with the map of human activity. The same ocean that provides passage for whales is also the bedrock of the global economy, creating a complex and often perilous intersection of human and physical geography.

The Dangers on the Marine Highway

Migrating animals face a gauntlet of human-made threats that are concentrated along their routes:

- Shipping Lanes: Over 90% of global trade travels by sea, creating dense shipping lanes that slice directly through major blue corridors. The waters off the coast of California, the English Channel, and the Strait of Malacca are hotspots for both whale activity and vessel traffic. The result is a high risk of lethal ship strikes. Furthermore, the constant, low-frequency noise from container ships can drown out the sounds whales use to communicate and navigate, causing chronic stress and confusion—imagine trying to navigate a highway with a blindfold and earmuffs.

- Industrial Fishing: Large-scale fishing operations, often concentrated in the same productive upwelling zones that attract marine life, pose a dual threat. Bycatch—the accidental capture of non-target species—kills hundreds of thousands of whales, dolphins, and turtles each year. Even more insidious is “ghost gear”, abandoned or lost fishing nets and lines that drift for decades, entangling and killing countless animals.

- Resource Extraction and Pollution: The search for oil, gas, and minerals is moving further offshore and deeper into the ocean. Seismic surveys for these resources create deafening underwater explosions, while the risk of oil spills and chemical pollution presents a constant threat to any creature passing through.

Charting a New Course: The Geopolitics of Protection

Protecting a forest corridor might involve a few landowners or a single government agency. Protecting a blue corridor that crosses a dozen national jurisdictions and the lawless high seas is a geopolitical puzzle of immense proportions.

Science is the first step. Researchers use sophisticated satellite tags to track individual animals, creating stunningly detailed maps of their movements. This data reveals the precise location and timing of these marine highways. Combined with environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling and acoustic monitoring, we now have a clearer picture than ever of where these critical zones are.

The true challenge is political. A whale migrating from its feeding grounds in Antarctica to its breeding grounds off the coast of Panama will swim through the high seas (waters beyond national jurisdiction) and the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of countries like Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Costa Rica. Protecting that single whale’s journey requires all these nations—and the international bodies that govern shipping and fishing on the high seas—to cooperate.

One landmark initiative is the “MigraVía” or “Whale Superhighway” along the Pacific coast of the Americas. Countries like Ecuador (with its vital Galapagos Marine Reserve), Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia have worked to create protected areas and manage fisheries to safeguard the humpback whale’s path. Another critical area is the Costa Rica Thermal Dome, a unique oceanographic feature that forms seasonally in the Pacific. This dome of warm water pushes nutrient-rich cold water near the surface, creating a massive feeding ground for blue whales. Because it lies partially in the high seas, its protection is a test case for international cooperation.

Hope is on the horizon. The recent adoption of the UN High Seas Treaty (also known as the BBNJ agreement) provides, for the first time, a legal framework to establish marine protected areas in international waters. This could be the key to stitching together disparate national efforts into a truly global network of blue corridors.

Redrawing Our Map of the Ocean

Blue corridors force us to see the ocean not as an empty blue expanse on a map, but as a living, dynamic geography interwoven with life. They represent a fundamental shift in our relationship with the marine world—from a place of pure extraction to a space we must learn to share. Successfully protecting these routes will require more than science; it will demand a new kind of diplomacy, one that recognizes that the health of our oceans, and the magnificent creatures that travel them, is a shared responsibility that transcends all borders.