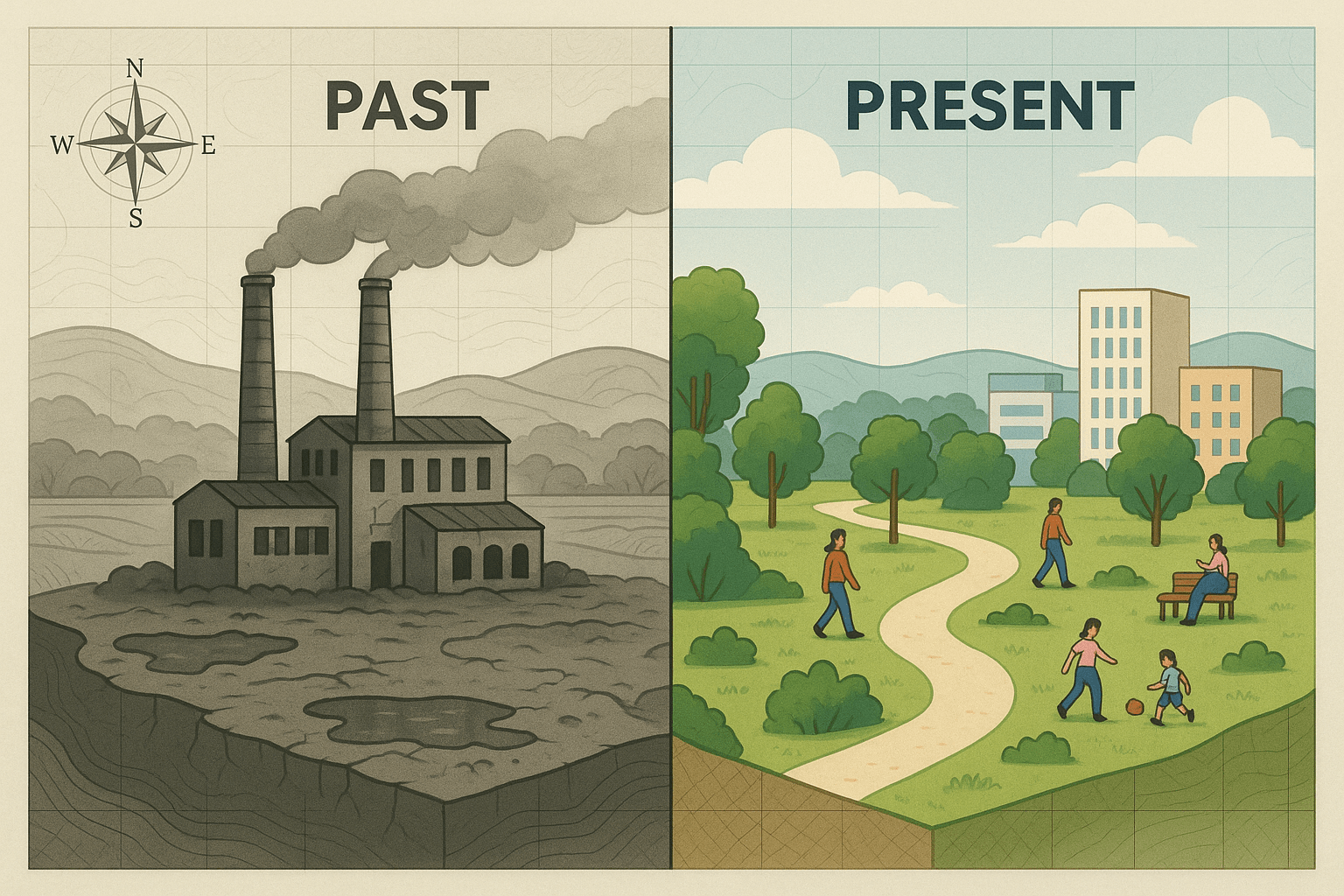

Walk past the chain-link fence of a forgotten factory. You’ll see cracked concrete, colonized by resilient weeds. You’ll see rust-streaked walls and shattered windows staring out like hollow eyes. This is a brownfield site—a scar on the urban map, a ghost of an industrial past. These parcels of land, abandoned and often contaminated from their former lives as mills, railyards, or chemical plants, represent a critical challenge in human geography. But they also hold immense promise. They are the frontier of urban renewal, blank canvases where we can transform post-industrial wasteland into a vibrant community park.

The Geography of Brownfields: Scars on the Urban Map

Brownfields are not random occurrences; their locations tell a story of economic and social geography. They are the physical legacy of deindustrialization, a phenomenon that reshaped cities across the globe from the American Rust Belt to the Ruhr Valley in Germany and the industrial heartlands of the UK.

Historically, heavy industry clustered along key transportation corridors. Factories and mills were built on the banks of rivers and canals for water power and transport, or alongside railways for moving raw materials and finished goods. As these industries declined, they left behind a unique spatial pattern of dereliction. These sites are often found in what were once working-class neighborhoods, creating a profound issue of environmental justice. For decades, residents living near these sites have borne the brunt of the pollution, visual blight, and economic depression left in their wake.

The physical geography of a brownfield is complex and often hazardous. The soil and groundwater can be a toxic cocktail of contaminants left over from their industrial past:

- Heavy metals like lead, arsenic, and chromium from foundries and tanneries.

- Petroleum hydrocarbons from old gas stations or fuel depots.

- Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) from electrical equipment.

- Asbestos from old building insulation.

This hidden, underground geography of contamination is the first and greatest hurdle to overcome in the journey from wasteland to parkland.

The Transformation: A Symphony of Science and Design

Reclaiming a brownfield is a multi-stage process that fuses environmental science with landscape architecture and urban planning. It’s about healing the land before building upon it.

Step 1: Investigation and Assessment

Before any soil is moved, scientists become detectives. They create a detailed map of the site’s environmental conditions. Using ground-penetrating radar and by drilling core samples, they determine the type, concentration, and spatial extent of the contaminants. This phase is crucial for understanding the scale of the problem and designing an effective cleanup strategy.

Step 2: Remediation (The Cleanup)

Remediation is where the physical transformation begins. The chosen method depends on the contaminants, budget, and future use of the site. Common techniques include:

- Excavation: The most straightforward approach is simply digging up the contaminated soil and trucking it to a specialized landfill. While effective, it essentially moves the problem elsewhere.

– Capping: The contaminated area is covered with an impermeable layer (like a thick plastic liner or clay) and then buried under several feet of clean soil. This essentially creates a new, artificial geology on the site, safely sealing the hazards below.

– Bioremediation: A more elegant solution that uses nature to heal itself. Specific microorganisms are introduced to the soil to break down organic contaminants like oil into harmless substances.

– Phytoremediation: This fascinating technique involves planting specific species of plants (like sunflowers, willows, or poplars) that are known to absorb heavy metals and other toxins from the soil into their tissues. The plants are later harvested and safely disposed of.

Step 3: Redevelopment and Reintegration

With the land declared safe, the vision for a park comes to life. This isn’t just about planting grass and trees; it’s about re-weaving the site back into the urban fabric. New pathways connect the park to surrounding neighborhoods, ending decades of isolation. Bioswales and rain gardens are designed to manage stormwater, improving the local hydrology. The new green space creates a “cool island” effect, mitigating urban heat, while also providing a habitat for birds and pollinators, boosting local biodiversity.

Global Success Stories: Mapping a Greener Future

The theory of brownfield renewal is powerful, but the real inspiration lies in the success stories from cities around the world. These projects have not only created beautiful parks but have also redefined their region’s geography and identity.

Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord, Germany

Perhaps the world’s most iconic brownfield transformation, this park is located in Germany’s Ruhr Valley, the heart of its former coal and steel empire. Instead of demolishing a defunct ironworks, the designers chose to celebrate its industrial heritage. A massive gasometer was filled with water to become Europe’s largest indoor diving center. Old ore bunkers were converted into a climbing wall for mountaineers. The towering blast furnace is now an observation deck offering panoramic views. The park brilliantly integrates nature with industrial ruins, creating a unique cultural landscape that draws over a million visitors a year and stands as a symbol of the region’s post-industrial rebirth.

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, London, UK

The site for the 2012 London Olympics was, for a century, one of the city’s most polluted industrial dumping grounds. Located in East London’s Lower Lea Valley, the area was a patchwork of scrapyards, chemical factories, and neglected waterways. The Olympics served as the catalyst for one of the largest brownfield remediation projects in European history. Two million tons of contaminated soil were excavated and cleaned—much of it on-site in special “soil hospitals.” The polluted rivers were cleaned and re-landscaped. Today, the park is a thriving hub of recreation, nature, and community, featuring world-class sports venues, beautiful gardens, restored wetlands, and new residential neighborhoods. It has fundamentally altered the map and perception of East London.

Gas Works Park, Seattle, USA

Perched on the shore of Lake Union with a stunning view of the Seattle skyline, Gas Works Park is a pioneering example of brownfield reclamation. The site of a former coal gasification plant, it was heavily contaminated with toxic sludge. In the 1970s, landscape architect Richard Haag championed a radical vision: preserve the rusting ruins of the plant as industrial sculptures and use bioremediation techniques to clean the soil. A large “earth mound” caps the most toxic areas, creating a popular kite-flying hill. Gas Works Park transformed an industrial eyesore into one of Seattle’s most beloved public spaces and proved that a city’s industrial past could be an aesthetic asset, not something to be erased.

Rewriting the Urban Narrative

Brownfield redevelopment is far more than an environmental cleanup operation. It is an act of geographical healing. It’s a chance to address the historical inequities of industrial pollution, to improve public health, and to combat climate change by increasing urban green space. By looking inward at these forgotten lands, cities can find the space they need to grow more sustainably. Each reclaimed brownfield, whether it becomes a park, a housing development, or a commercial center, is a testament to our ability to rewrite the urban narrative—turning a story of decay and abandonment into one of resilience, community, and hope.