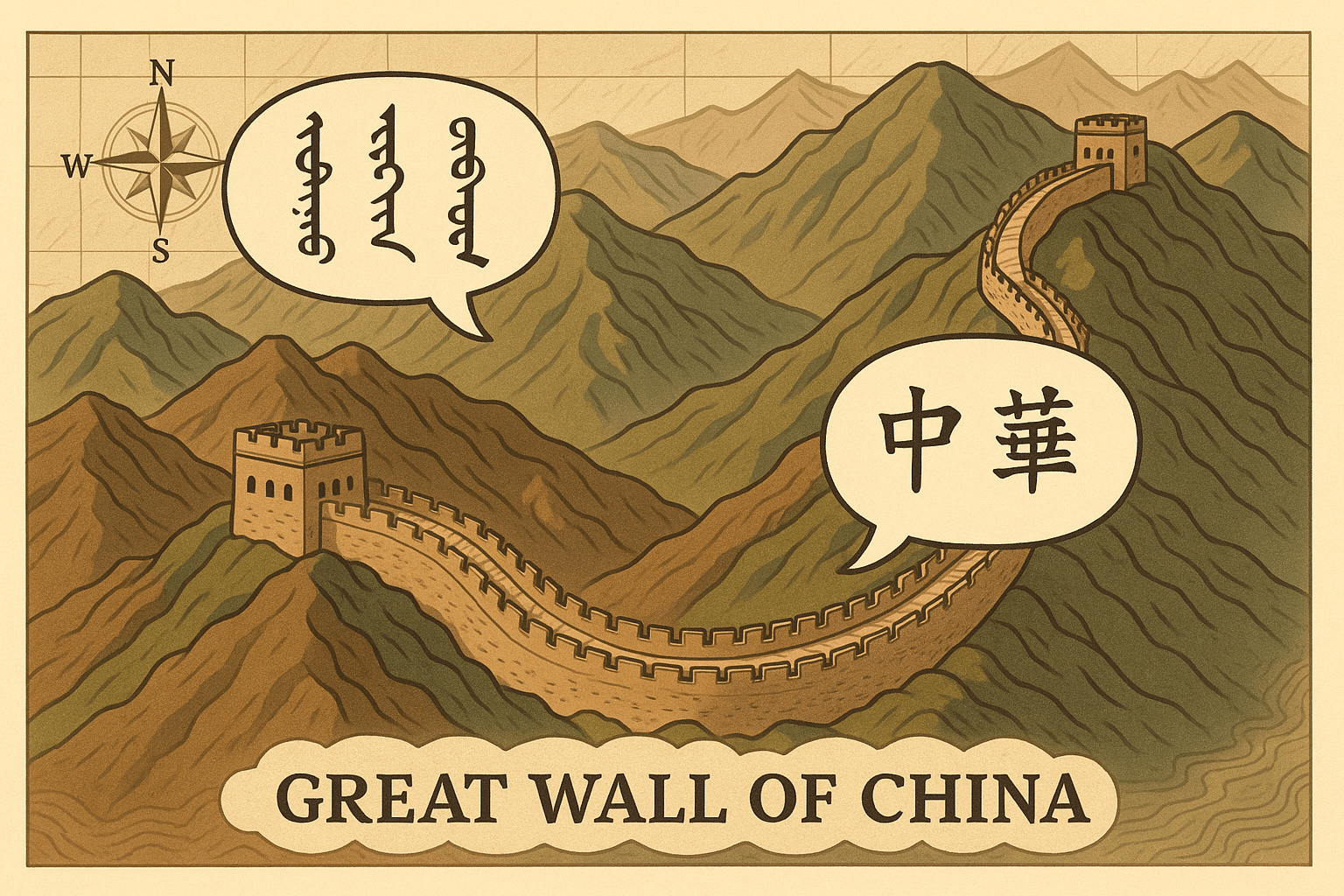

The answer is more complex and fascinating than a simple yes or no. While the Wall itself wasn’t an impermeable linguistic seal, it stands as a powerful symbol of the broader geographical and political forces that carved China’s incredibly diverse linguistic map. To understand its role, we must first look at the landscape it was built upon.

The Great Linguistic Divide: North vs. South

First, it’s crucial to understand that “Chinese” is not one single language. It’s a family of languages, known as the Sinitic languages, which are as different from one another as Spanish is from French or Italian. A Mandarin speaker from Beijing would find the Cantonese spoken in Hong Kong or the Shanghainese spoken in Shanghai almost entirely unintelligible.

The biggest linguistic fault line in China runs roughly east to west, separating the country into two distinct halves: north and south. The north is linguistically quite uniform. From the plains of Manchuria to the highlands of Yunnan, the vast majority of the population speaks dialects of Mandarin (known as Guanhua, or “the speech of officials”). Southern China, in contrast, is a linguistic mosaic. Here you’ll find:

- Wu languages (e.g., Shanghainese)

- Yue languages (e.g., Cantonese)

- Min languages (e.g., Hokkien, Teochew), which are famously diverse even among themselves

- Hakka, Gan, and Xiang languages

So, why is the north so uniform and the south so diverse? The answer lies in geography, and the Great Wall is a key part of that story.

The Wall as a Frontier Marker

The Great Wall wasn’t built in a random location. Its path, especially the well-preserved sections built during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), roughly corresponds to a major natural and agricultural boundary. This boundary is closely related to the famous Qinling-Huaihe Line, an invisible but profoundly important geographical line that splits China climatologically.

North of this line, the climate is colder and drier; the staple crops are wheat and millet. South of it, the climate is warmer and wetter, perfect for cultivating rice. The Great Wall effectively fortified the northern edge of this southern, rice-growing, densely populated Han Chinese heartland.

By defining this frontier, the Wall reinforced a pre-existing cultural and economic divide. This had massive linguistic consequences:

- Homogenization of the North: For much of Chinese history, the political capital was in the north—cities like Xi’an, Luoyang, and most famously, Beijing. These cities were close to the frontier, the nerve centers for defending the Great Wall. The language of the court and the administration, an early form of Mandarin, spread throughout the northern plains via soldiers, officials, and merchants. This vast, relatively flat terrain facilitated communication and allowed the prestige dialect of the capital to level out local linguistic differences, creating the vast Mandarin-speaking zone we see today.

- Isolation of the South: Southern China is a different world geographically. It’s a rugged landscape of mountains, hills, and powerful rivers like the Yangtze and Pearl. While the Great Wall kept northern invaders out, these southern mountains acted as internal barriers. When northern dynasties collapsed, waves of refugees fled south. These groups carried their forms of Chinese with them and settled in isolated pockets, protected by the terrain. Their languages then evolved in relative isolation, preserving older features and developing new ones, leading to the incredible diversity of the south.

More Than a Wall: A Land of Barriers

The Great Wall wasn’t the only barrier at play. The rugged topography of southern China is the real engine of linguistic diversification. The Nanling Mountains, for instance, form a formidable barrier that separates the Cantonese-speaking Pearl River Delta from the rest of China. It’s no surprise that Cantonese is one of the most distinct and well-preserved Sinitic languages.

Similarly, the coastal province of Fujian is almost entirely walled off from the interior by the Wuyi Mountains. This isolation allowed the Min languages to evolve to such an extent that they are considered the most divergent of all Chinese language groups. Some linguists argue that Min languages split off from the Chinese family tree earlier than any other branch. Their isolation, fostered by mountains and the sea, created a unique linguistic incubator.

The Hakka people (literally “guest families”) are a perfect human example of this process. They are believed to be descendants of northern Chinese who migrated south in several waves over a thousand years. Rather than displacing existing populations, they settled in the poorer, hilly regions between Cantonese, Min, and Gan-speaking areas. Their language, Hakka, acts as a sort of linguistic island, preserving features of the Middle Chinese they brought with them while being surrounded by other languages.

Conclusion: A Man-Made Symbol of a Natural Divide

So, was the Great Wall a linguistic barrier? Not directly. A merchant from Beijing and a Mongol trader could still communicate across its gates. Words and ideas could, and did, cross the frontier.

However, the Wall was the physical manifestation of the most important divide in China: the line between the nomadic north and the agricultural south. It was the heavily militarized border of a political and cultural world. By solidifying this frontier, it facilitated the spread of a standardized Mandarin throughout the administrative region it was built to protect—the North China Plain.

Ultimately, the Great Wall’s linguistic influence is symbolic. It represents the northern edge of a geographical reality where southern mountains and rivers did the real work of linguistic division. The Wall held the line in the north, while the mountains to the south created the patchwork of valleys and basins where a hundred linguistic flowers could bloom. It stands as a powerful reminder that the story of a language is often written by the contours of the land itself.