Look at a world map of time zones. At first glance, it seems like a reasonable, if colorful, attempt to divide the globe into neat, 24-hour slices. But look closer. The lines aren’t straight. They zig, they zag, they swerve dramatically to accommodate a single island chain, and sometimes a single, vast country decides to ignore the lines altogether. This isn’t sloppy cartography; it’s a map of power, history, and identity. Time zones, those seemingly objective measures of our day, are one of the most fascinating and overlooked arenas of politics. They are a testament to the fact that on a human map, lines of longitude always bend to lines of power.

The Logical Illusion of Straight Lines

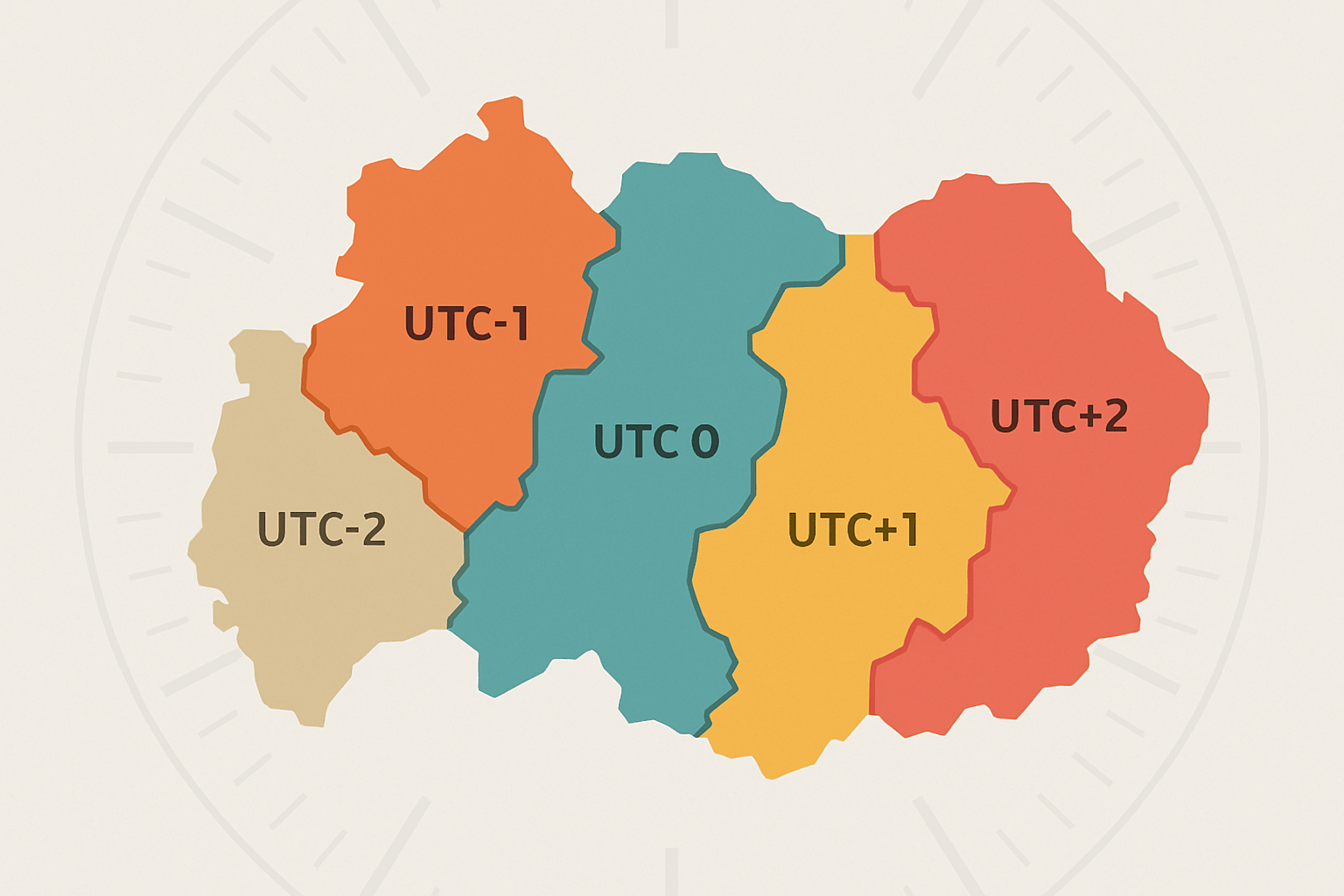

In theory, timekeeping is simple geometry. The Earth spins 360 degrees in 24 hours, meaning it rotates 15 degrees every hour. The logical solution, proposed by Canadian engineer Sir Sandford Fleming in the late 19th century, was to create 24 time zones, each a 15-degree-wide longitudinal wedge. This system of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) brought order to the chaos of a world where every town set its clocks by the local noon sun, a nightmare for the burgeoning railway networks.

But people don’t live in neat longitudinal wedges. We live in countries, provinces, and cities with complex economic and social ties. Almost immediately, the ideal grid of time was warped by reality. The straight lines on the globe became jagged lines on the map for practical reasons:

- National Borders: Most countries prefer to exist within a single time zone for administrative and commercial cohesion. France, despite being geographically smaller than Texas, has the most time zones of any country (12) due to its overseas territories, but mainland France adheres to one.

- Geographical Barriers: A mountain range or a vast desert can make it more practical for a community to align its time with the accessible side, regardless of longitude.

– Economic Regions: Sometimes a region’s economic life is more tied to a neighbor in a different time zone than to its own capital. Time zone boundaries are often drawn to keep metropolitan areas or key trading partners on the same clock.

These practical adjustments make sense. But where time zones get truly fascinating is when they are used not for convenience, but for control and as a statement of national identity.

One Nation, One Time: China’s Political Clock

Perhaps the most dramatic example of time as a political tool is the People’s Republic of China. Geographically, China spans five full time zones, from the coast near Shanghai to the westernmost border with Afghanistan. If you were to travel from one end to the other in the United States, you’d change your watch three times. In China, you don’t change it at all.

Since the Communist Party came to power in 1949, the entire country has officially run on a single time: Beijing Time (UTC+8). This was a deliberate act of centralization, a way to impose unity and state control over a vast and diverse territory. The clock became a symbol of a unified nation, governed from a single capital.

For those living in the eastern part of the country, like Shanghai, the time is a reasonable fit for the sun’s rhythm. But in the far west, in regions like Xinjiang and Tibet, the policy creates a profound disconnect. In Kashgar, a city over 2,000 miles west of the capital, the sun is at its highest point around 3:00 PM Beijing Time. School might officially start at 10:00 AM, when the sun has barely risen. To cope, an informal, local “Xinjiang Time” (UTC+6) exists, running two hours behind the official clock. People live a dual-time existence: their daily lives follow the sun, while government offices, transport, and official business run on the time of a distant capital. It’s a daily reminder of where political power resides.

Living on Borrowed Time: Spain’s Historical Anomaly

If China’s time zone is a statement of unity, Spain’s is a ghost of history. Geographically, Spain and Portugal sit squarely on the same longitude as the United Kingdom and Ireland. They should naturally be in the Greenwich Mean Time zone (UTC+0). Portugal is, but Spain is not.

Instead, Spain runs on Central European Time (CET), the same time as Berlin and Rome, one hour ahead of where it should be. This discrepancy dates back to 1940. As a gesture of solidarity with Nazi Germany, Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco moved the country’s clocks forward an hour. It was meant to be a temporary wartime measure, but after the war, it was never changed back.

This political decision from over 80 years ago has had a lasting impact on Spanish culture. Spaniards live permanently out of sync with the solar day. The sun rises and sets later than it should, which helps explain the country’s famously late meal times and work schedules. That 9:00 PM dinner in Madrid feels less extreme when you realize that, by the sun’s clock, it’s closer to 8:00 PM. There are ongoing debates in Spain to return to “the right time zone”, with proponents arguing it would improve productivity and align lifestyles with natural circadian rhythms. The clock, in Spain, is a living artifact of its 20th-century political history.

Time-Sovereignty: The Ultimate Political Statement

The power to set a nation’s clocks is a potent expression of what some call “time-sovereignty.” It’s a declaration of autonomy, a way to draw a line—not on a map, but on the timeline itself.

Consider these examples:

- North Korea: In 2015, North Korea created its own “Pyongyang Time” (UTC+8:30), breaking from the time zone it shared with South Korea and Japan. The move was explicitly political, intended to erase a remnant of Japanese imperialism. In 2018, as a gesture of peace and reconciliation, North Korea dramatically reverted to South Korea’s time.

- Venezuela: In 2007, President Hugo Chávez created a unique half-hour time zone (UTC-4:30), claiming it allowed for a “fairer distribution of the sunrise” among his people. The move was reversed in 2016 by his successor to help alleviate a national energy crisis.

- Crimea: Following its annexation by Russia in 2014, the Crimean peninsula was ordered to jump its clocks forward two hours to align with Moscow Time (UTC+3). The change was an immediate and unambiguous symbol of its new political reality.

These decisions have little to do with the sun and everything to do with politics. They use time to signal allegiance, declare independence, or defy enemies. Even the International Date Line, that seemingly absolute boundary between one day and the next, was bent by politics. In 1995, the Pacific nation of Kiribati shifted the line eastward in a massive loop to ensure all its islands, which straddled the line, were on the same day. The move wasn’t about defiance but practicality—ending the logistical nightmare of having one half of the country be a full day ahead of the other.

From the vast, unified clock of China to the tiny, time-divided island of Märket between Finland and Sweden, the world’s time zone map is a messy, beautiful, and deeply human document. It shows us that the way we measure our days is as much a product of our politics, our history, and our identity as it is the Earth’s steady rotation. The next time you change your watch when traveling, remember you’re not just adjusting to a new schedule—you’re participating in a global story of clockwork politics.