Think about your favorite coffee shop. Now, think about how you get there from your home. You probably don’t pull out a paper map or even type the address into your phone. You just… go. You know the turns to make, the big intersection to cross, and the oddly-painted building you pass just before you arrive. You are navigating using a remarkable piece of neural technology: a cognitive map.

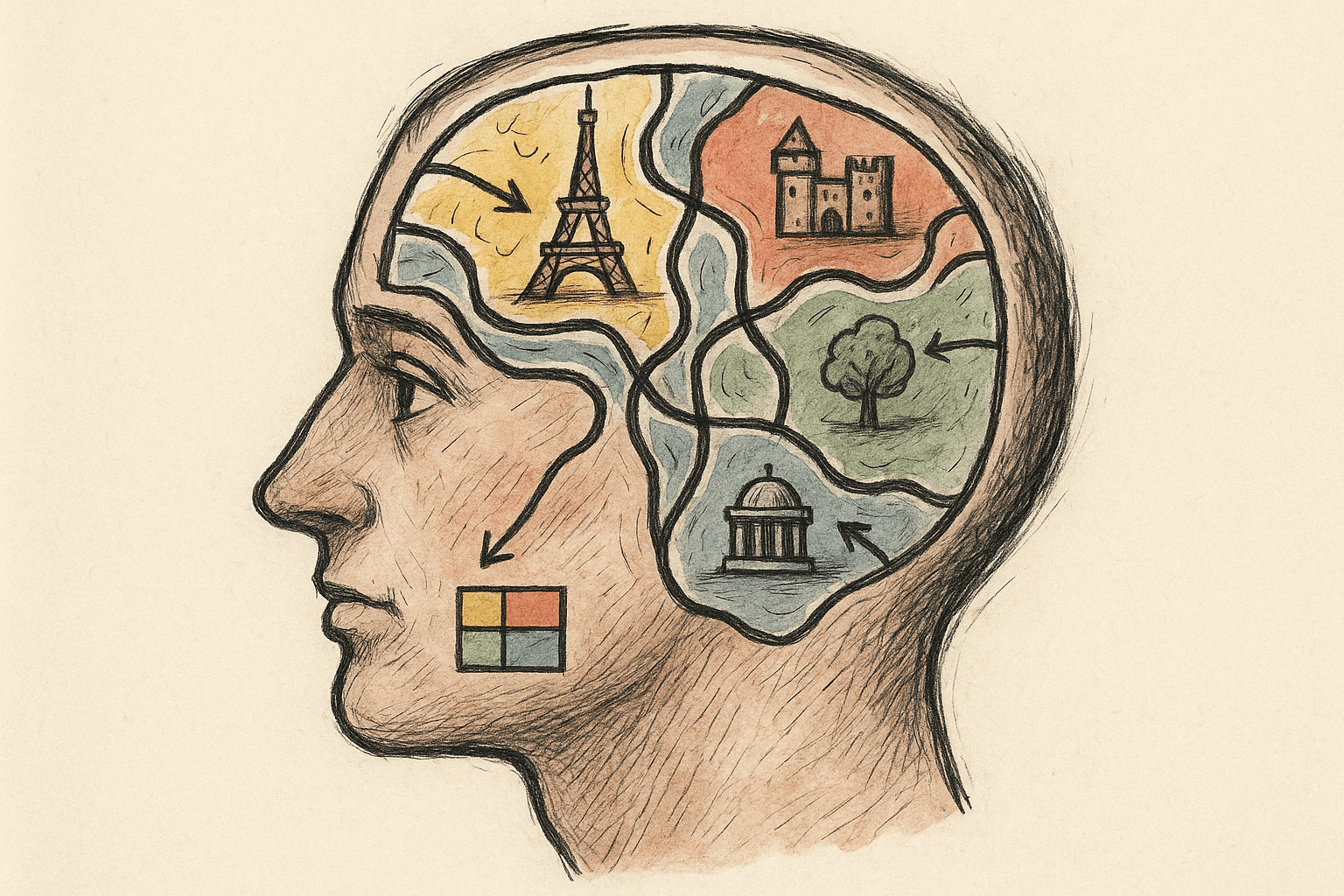

Far from a simple list of turn-by-turn directions, a cognitive map is a rich, dynamic mental representation of a spatial environment. It’s the personal atlas you build inside your head for your home, your neighborhood, your city, and even the world. This internal GPS is a cornerstone of human geography, shaping how we perceive, interact with, and feel about the places we inhabit.

The Brain’s First Draft: How We Build Our Maps

The concept isn’t new. In the 1940s, psychologist Edward Tolman observed rats in mazes. He noticed that rats that had explored a maze could find the cheese even when the familiar route was blocked. They didn’t just learn a sequence of right and left turns; they had formed a mental overview of the maze’s layout. Tolman called this a “cognitive map.”

Humans do the same thing, but on a much grander scale. In his seminal 1960 book, “The Image of the City”, urban planner Kevin Lynch identified five key elements that we use to structure our mental maps of cities. These are the building blocks of our internal geography:

- Landmarks: These are the anchor points. They are easily identifiable objects that serve as external reference points, like a tall skyscraper, a famous statue, a unique bridge, or a prominent mountain. The Eiffel Tower in Paris or the Space Needle in Seattle are city-scale landmarks, but it could also be the large oak tree in your local park.

- Paths: These are the channels along which we move. Streets, sidewalks, trails, canals, and transit lines are all paths. We connect our landmarks using paths, forming the circulatory system of our mental city.

- Districts: These are medium-to-large sections of a city that we conceive of as having a common, identifying character. Think of a city’s “Financial District”, “Theatre District”, or a historic “Old Town.” You know when you’ve entered one, and you know when you’ve left.

- Edges: These are the boundaries between two areas. They can be physical barriers like rivers, walls, and major highways, or they can be more subtle, like the seam where a residential area meets a commercial one. Edges help us compartmentalize our city into manageable districts.

- Nodes: These are strategic focus points, like major intersections, town squares, or busy subway stations. They are the junctions of paths, the heart of a district, and often contain landmarks. Times Square in New York or Piccadilly Circus in London are classic examples.

When you first move to a new city, you start by learning a few key paths (the route to work, the way to the grocery store) and identifying a couple of landmarks. Over time, as you explore more, these disparate pieces begin to connect, forming districts and nodes, until a coherent, flexible map emerges.

From A-to-B to a Bird’s-Eye View

Not all cognitive maps are created equal. Geographers and psychologists distinguish between two types of spatial knowledge.

First comes route knowledge. This is a basic, ground-level understanding based on a sequence of actions. For example: “To get to the library, I walk out my door, turn left, walk to the big intersection, turn right at the pharmacy, and it’s two blocks down on my left.” It’s linear and egocentric—based entirely on your own movement through the space. You know how to get from A to B, but you might not know how B relates to a different point, C.

With more experience, you can develop survey knowledge. This is a more holistic, map-like understanding—a “bird’s-eye view.” You understand the spatial relationships between different locations, even if you haven’t traveled the direct path between them. You can take shortcuts, find novel routes, and point in the direction of a landmark from anywhere in the city. This is the mark of a truly developed cognitive map.

Why Is My Friend a Human Compass (And I’m Not)?

We all know someone with an uncanny “sense of direction.” They can be dropped in a new neighborhood and instinctively know which way is north. Meanwhile, others get lost in a shopping mall. What accounts for this difference?

The answer is a mix of biology, experience, and strategy.

A key brain region for spatial memory is the hippocampus. A famous study of London taxi drivers revealed that, after years of navigating the city’s complex, 25,000-street layout to pass “The Knowledge” test, they had a significantly larger posterior hippocampus than control groups. This part of their brain had physically grown to accommodate their vast mental map.

But it’s not all genetics. Experience and practice are crucial. The more you actively navigate an environment—paying attention to your surroundings rather than passively following a blue dot on a screen—the stronger your cognitive map becomes. Over-reliance on GPS can short-circuit this process. When your phone tells you “turn left in 200 feet”, you aren’t engaging with landmarks or paths; you’re just following commands. This can prevent the transition from simple route knowledge to robust survey knowledge.

Finally, it comes down to attention. People with a good sense of direction are often paying more attention to spatial cues: the position of the sun, the names of streets, the unique architecture of a building, or the flow of traffic. They are actively gathering data to build and update their mental atlas.

Your Brain, The Cartographer

The concept of a cognitive map extends far beyond your city limits. We have a cognitive map of our country, often distorted by where we live and where we travel. We also have a cognitive map of the world, heavily influenced by media coverage and cartographic conventions like the Mercator projection, which famously enlarges landmasses near the poles (making Greenland look the size of Africa, when it’s actually 14 times smaller).

These internal maps are not perfect replicas of reality. They are personal, functional, and deeply tied to our experiences. They are a beautiful testament to the brain’s ability to make sense of the world, transforming chaotic geographic space into a meaningful, navigable place.

So next time you’re on a familiar journey, put your phone away. Try to “see” the map in your head. Notice the landmarks, trace the paths, and feel the edges of the districts you pass through. You’re not just going somewhere; you’re engaging in the ancient and incredible human art of cartography, with your own brain as the mapmaker.