The Geography of a Fading Frontier

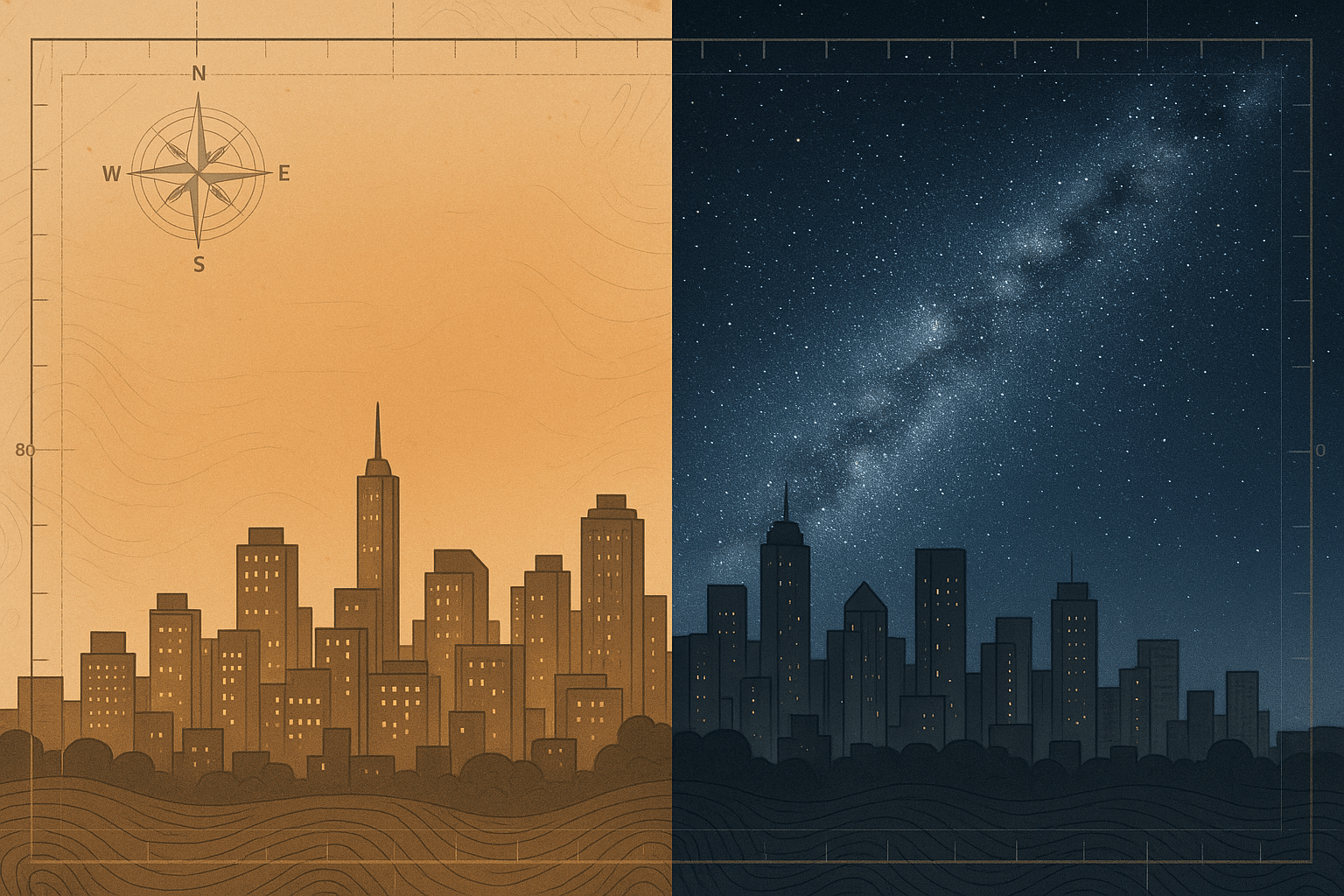

Look up. If you live in or near a city, what do you see tonight? A handful of the brightest stars, perhaps a planet, the hazy orange glow of urban life reflecting off the clouds? For more than 80% of the world’s population, and a staggering 99% in Europe and North America, this washed-out view is the new normal. The river of the Milky Way, a sight that has inspired poets, guided navigators, and defined humanity’s place in the cosmos for millennia, has been erased by a modern phenomenon: light pollution.

Light pollution is more than just an astronomer’s frustration; it is a profound geographical issue. It is the physical manifestation of our 24/7 human footprint, a form of pollution that redraws the map of the natural world. But as the urban glow spreads, a counter-movement is taking root. In the planet’s last pockets of profound darkness, a new kind of park is being designated: the International Dark Sky Preserve. These are not just parks; they are geographical arks, preserving the natural heritage of the night.

Mapping the Glow: The Human Geography of Light Pollution

To understand Dark Sky Preserves, we must first understand the geography of what they are fighting. Light pollution is the excessive, misdirected, or obtrusive use of artificial light. Satellite images of Earth at night tell a powerful story of human geography. The brightest clusters are not random; they perfectly map our planet’s densest urban centers, major transportation corridors, and industrial zones. The Nile Delta is a ribbon of light tracing the river’s path. The eastern United States, Western Europe, and Japan are vast, interconnected constellations of human activity.

This glow is a direct consequence of population density, economic development, and cultural practices. It spills from poorly shielded streetlights, unsecured commercial floodlights, and ever-brighter decorative lighting. This “sky glow” can travel hundreds of kilometers from its source, creating vast domes of light pollution over otherwise dark rural landscapes, fundamentally altering the environment far beyond city limits.

Sanctuaries of Starlight: A World Tour of Dark Sky Preserves

A Dark Sky Preserve, as certified by the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), is a protected area of land possessing an exceptional quality of starry nights and a nocturnal environment. The creation of a preserve is a feat of both physical and human geography, requiring not only pristine skies but also a dedicated community committed to protecting them.

Aoraki Mackenzie, New Zealand

Nestled in the Mackenzie Basin of the South Island, this Gold-Rated reserve is a prime example of ideal physical geography. Surrounded by the towering Southern Alps, the region is shielded from distant city lights. Its high altitude and dry, stable air, a result of the mountain rain shadow effect, provide exceptionally clear viewing conditions. The landscape, defined by turquoise glacial lakes like Tekapo and Pukaki, reflects the brilliant southern sky, which includes the Magellanic Clouds—two satellite galaxies invisible from most of the Northern Hemisphere.

Atacama Desert, Chile

Perhaps the ultimate dark sky destination, the Atacama is one of the driest places on Earth. This hyper-arid environment, coupled with its high-altitude plateau in the Andes, means there is virtually no water vapor in the atmosphere to scatter light or blur images. This unique physical geography has made it the world capital of astronomy, hosting powerful observatories like the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). The dark sky here is not just a treasure; it’s a critical resource for scientific discovery.

Westhavelland, Germany

Proving that pristine darkness isn’t exclusive to remote deserts or mountain peaks, Westhavelland Nature Park is located just 70 kilometers west of Berlin. Its geography is one of lowland wetlands and shallow lakes, making it one of the darkest places in a light-saturated country. Its designation as a Dark Sky Reserve is a triumph of human geography—a testament to rigorous lighting ordinances and community education in a densely populated region. It shows that reclaiming the night is possible even on the doorstep of a major metropolis.

NamibRand Nature Reserve, Namibia

Africa’s first Gold-Rated Dark Sky Reserve, NamibRand encompasses a vast tract of the Namib Desert. Its protection comes from its sheer scale and isolation. The geography is one of endless red dunes and gravel plains under one of the darkest skies ever measured. The reserve operates on a principle of low-impact ecotourism, where the protection of the nocturnal environment is as important as the protection of the iconic desert wildlife like the oryx and springbok.

An Atlas of Impact: Why Darkness is a Vital Resource

The fight for darkness is a fight for ecological and cultural survival. From a physical geography perspective, the day/night cycle is one of Earth’s most fundamental rhythms.

- Ecological Disruption: Artificial light at night disrupts the migratory patterns of birds, which navigate by moonlight and starlight. It disorients newly hatched sea turtles, drawing them toward city lights instead of the safety of the ocean. It impacts nocturnal pollinators like moths and bats, with cascading effects on entire ecosystems.

- Cultural Erasure: From a human geography perspective, losing the stars means losing a core piece of our shared heritage. For millennia, the constellations were our maps, calendars, and storybooks. Polynesian navigators read the star paths to cross the vast Pacific. Ancient farmers planted crops by the rising of certain stars. To lose the night sky is to sever a connection with the science and stories of our ancestors.

The Front Lines of the Fight: Reclaiming the Night in Our Cities

While remote preserves are crucial, the battle against light pollution must also be fought on its home turf: our towns and cities. This is where the geography of policy and planning comes in. The IDA also recognizes “Dark Sky Communities”, which are cities and towns that have adopted and enforced strict, smart lighting ordinances.

Flagstaff, Arizona, is a world leader in this movement. Home to the Lowell Observatory (where Pluto was discovered), the city recognized the value of its dark sky early on. It implemented the world’s first outdoor lighting ordinance in 1958. Today, its policies are a model for urban light management, requiring fully shielded fixtures that direct light downward, using warmer-toned LED lights that are less disruptive to wildlife, and promoting the use of timers and motion sensors.

These efforts are not about turning off all the lights; they are about lighting smarter. By preventing light from trespassing uselessly into the sky, communities can improve safety, save energy and money, and restore a piece of the natural night, one streetlight at a time.

The geography of darkness is shifting. For decades, it was a story of retreat, of light relentlessly conquering the night. But now, through the concerted efforts of scientists, conservationists, and everyday citizens, a new map is being drawn—one that charts a path back to the stars.