We often hear the term “food desert” to describe urban neighborhoods where fresh, affordable food is scarce. It’s a powerful image, painting a map of hunger and inequality within our own cities. But this map only shows one part of the story—the symptom of a much deeper issue. To truly understand the global struggle over what we eat, we need to look beyond the desert and explore the complex, geopolitical landscape of our food systems. This is the terrain where two powerful concepts clash: Food Security and Food Sovereignty.

What is Food Security? The Top-Down Approach

At its most basic, food security, as defined by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food. It’s a framework built on four pillars:

- Availability: Is there enough food produced, either locally or through imports?

- Access: Can people obtain and afford the food that is available?

- Utilization: Do people have the knowledge and sanitation to make good use of the food for a nutritious diet?

- Stability: Is access to food reliable over time, not disrupted by shocks like price spikes or climate events?

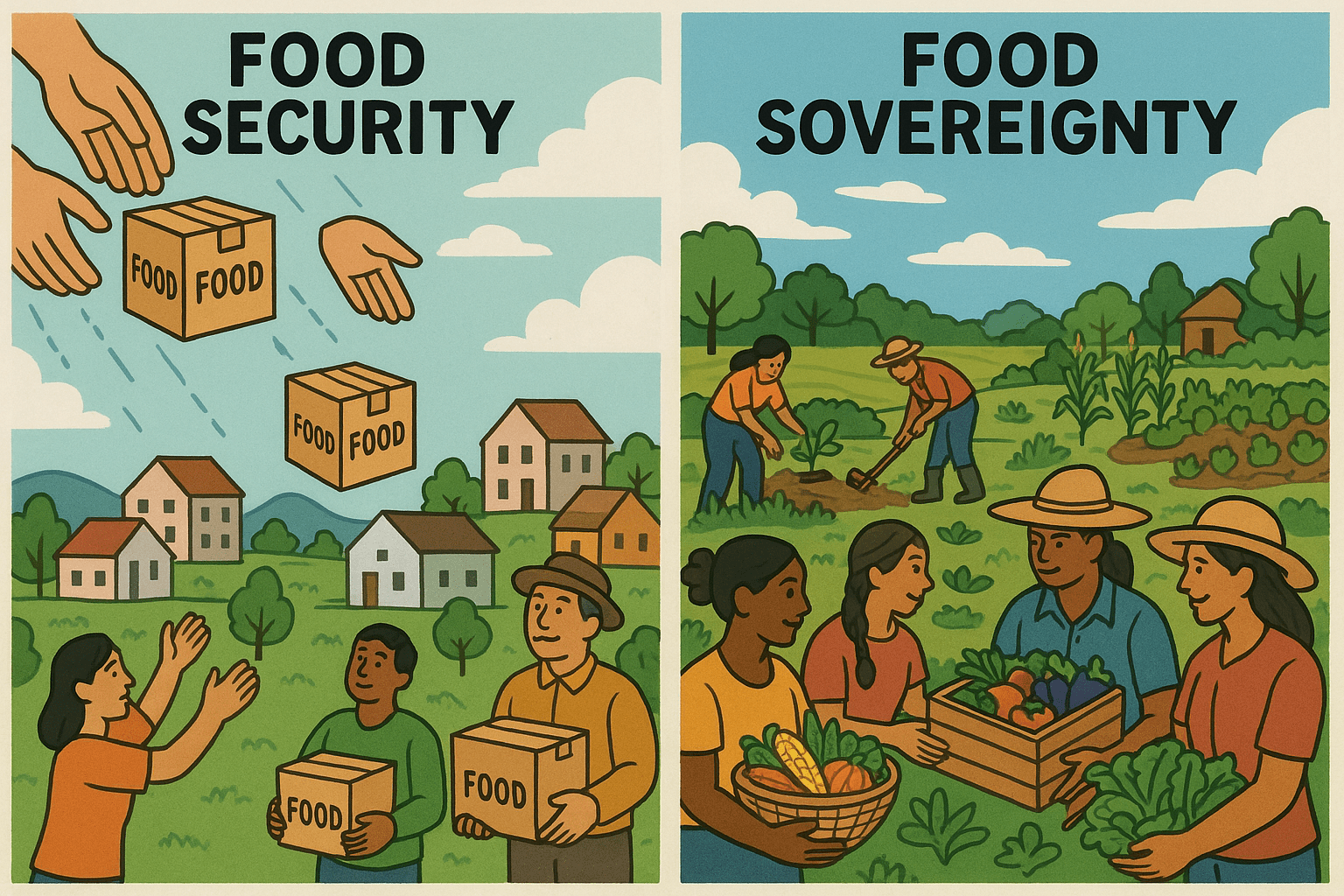

Food security is fundamentally a technical and logistical goal. It’s a top-down model that asks, “How can we, through global markets, international aid, and industrial agriculture, ensure everyone has enough calories?” The geography of food security is one of massive container ships crossing oceans, vast monoculture fields stretching across the American Midwest, and international aid programs distributing grain in drought-stricken regions of the Horn of Africa. The Green Revolution of the mid-20th century is a classic example. By introducing high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, pesticides, and fertilizers to countries like Mexico and India, it dramatically increased food production (availability) and was credited with saving over a billion people from starvation. The goal was noble and, by its own metrics, often successful. But it came at a cost, creating dependency on foreign corporations for seeds and chemicals and often overlooking local ecosystems and farming traditions.

Enter Food Sovereignty: A Declaration of Independence

If food security is about ensuring people are fed, food sovereignty is about asking who decides what they’re fed, how it’s grown, and who controls the system.

Coined in 1996 by the global peasant movement La Vía Campesina, food sovereignty is defined as the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems. It’s not a technical problem; it’s a political right. It seeks to shift power from multinational corporations and distant governments to the people who produce, distribute, and consume the food.

Food sovereignty is a grassroots, bottom-up framework that prioritizes:

- Local Food Systems: It puts local farmers, fishers, and indigenous peoples at the center of the food system, valuing their knowledge and their contribution to the local economy.

- Democratic Control: It calls for communities to have a direct say in food policy, from land use to trade agreements.

- Agroecology: It champions farming practices that work with nature, rather than against it, promoting biodiversity and soil health.

The core difference is one of agency. Food security can be achieved by handing someone a plate of imported rice. Food sovereignty is when that person’s community has the land, seeds, water, and political power to grow their own traditional rice, sell the surplus in a local market, and preserve the ecosystem for the next generation.

Mapping the Struggle: From Global South to American Cities

The fight for food sovereignty is redrawing maps of power and resistance all over the world. This isn’t an abstract debate; it’s a physical struggle over land, water, and seeds.

La Vía Campesina and the Global Stage

Originating in Latin America, La Vía Campesina (“The Peasant Way”) is a coalition of over 200 million farmers, landless workers, and indigenous peoples across 81 countries. Their geography is transnational. They organize protests at World Trade Organization (WTO) meetings, arguing that international free trade agreements often flood their local markets with cheap, subsidized food from the US and Europe, bankrupting small farmers. For them, food sovereignty is a direct challenge to the neoliberal globalization that underpins the dominant food security model.

Indigenous Sovereignty in North America

For Indigenous communities, food sovereignty is inseparable from cultural survival and land rights. In the Great Lakes region of the US and Canada, Anishinaabe communities are working to restore traditional wild rice (manoomin) beds, which are threatened by industrial pollution and development. This is about more than just a food source; it’s about reclaiming spiritual practices, traditional ecological knowledge, and asserting treaty rights over ancestral waters. The map of food sovereignty here is not one of farms, but of lakes, rivers, and forests—a living geography tied to identity.

Urban Agriculture in Detroit, USA

The struggle also unfolds within cities. Detroit, Michigan, is a powerful example. Following the collapse of the auto industry, the city became a textbook case of urban decay, with a shrinking population and tens of thousands of vacant lots. Supermarkets fled the city’s core, creating vast “food deserts.” But from this landscape of neglect, a powerful food sovereignty movement emerged. Organizations like the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network established D-Town Farm on a multi-acre site inside the city. They aren’t just growing vegetables; they are building community power, creating jobs, and providing fresh, healthy food in a city where Black residents have historically been denied it. They are transforming the human geography of a post-industrial city, turning vacant lots—symbols of economic failure—into vibrant centers of food production and community resilience.

Security or Sovereignty: Why the Difference Matters

While food security is a crucial starting point, it can sometimes mask the power imbalances that create hunger in the first place. A nation can be technically “food secure” through massive imports while its own farmers go out of business and its traditional cuisine disappears. Food sovereignty argues that this is not true security. Real security is resilience, and resilience comes from local control, ecological diversity, and social justice.

Looking at the world through the lens of food sovereignty changes our perspective. We see that a community garden is more than a hobby; it’s a political act. We see that saving heirloom seeds is more than nostalgia; it’s a defense against corporate consolidation. It shows us that the geography of our food system is, and always has been, a geography of power. The crucial question is: who gets to draw the map?