Imagine walking through a bustling market, not in search of fruits or spices, but for carefully prepared blocks of earth. For millions of people across the globe, this isn’t a strange fantasy; it’s a deeply ingrained cultural practice. This behavior, known as geophagy, is the deliberate consumption of soil, clay, or other earthen materials. Far from being a random or bizarre craving, geophagy is a complex phenomenon woven into the very fabric of human and physical geography, revealing a profound and ancient relationship between people and the land beneath their feet.

A Practice Etched onto the World Map

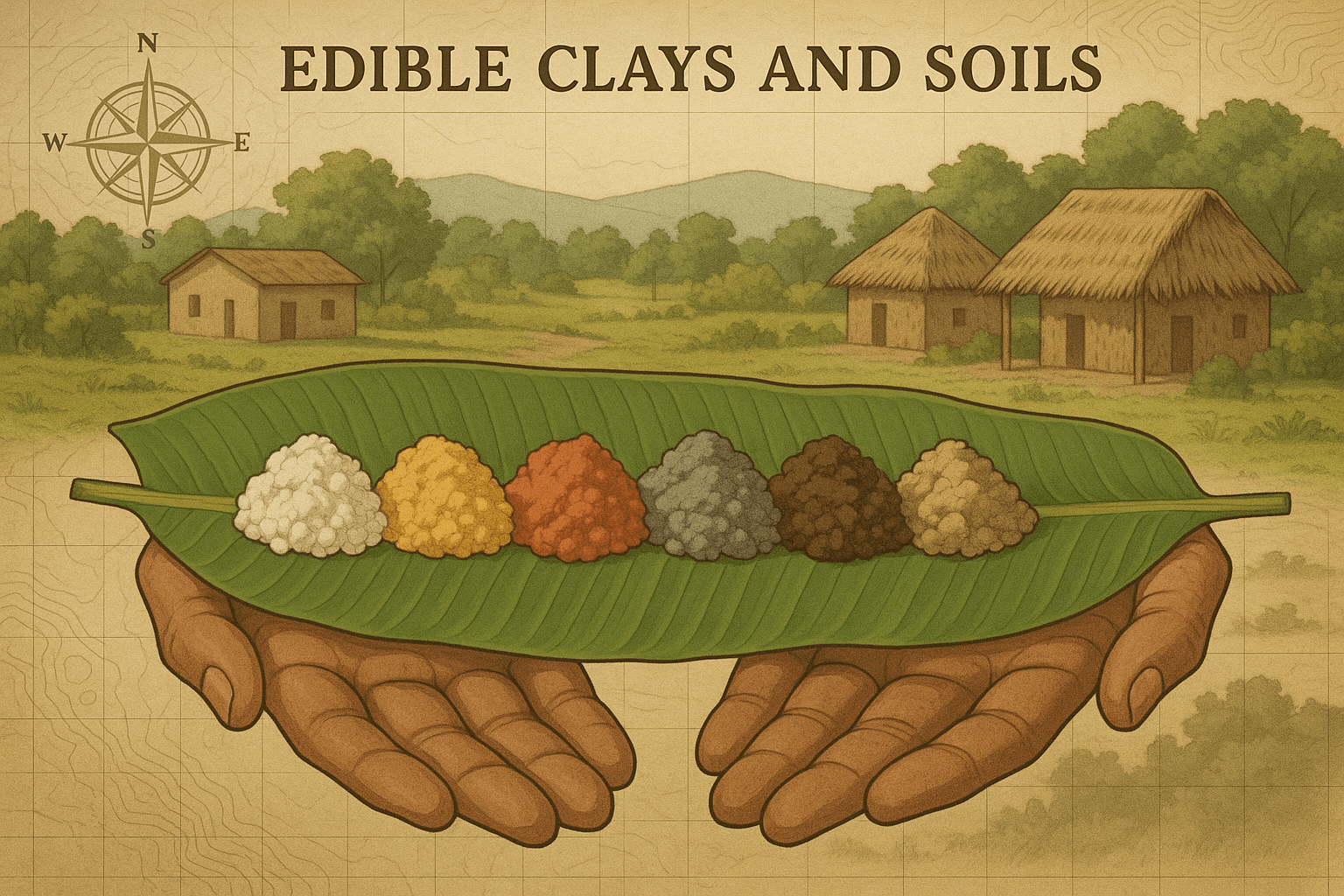

Geophagy is not confined to one remote corner of the world. Instead, its map spans continents, climates, and cultures, with distinct epicenters where the practice is most vibrant. The geographical distribution tells a story of migration, tradition, and the unique properties of local soils.

The African Epicenter

Sub-Saharan Africa is undeniably the global heartland of contemporary geophagy. Here, it is an open, celebrated, and commercialized practice. In the markets of Accra, Ghana, you can find vendors selling smoked or baked clay balls known as ayilo. In Nigeria, pregnant women and others seek out nzu or calabash chalk, a white clay often pressed into ornamental discs. Further south and east, in countries like Kenya, Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, clays sourced from termite mounds are particularly prized, believed to be enriched by the termites’ saliva.

The practice is so common that specific types of clay are named, prepared, and marketed with the same care as any other foodstuff. This geographical concentration points to a tradition that has been passed down through countless generations, becoming an integral part of community life and women’s health in particular.

Across the Atlantic: The Americas

The geography of geophagy in the Americas is a direct echo of the transatlantic slave trade. Enslaved Africans carried the practice with them, and it took root in the clay-rich soils of their new, forced homes. The most prominent example is found in the American South, particularly in Georgia and Mississippi. Here, the consumption of kaolin, a fine white clay, became common. The city of Sandersville, Georgia, is even known as the “Kaolin Capital of the World” due to its vast deposits. While the practice has declined, it persists in some rural communities, a living legacy of African heritage adapting to a new landscape.

Further south, in Haiti, geophagy takes the form of “bonbon tè”—literally, “earth cookies.” Clay is mixed with salt and vegetable shortening, flattened into discs, and dried in the sun. Though often cited as a symptom of extreme poverty, it also holds cultural significance, especially for pregnant women. In the Amazon Basin, indigenous groups have long used clay to detoxify their food, mixing it with bitter, semi-poisonous wild potatoes to make them safe for consumption.

Pockets in Asia and a Historical Echo in Europe

While less widespread, geophagy is also found across Asia. In parts of Indonesia, a baked clay snack called ampo is consumed. In Iran and India, various clays are used in traditional medicine and are sometimes consumed by pregnant women to alleviate morning sickness. Historically, Europe also had its own version. The ancient Greeks prized “Lemnian Earth”, a medicinal red clay from the island of Lemnos, which was formed into tablets, stamped, and sold as a remedy for poison and stomach ailments until the 19th century.

Unearthing the “Why”: Culture, Craving, and Chemistry

Why do people eat earth? The answer lies at the intersection of human geography (culture and tradition) and physical geography (the chemical properties of the soil itself). There isn’t a single explanation, but rather a combination of powerful motivators.

- The Protective Hypothesis: This is one of the strongest scientific theories. Clay particles have an incredible ability to bind to harmful substances. Like a natural filter for the digestive system, consuming clay can protect the stomach from toxins, parasites, and pathogens. This explains why Amazonian parrots and other animals eat clay after consuming toxic fruits, and why humans might have instinctively adopted the same strategy.

- The Nutritional Hypothesis: This theory suggests geophagy is a response to micronutrient deficiencies. Certain clays are rich in essential minerals like iron, calcium, and zinc. For individuals with nutrient-poor diets, especially pregnant or anemic women, clay could act as a natural supplement. The science here is debated—the bioavailability of these minerals can be low—but the overwhelming global link between geophagy and pregnancy suggests a powerful biological drive is at play.

- The Cultural and Soothing Hypothesis: Beyond pure biology, geophagy is a comfort. It’s a tradition, a taste of home, and a practice passed down from mother to daughter. Many women report that it soothes the stomach, acting as a natural antacid to relieve nausea and morning sickness. This combination of physical relief and cultural affirmation makes it a resilient and cherished practice.

From the Ground to the Global Market

Geophagy is not just a historical or rural phenomenon; it has adapted to the modern, globalized world. The demand for specific types of clays has created local and international economies. Miners, often women, excavate the clay from specific sites known for their quality. It is then cleaned, processed, shaped, and transported to urban markets.

Today, the internet has expanded this map even further. Online retailers on platforms like Etsy and Amazon sell calabash chalk from Ghana, kaolin from Georgia, and other earthen clays to diaspora communities around the world. A woman in London or New York with a craving for the ayilo of her youth can now have it shipped to her door. This digital marketplace keeps the tradition alive, connecting people to the specific taste and texture of their ancestral geography, no matter where they are.

Geophagy is a powerful reminder that our connection to the environment is not just about what we build upon it, but sometimes, what we consume from it. It challenges our modern, sanitized view of food and invites us to look at the ground beneath our feet not as mere dirt, but as a source of medicine, culture, and connection that has sustained communities for millennia.