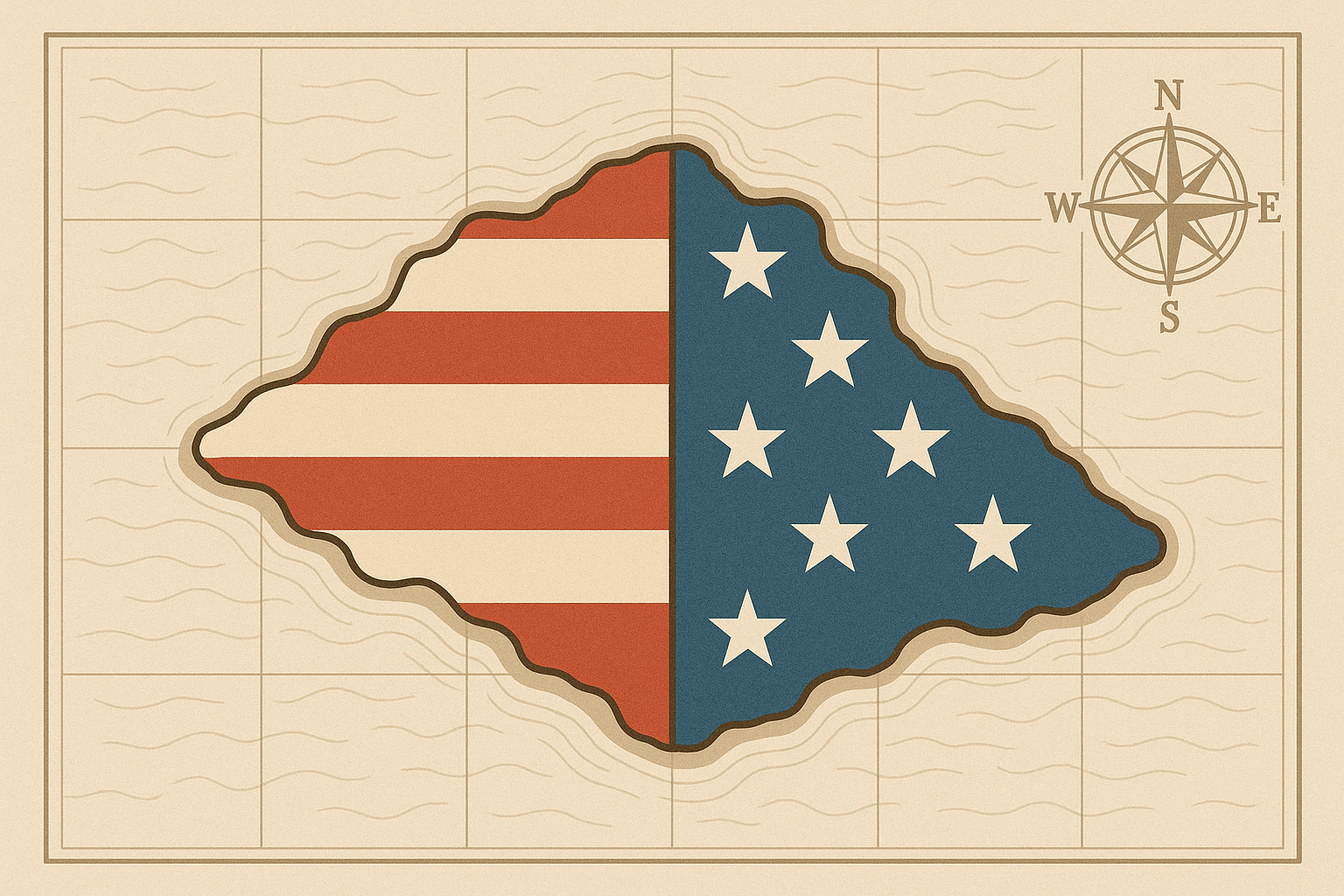

Imagine a border. You probably picture a line on a map, a fence, or a river dividing one nation from another. But what if the border wasn’t a line at all? What if, instead of dividing a piece of land, two countries decided to share it, ruling it together as equals? This isn’t a hypothetical puzzle; it’s a rare and fascinating geographical reality known as a condominium.

In the world of real estate, a condominium is a private residence within a larger building where common areas are jointly owned. In geopolitics, the principle is strikingly similar. A condominium is a territory where two or more sovereign powers formally agree to share equal rule—or dominium—over it. This is not a lease, a protectorate, or a vaguely defined sphere of influence. It is a formal, legal agreement of co-sovereignty, a paradox that challenges our neat, bordered understanding of the world.

The Island That Switches Countries

Perhaps the most famous and elegant example of a modern condominium is a tiny, uninhabited island nestled in the Bidasoa River, which marks the border between France and Spain. Known as Pheasant Island (Île des Faisans in French, Isla de los Faisanes in Spanish), this 1.6-acre patch of land has a truly unique administrative rhythm.

For six months of the year, from February 1st to July 31st, it is under French administration. Then, on August 1st, sovereignty is seamlessly transferred to Spain, where it remains until January 31st. This peaceful handover has occurred every year for over 360 years.

Why such a peculiar arrangement? The island’s status is a direct legacy of its role as a peacemaker. In 1659, after decades of war, France and Spain chose this neutral ground to negotiate and sign the Treaty of the Pyrenees. The treaty was sealed with a royal wedding between Louis XIV of France and Maria Theresa of Spain, which also took place on the island. To commemorate this hard-won peace, the two nations decided not to divide the island but to share it, making it a permanent symbol of their reconciliation.

The success of Pheasant Island lies in its simplicity.

- It’s uninhabited: There are no citizens to worry about, no conflicting legal codes to apply to daily life, and no taxes to collect.

– It’s symbolic: Its primary purpose is historical and ceremonial, not economic or strategic.

– It’s a shared responsibility: The physical geography of the island—a small, alluvial deposit—means it’s constantly at risk of erosion. France and Spain jointly fund the reinforcement of its banks, a physical manifestation of their shared commitment to preserving the peace it represents.

Access is forbidden to the public, adding to its mystique. The only people who set foot on it are officials from the naval commands of Bayonne (France) and San Sebastián (Spain) during the biannual handover ceremony or for maintenance work. It is a place literally set apart, governed by a timetable of shared peace.

Condominiums: From Rivers to Entire Nations

While Pheasant Island is the purest example, it’s not the only one. Condominiums have appeared in various forms, often as pragmatic solutions to managing shared resources or complex territorial disputes.

The Moselle River

A section of the Moselle River, along with its tributaries the Sauer and the Our, forms a condominium shared by Luxembourg and Germany. Established by a 1958 treaty, this arrangement covers the entire water body from bank to bank, including the locks and dams that make it navigable. Even the bridges that cross it are considered part of the condominium. This is a practical solution born of economic necessity, ensuring that a vital waterway is managed cooperatively for shipping and trade.

Lake Constance (Bodensee)

A much more ambiguous case is Lake Constance, bordered by Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. There is no formal treaty defining the international status of the main body of the lake (the Obersee). Austria maintains it’s a condominium, a view historically shared by the German state of Bavaria. Switzerland, however, argues that the border runs through the middle of the lake. Germany’s official position remains undefined. In practice, it functions as a condominium for matters like fishing and shipping regulations, but its legal status remains a fascinating, unresolved geographical puzzle.

A Historical “Pandemonium”

Condominiums become infinitely more complicated when people live in them. The most notorious example was the Anglo-French condominium of the New Hebrides, an archipelago in the South Pacific that existed from 1906 to 1980, when it gained independence as the nation of Vanuatu.

While the goal was to manage competing colonial interests, the reality was chaotic. It was nicknamed the “Pandemonium” because it had:

- Two separate legal systems (British and French)

- Two police forces

- Two health services

- Two school systems

- Two currencies circulating side-by-side

Residents had to navigate a bewildering dual administration. For instance, a person could be charged under French law and tried in a French court, or under British law in a British court. This experiment in joint rule over a populated territory proved so impractical and confusing that it serves as a historical lesson on why such arrangements are rarely attempted.

Why Are Condominiums So Rare?

The modern international system, largely defined since the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, is built on the concept of exclusive sovereignty. Nations are defined by clearly demarcated territory over which they, and they alone, have ultimate authority. Sharing this authority is a radical act that runs counter to the foundational principles of the nation-state.

The paradoxes are immense. Whose laws apply? Who collects taxes? What passport does a resident carry? How can two equal partners make decisions without perpetual gridlock? As the New Hebrides case shows, applying dual systems to a population is a recipe for confusion, not cooperation.

Condominiums, therefore, tend to only succeed under very specific conditions: when they are uninhabited, largely symbolic, cover a well-defined resource like a river, or serve as a temporary solution to a political impasse. They thrive on simplicity and a mutual desire for cooperation over conflict.

Geography Beyond Borders

Geopolitical condominiums are more than just historical footnotes or geographical oddities. They are living experiments in international relations. They force us to look beyond the hard lines on our maps and consider that borders can be zones of cooperation as well as division.

From the quiet, biannual exchange of sovereignty on Pheasant Island to the practical management of the Moselle River, these shared spaces offer a different model. They demonstrate that two nations can, in fact, share a single piece of the Earth, transforming a potential point of conflict into a symbol of enduring peace.