The Anatomy of a Newborn Landscape

When a glacier, a colossal river of ice, melts and pulls back, it doesn’t leave a clean slate. It leaves a chaotic, jumbled mess that is fascinating in its complexity. The landscape of a glacial forefield is a direct testament to the immense power of the ice that once covered it. Key features include:

- Moraines: These are ridges of unsorted rock and debris (called till) that were pushed and carried by the glacier. Terminal moraines mark the glacier’s furthest advance, while lateral moraines form along its sides. Walking across these unstable, bouldery ridges feels like navigating the earthworks of a giant construction site.

- Outwash Plains: As the glacier melts, torrents of water gush from its snout. These streams carry away finer sediments like sand and gravel, depositing them in a fan-shaped plain below the moraine. These are the floodplains of the new ecosystem.

- Glacial Lakes: Depressions scoured by the ice or valleys dammed by moraines often fill with meltwater, creating startlingly beautiful but sometimes dangerous proglacial lakes. Their iconic milky, turquoise color comes from suspended “glacial flour”—rock ground to a fine powder by the ice.

- Scoured Bedrock: Where the ice has scraped the land bare, you can often see polished rock surfaces etched with long grooves called glacial striations, marking the direction of the ice’s flow.

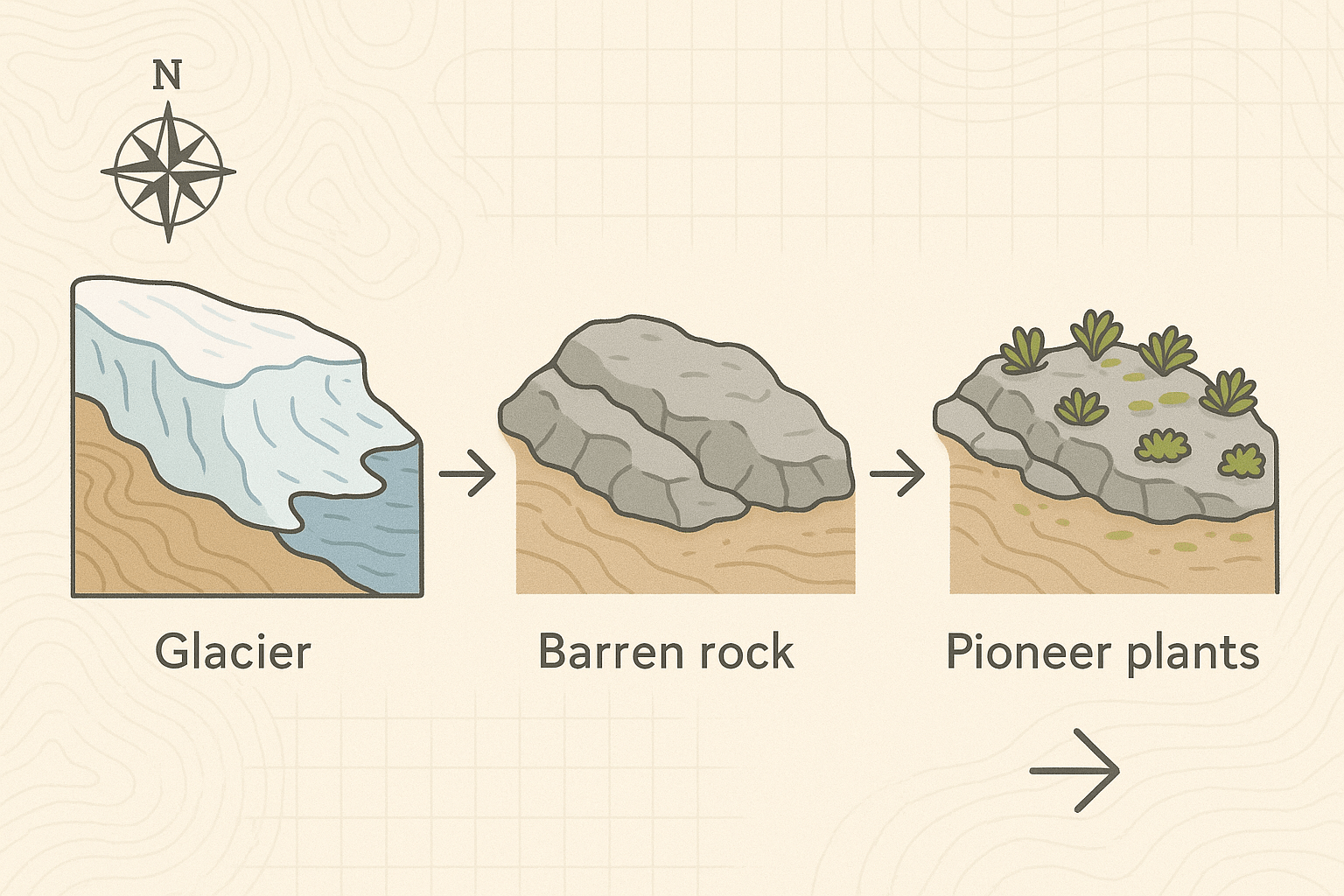

This barren, seemingly lifeless environment is the blank canvas upon which a new ecosystem will be painted. It’s a process geographers and ecologists call primary succession.

A Living Laboratory: Watching Life Take Hold

Primary succession is the colonization of a habitat that has never before supported life. Unlike succession after a forest fire, where soil and seeds remain, a glacial forefield starts with nothing but sterile rock and sediment. This makes them invaluable natural laboratories.

Scientists can use a concept called a chronosequence. By walking from the glacier’s current snout, across the recently exposed land, and towards the older, vegetated terrain further away, they are essentially walking through time. The landscape changes with every step, revealing the predictable stages of colonization:

- The Pioneers (Years 0-20): The very first arrivals are microscopic—bacteria and cyanobacteria that form dark crusts on rocks. They are soon joined by lichens and mosses, hardy organisms that can cling to bare rock, slowly breaking it down and trapping dust to create the first hint of soil.

- The Early Colonizers (Years 20-50): Once a thin layer of soil exists, hardy, wind-dispersed plants can gain a foothold. In many alpine regions, species like Purple Saxifrage and the fluffy-seeded Fireweed are among the first flowering plants.

- The Soil Builders (Years 50-150): Next come shrubs and small trees that can tolerate poor soil conditions. Alder is often a key species in this stage because it has a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing bacteria in its roots. It effectively fertilizes the soil, paving the way for other, more demanding species.

- The Climax Community (Years 150+): Eventually, a stable forest community, often of spruce, fir, or pine, can establish itself. This mature ecosystem is the final stage of succession.

One of the most famous places to witness this is Glacier Bay National Park in Alaska. When John Muir visited in 1879, the bay was choked with ice. Today, the glacier has retreated over 60 miles, and the land it left behind is covered in a lush spruce-hemlock rainforest, a perfect example of a century-long chronosequence.

A Global Tour of Emerging Landscapes

Glacial forefields are appearing in mountain ranges and polar regions all over the world, each with its own unique character.

- The European Alps: In countries like Switzerland and Austria, the retreat of glaciers like the Aletsch or the Pasterze is changing iconic mountain views. The newly exposed land is quickly becoming a focal point for scientific study and a new, more somber kind of tourism.

- The Andes: In Peru’s Cordillera Blanca, melting glaciers are a critical issue. While they reveal new land, they also feed dangerously unstable glacial lakes high above cities like Huaraz. The risk of a Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) is a constant threat to downstream communities.

- The Himalayas: Known as the “Third Pole”, this region is home to thousands of glaciers. In the Khumbu region of Nepal, near Mount Everest, the forefield of the Khumbu Glacier has become a permanent fixture on the trek to Base Camp, a stark reminder of the region’s rapid warming.

- Iceland: On this “Land of Fire and Ice”, glacial forefields have a unique volcanic twist. The dark basaltic sands and dramatic ice caves of the Sólheimajökull forefield create an otherworldly landscape that has become a popular destination for tourists and film crews alike.

The Human Dimension: A Double-Edged Sword

The emergence of glacial forefields is inextricably linked to human-caused climate change. They are both a consequence of our actions and a new frontier presenting unique risks and opportunities.

The primary risk is a Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF). When the natural moraine dam holding back a proglacial lake fails, it can release a catastrophic flood downstream, destroying villages, roads, and hydropower projects. Managing this risk is a major challenge for human geography in mountainous regions.

Furthermore, the very meltwater creating these landscapes is a vital resource. For millions of people from the plains of India to the farms of Peru, glaciers are a source of drinking water and irrigation, especially during the dry season. As they disappear, so does this critical water security.

Yet, these forefields also offer opportunities. They are unparalleled sites for research into climate change, ecology, and geology. They also create new, dramatic landscapes that drive tourism, although this must be managed carefully to protect the extremely fragile pioneering ecosystems.

Ultimately, a glacial forefield is a place of profound duality. It represents loss—the vanishing of ancient ice that has shaped our world for millennia. But it also represents birth—the creation of new land and the relentless, resilient march of life. They are the front line of climate change, a powerful, visible, and sobering reminder that the map of our world is not static, but is being redrawn before our very eyes.