Walk through the ruins of the Athenian Agora or stand before the stoic remains of Sparta, and a question inevitably arises: Why this? Why did Ancient Greece—the cradle of Western civilization—blossom into a fractured collection of hundreds of fiercely independent city-states, while its neighbors in Egypt and Persia built vast, unified empires? The answer is not found in a political treatise, but etched into the very landscape of the Hellenic peninsula. The rugged mountains and the surrounding seas were the true architects of Greek civilization, shaping everything from their politics and warfare to their democracy and mythology.

The Land of Stone and Struggle: The Reign of the Mountains

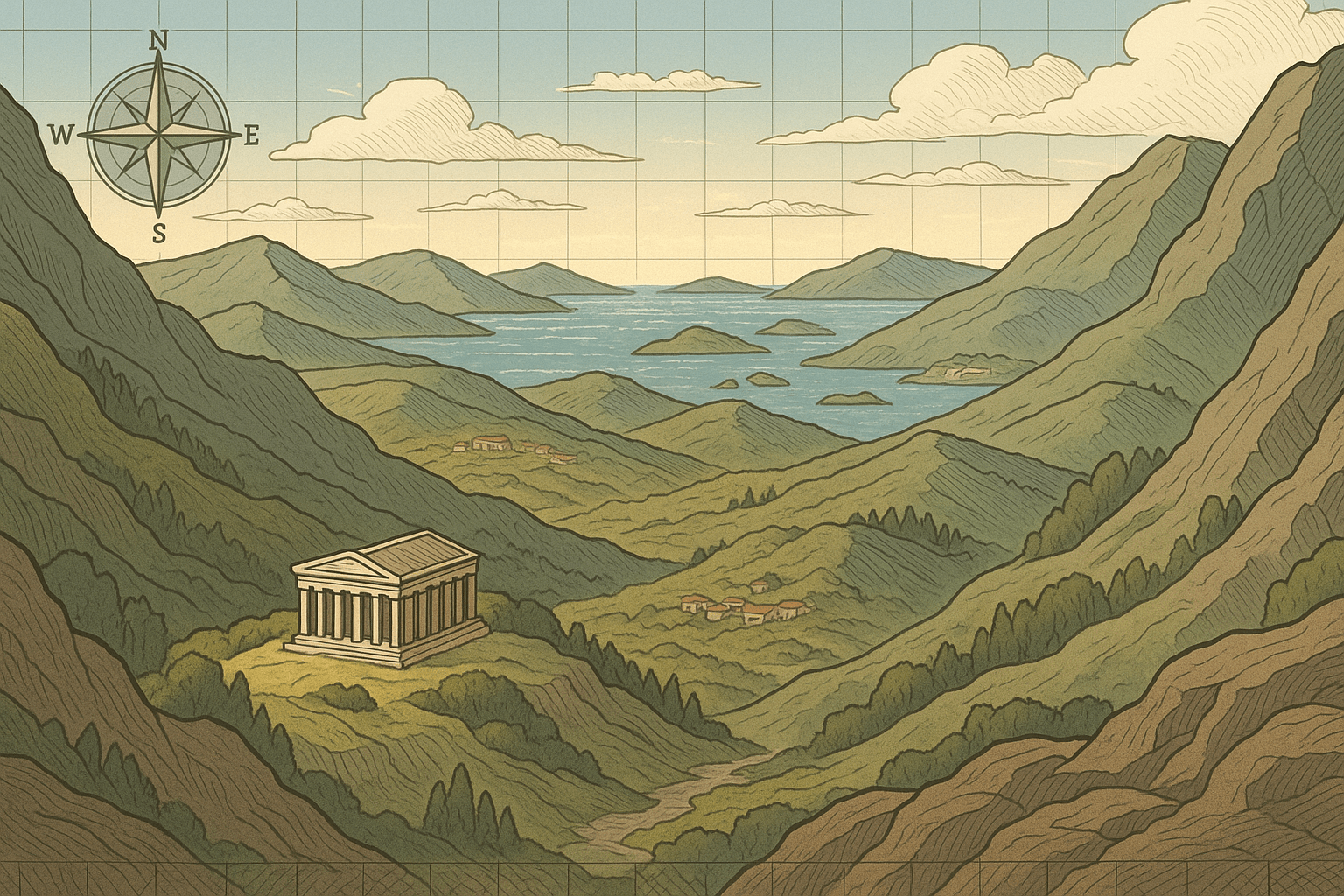

To understand ancient Greece, you must first understand its terrain. It is not a land of wide, fertile plains like the valleys of the Nile or the Tigris and Euphrates. Greece is, above all, a land of mountains. Roughly 80% of the country is mountainous, a formidable landscape of jagged peaks and steep-sided valleys. The mighty Pindus range, often called the “spine of Greece”, runs north to south, effectively dissecting the mainland.

This topography had profound consequences. These mountain ranges acted as colossal natural walls, isolating communities from one another. Travel by land was slow, arduous, and often dangerous. A journey that might take a few hours by car today could have taken days of navigating treacherous mountain passes. The result was the political fragmentation that defines ancient Greece. Communities developed in relative isolation within their own valleys, fostering an intense local identity.

This is the origin of the polis, or city-state. Athens was contained within the region of Attica, separated by mountains from Thebes in Boeotia, which was in turn walled off from Sparta in the Laconian plain. Each polis saw itself as a distinct nation, with its own government, laws, calendar, and patron deity. This fierce independence, born from geographic isolation, was a source of both incredible creativity and near-constant conflict.

Furthermore, the mountainous terrain severely limited agriculture. Only about 20% of the land was arable, or suitable for farming. This scarcity of fertile soil meant that Greece could not support a massive, centrally controlled agricultural system like Egypt’s. Farming was a small-scale, local affair. While the rocky hillsides were perfect for cultivating olives and grapes—the cornerstones of the Greek diet—growing staple grains like wheat and barley in large quantities was a constant challenge. This scarcity of land and resources was a primary driver of rivalry and warfare between neighboring city-states, as each sought to control what little fertile ground was available.

The Liquid Highway: The Call of the Aegean

If the mountains divided the Greeks, the sea united them—and connected them to the wider world. Greece has one of the longest coastlines of any country in the world relative to its size, with thousands of islands scattered across the Aegean and Ionian seas. For the ancient Greeks, the sea was not a barrier but a highway, a vast network of liquid roads.

It was often far easier and faster to sail from one coastal settlement to another than to attempt an overland trek. This maritime orientation turned the Greeks into some of the most skilled sailors and traders of the ancient world. They learned to navigate by the stars, harness the winds, and build resilient ships that could carry goods and people across the Mediterranean.

The sea provided what the land could not. It was a vital source of food through fishing and a gateway to trade. The Greeks imported essentials they lacked, like timber, metals, and, most importantly, grain, from regions around the Black Sea and Egypt. In return, they exported their own unique products: wine, olive oil, and beautifully crafted pottery. Cities with good harbors, like Athens with its port of Piraeus or Corinth on its strategic isthmus, became wealthy and powerful commercial hubs. The Athenian Empire of the 5th century BCE was built not on land, but on naval supremacy, enforced by its formidable fleet of trireme warships.

This maritime culture also fueled Greek colonization. As the population of a polis outgrew the capacity of its limited farmland, groups of citizens would set sail to found new, independent city-states across the sea. From Syracuse in Sicily to Massalia (modern-day Marseille) in France and Byzantium (modern-day Istanbul) in the east, Greek culture, language, and ideas spread throughout the Mediterranean basin.

Forging a Culture from the Landscape

This unique geography of isolated valleys and open seas didn’t just shape politics and economics; it forged the very soul of Greek culture.

Consider the birth of democracy. The small, intimate scale of the polis made direct democracy a practical possibility. In Athens, eligible citizens could gather in the agora (marketplace) or on the Pnyx hill to debate issues, propose laws, and vote directly on matters of state. Such a system would have been utterly impossible in a sprawling territorial empire where citizens were spread across thousands of square miles. Geography created the unique container in which the democratic experiment could flourish.

Even Greek mythology is profoundly tied to the physical world. The gods did not live in some abstract heaven but on Mount Olympus, the highest peak in Greece—a real, physical, and often cloud-shrouded place. Its imposing presence on the horizon was a constant reminder of the pantheon’s power. The treacherous seas, with their sudden storms and hidden rocks, were imagined to be the realms of Poseidon’s wrath and home to monsters like Scylla and Charybdis. The epic journey of Odysseus is, at its heart, a story of struggle against the sea. Sacred sites were chosen for their dramatic geography; the Oracle at Delphi, the most important shrine in the ancient world, was nestled in a breathtaking mountain sanctuary on the slopes of Mount Parnassus, its physical grandeur adding to its spiritual authority.

A Paradoxical Unity

Despite their fragmentation and incessant squabbling, the Greeks recognized a shared identity. How? Paradoxically, their geography played a role here, too. The same sea that connected them for trade also brought them into contact with non-Greek peoples, such as the Phoenicians, Egyptians, and especially the Persians. In defining themselves against these “barbarians” (a term that simply meant a non-Greek speaker), they reinforced their own shared Hellenic identity.

This was expressed through several Pan-Hellenic (all-Greek) institutions:

- The Olympic Games: Every four years, a sacred truce was declared, and athletes from across the Greek world, from Sparta to Sicily, gathered at Olympia to compete.

- Common Sanctuaries: Oracles and temples like the one at Delphi were revered and consulted by all city-states, acting as a kind of spiritual common ground.

- Shared Culture: All Greeks spoke dialects of the same language, worshipped the same gods, and were raised on the epic poems of Homer, which told of a time when their ancestors united to fight a common foe at Troy.

The mountains may have built the walls of the city-states, but the sea and the stories they told about their landscape provided the cultural glue that bound them together.

So, the next time you think of Ancient Greece, look beyond the marble temples and philosophical texts. Picture the shepherd on a steep hillside, the sailor navigating between islands, and the citizen casting a vote in a city nestled in a valley. The mountains and the sea were not merely a backdrop for their history; they were active, powerful forces that dictated the distinctive and enduring legacy of the Hellenic world.