The Unseen Architects of a Changing Planet

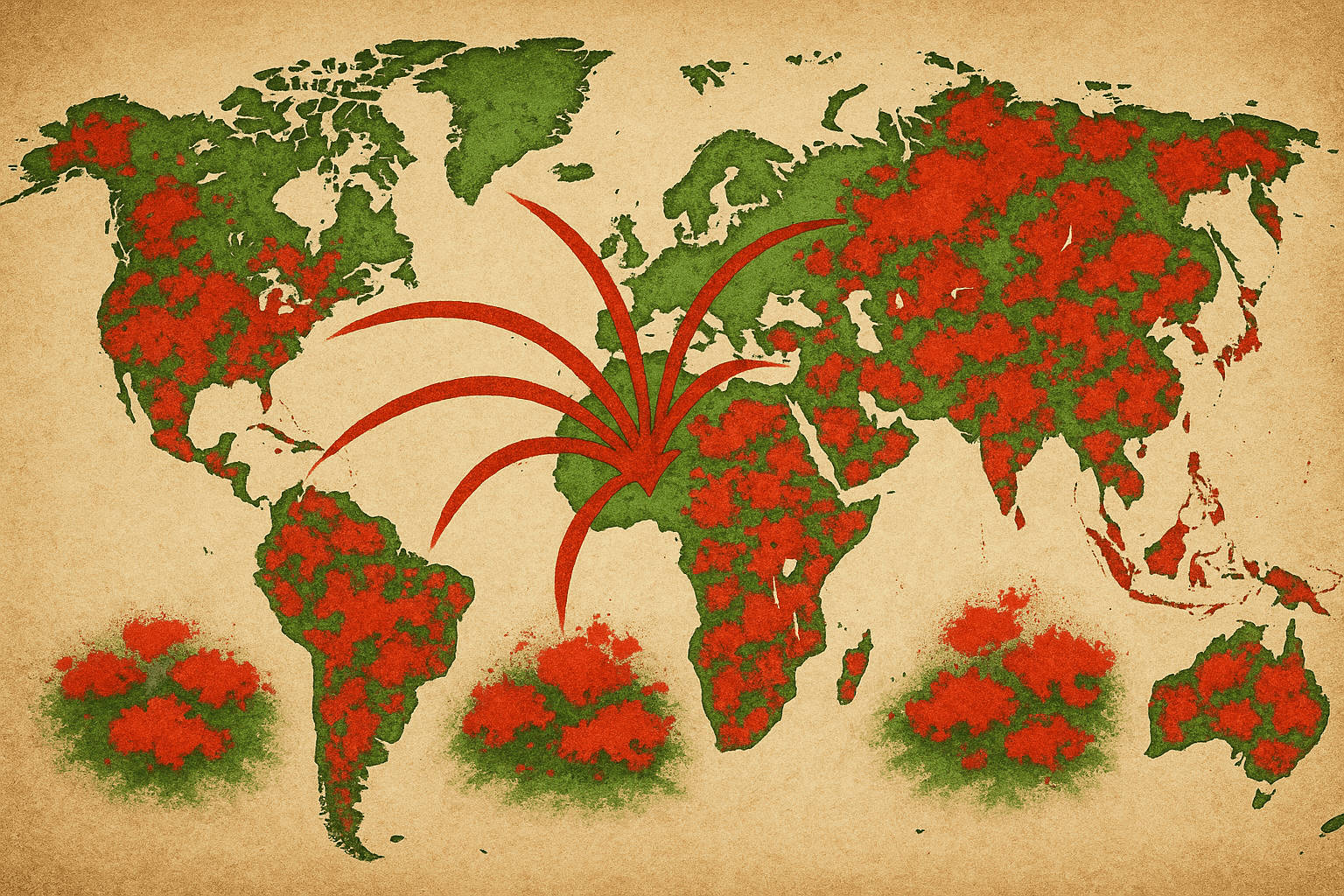

Our world, from a biogeographer’s perspective, is a magnificent mosaic. For millennia, oceans, mountain ranges, and deserts acted as formidable barriers, allowing life to evolve in splendid isolation. This gave rise to the unique biological signatures of different continents—the kangaroos of Australia, the lemurs of Madagascar, the towering redwoods of North America. But in the geological blink of an eye, humanity has torn down these barriers. Our globalized world of trade and travel has created superhighways not just for people and goods, but for species, launching an unprecedented biological reshuffling. These are the invasive species, the unwanted colonizers rewriting the ecological maps of our planet.

Pathways of the Invasion: How Hitchhikers Cross Continents

An invasive species doesn’t just appear; it’s transported. Understanding their spread is a lesson in human geography, tracing the lines of commerce and transit that connect our modern world. These species are often accidental tourists, stowaways on journeys they never intended to take.

Ballast Water: The Unseen Aquatic Stowaways

Imagine a massive cargo ship leaving a port in Europe, destined for the Great Lakes. To maintain stability on the open ocean, it pumps thousands of tons of local harbor water into its ballast tanks. When it arrives in North America and takes on cargo, it discharges that water—along with a teeming soup of microscopic life. This is precisely how one of the most infamous invaders arrived. The journey of the zebra mussel from the Ponto-Caspian region (the Black and Caspian Seas) to North America began in the ballast tank of a transatlantic freighter. This single, unintentional act in the late 1980s triggered an ecological and economic disaster that continues to unfold across the continent’s waterways.

Cargo and Commerce: The Trojan Horse

The container sitting on a ship or the wooden pallet in a plane’s cargo hold can be a Trojan Horse. Insects and pathogens can hide deep within wood, soil, or produce, emerging in a new land with no natural predators. The Emerald Ash Borer, an insect native to northeastern Asia, likely arrived in North America hidden in wooden packing materials. Since its discovery in Michigan in 2002, this tiny beetle has killed hundreds of millions of ash trees across more than 35 U.S. states and Canadian provinces, fundamentally altering the urban and natural forests of the continent.

The Best of Intentions: When Introductions Go Wrong

Not all introductions are accidental. Sometimes, we invite the invaders in. Species are often introduced for agriculture, aesthetics, or even misguided ecological control. Kudzu, a vine native to Japan and China, is a prime example. It was introduced to the United States at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition as a beautiful, fast-growing ornamental plant. Later, in the 1930s and 40s, the U.S. government actively promoted it for erosion control. The plan backfired spectacularly. In the warm, humid climate of the American Southeast, kudzu found a perfect new home, free from the insects and diseases that kept it in check in its native range.

Mapping the Spread: Two Case Studies in Ecological Conquest

Once an invasive species establishes a foothold, its spread can often be mapped along geographic features and human infrastructure, a relentless march across the landscape.

Case Study: The Zebra Mussel’s Blitz Through North America’s Waterways

After being discharged into Lake St. Clair, between Lake Huron and Lake Erie, around 1988, zebra mussels found an ideal environment. The Great Lakes offered abundant food and calcium-rich water perfect for shell-building. From this epicenter, their conquest began. They spread throughout the Great Lakes ecosystem with astonishing speed. But their true genius was exploiting the continent’s interconnected river systems. They were swept downstream into the Illinois River and from there, into the mighty Mississippi River. This single artery gave them access to a vascular network of tributaries spanning from Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico. Humans accelerated this spread even further; mussels attached to boat hulls, trailers, and fishing equipment were inadvertently transported overland, allowing them to “jump” entire watersheds into previously isolated lakes and reservoirs.

Case Study: Kudzu, the Green Blanket Smothering the American South

Kudzu’s geography is one of solar power and relentless growth. Thriving in the hot, humid conditions of the Southeastern United States, from East Texas to Florida and north to Pennsylvania, the vine’s range is primarily limited by physical geography—specifically, cold winter temperatures that kill it back to the roots. Within its ideal climate zone, it is an architectural and ecological force. Growing up to a foot a day, it drapes itself over entire forests, utility poles, abandoned cars, and buildings. It smothers native trees and shrubs by blocking out all sunlight, fundamentally changing the forest structure. The physical geography of the landscape is literally being reshaped, buried under a monolithic green blanket that alters soil chemistry and wipes out local biodiversity.

The Profound Impact: Reshaping Ecosystems and Economies

The arrival of an invasive species is not just the addition of a new player; it’s a fundamental disruption of the existing game. The consequences are both ecological and economic, creating ripple effects that can be felt for generations.

- Ecological Disruption: Invaders outcompete native species for food, light, and space. Zebra mussels filter so much plankton from the water that they decimate the food source for native fish and mollusks, causing entire food webs to collapse. This change in water clarity, while seemingly positive, allows sunlight to penetrate deeper, promoting the growth of aquatic weeds.

- Economic Havoc: The costs associated with invasive species are staggering. Municipalities and power plants along the Great Lakes and Mississippi River spend hundreds of millions of dollars annually to remove zebra mussels clogging their water intake pipes. The Emerald Ash Borer has cost communities billions in tree removal and treatment. In agriculture, invasive weeds and insects reduce crop yields and require expensive control measures.

A Shared Geographic Responsibility in a Borderless World

The story of invasive species is a stark reminder that in our interconnected world, ecological boundaries are more permeable than ever. The pathways of invasion are the pathways of human activity. Halting their spread requires a geographical approach—from strengthening biosecurity at our ports and airports to prevent new introductions, to coordinated management plans that recognize how species move across state and national borders.

On a personal level, our actions matter. Cleaning boats and fishing gear to prevent the spread of aquatic hitchhikers, choosing to plant native species in our gardens, and not releasing unwanted pets into the wild are all small but crucial acts of geographic stewardship. The unwanted colonizers are already here, but by understanding the maps of their movement, we have a better chance of protecting the native ecosystems that remain.