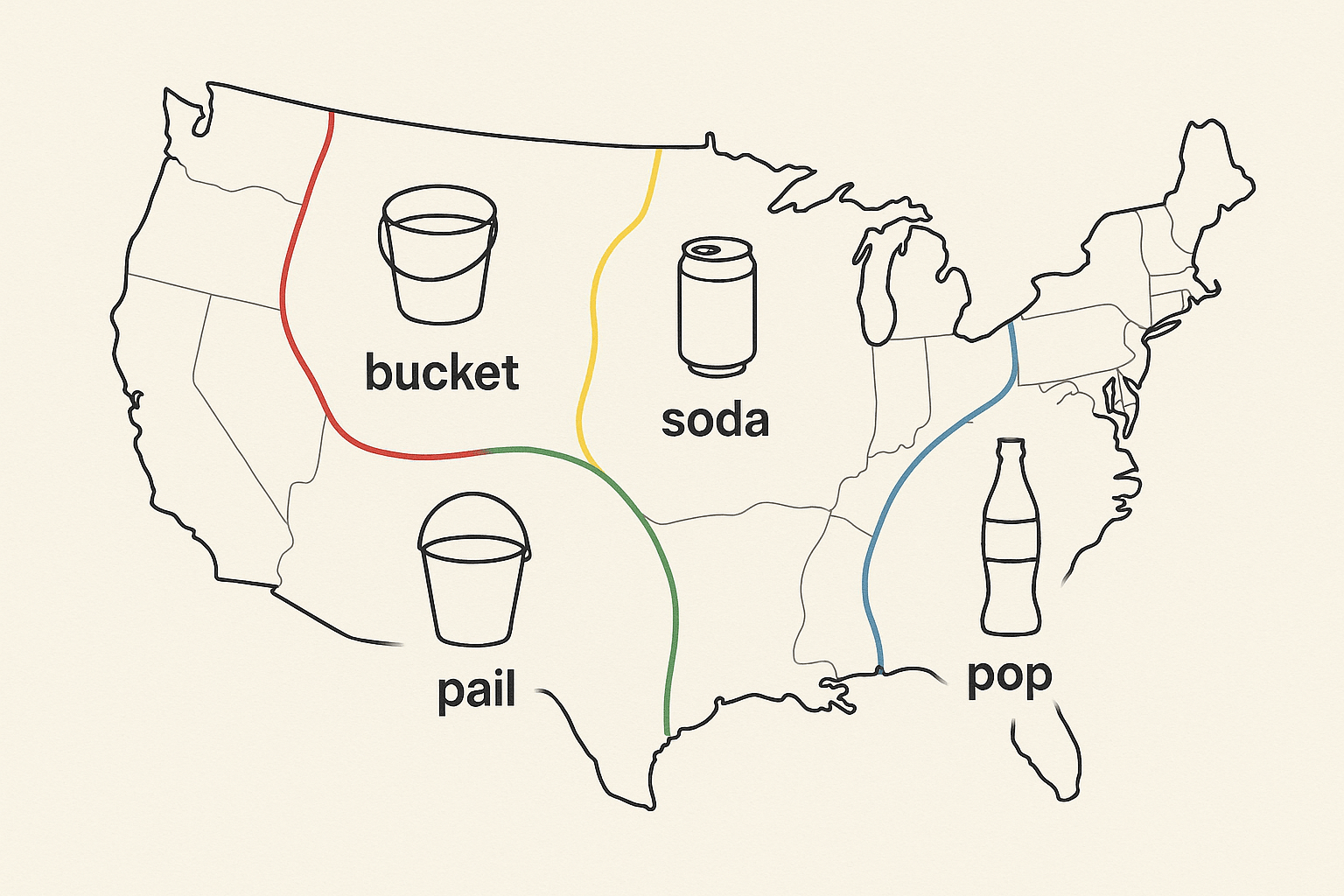

Do you drink soda, pop, or simply a coke (regardless of the brand)? Do you fetch water in a pail or a bucket? Do you call the long sandwich a sub, a hoagie, a grinder, or a hero? These aren’t just quirky regional preferences; they are data points on a hidden map. For geographers and linguists, these verbal divides are plotted as lines, creating a fascinating cartographic landscape of how we speak. These lines are called isoglosses, and they reveal much more than just our vocabulary—they trace the invisible footprints of history, migration, and culture across the globe.

What Is an Isogloss? A Contour Map for Language

At its core, an isogloss is a line drawn on a map to mark the boundary of a specific linguistic feature. The word itself comes from Greek: iso, meaning “equal”, and glossa, meaning “tongue” or “language.” Think of it like a contour line on a topographic map. While a contour line connects points of equal elevation, an isogloss connects points of equal language use—separating, for example, the region where people say “sneakers” from the one where they say “tennis shoes.”

An isogloss can track any number of features:

- Lexical: Differences in vocabulary (e.g., firefly vs. lightning bug).

- Phonological: Differences in pronunciation (e.g., the “r” sound in “car” being pronounced or dropped).

- Morphological: Differences in word structure (e.g., “dived” vs. “dove” as the past tense of “dive”).

- Syntactic: Differences in grammar (e.g., “The car needs washed” vs. “The car needs to be washed”).

A single isogloss is often a fuzzy, porous boundary. People on either side might understand each other perfectly well. But when several isoglosses—representing different linguistic features—bundle together and run along a similar path, they form a major dialect boundary. These isogloss bundles are where human geography gets truly interesting, as they often correspond with physical barriers, political borders, or ancient settlement patterns.

A Nation Divided by Words: Isoglosses of the United States

The United States is a perfect laboratory for observing how isoglosses tell a story of settlement and westward expansion. The major dialect regions of the American East Coast are direct echoes of the country’s colonial origins.

The Northern, Midland, and Southern Belts

Linguistic research has famously identified three primary dialect areas that originated with early English-speaking colonists:

- The North: Centered on Boston and settled primarily by Puritans from East Anglia in England. This region is known for dropping the “r” in words like “park” (pahk) and “car” (cah), and for vocabulary like pail and brook.

- The Midland: Centered on Philadelphia, this region was a melting pot of settlers, including Quakers from Northern England, Germans, and Scots-Irish. This diversity resulted in a more “neutral” accent that many consider to be “General American.” However, it has its own unique features, like the use of “anymore” in positive sentences (“Gas is expensive anymore”) and the persistence of German-influenced words like smearcase for cottage cheese.

- The South: Settled by colonists from Southern England in the Jamestown and Charleston areas, this region is known for features like the second-person plural “y’all”, the pin/pen merger (where both words sound the same), and a distinct vowel drawl.

The most fascinating part is how these linguistic patterns moved. As settlers pushed west in the 18th and 19th centuries, they carried their dialects with them. The isoglosses for Northern, Midland, and Southern features stretch across the country like contrails, following historic migration routes. The Midland dialect, for example, spread west along the Ohio River Valley, while Northern features fanned out through the Great Lakes region. The physical geography of the Appalachian Mountains initially acted as a formidable barrier, reinforcing these early coastal divides before pioneers found ways through the gaps, creating complex linguistic mixing zones on the other side.

Global Lines: Isoglosses as Historical Artifacts

This phenomenon isn’t unique to America. Across the world, isogloss bundles serve as living artifacts of deep history, conflict, and cultural exchange.

The La Spezia-Rimini Line

In Europe, one of the most significant isogloss bundles is the La Spezia-Rimini Line. Stretching across northern Italy, it separates the Northern Italian dialects (like Lombard and Venetian) from the Central and Southern dialects (like Tuscan and Neapolitan). To the north of this line, dialects share more in common with French and Catalan, while dialects to the south are closer to Standard Italian (which is based on Tuscan). This linguistic divide reflects ancient geography and history. It roughly follows the northern ridge of the Apennine Mountains and aligns with the boundary between the Romanized Celts of Cisalpine Gaul and the Italic peoples of the Roman Republic. Later, invasions by Germanic Lombards in the north further cemented this linguistic divergence.

The Centum-Satem Isogloss

Zooming out even further, one of the oldest and most profound isoglosses is the Centum-Satem divide. This line splits the entire Indo-European language family in two. It’s based on how the word for “one hundred” evolved from the ancestral Proto-Indo-European language.

- Centum Languages (Western group, including Germanic, Celtic, and Italic languages like Latin) pronounced the initial sound as a /k/. The word centum is Latin for 100.

- Satem Languages (Eastern group, including Slavic and Indo-Iranian languages like Sanskrit) pronounced it as a /s/. The word satem is from Avestan, an ancient Iranian language.

This massive isogloss represents a fundamental split among the peoples who migrated out of the Proto-Indo-European homeland thousands of years ago, a linguistic echo of one of humanity’s great prehistoric diasporas.

Blurring the Lines in a Modern World

So, are these lines permanent? Not at all. In our hyper-connected world, the forces shaping isoglosses are changing.

Urbanization is a major factor. Cities have always been linguistic melting pots, but modern metropolises act as “dialect levelers”, where people from different backgrounds converge and smooth over their sharpest regional features. At the same time, cities can become epicenters for new slang and pronunciations that then radiate outward.

Mass media and mobility have also had a profound impact. A standardized form of English, propagated through national news, movies, and the internet, erodes regional variations. As people move more freely for education and careers, the stable, geographically isolated communities that once incubated unique dialects are becoming rarer.

While some linguists mourn the potential loss of dialectal diversity, language is never static. As old isoglosses blur, new ones are constantly being drawn, perhaps no longer separating pail from bucket, but instead tracking the spread of new internet slang or the pronunciation shifts emerging in diverse urban centers.

The next time you travel and hear someone use a different word for a dragonfly, or pronounce a vowel in a way you’ve never heard, take a moment. You’re not just hearing a different word; you are standing on one side of an invisible line—an isogloss that tells a rich, geographic story of who we are and how we got here.