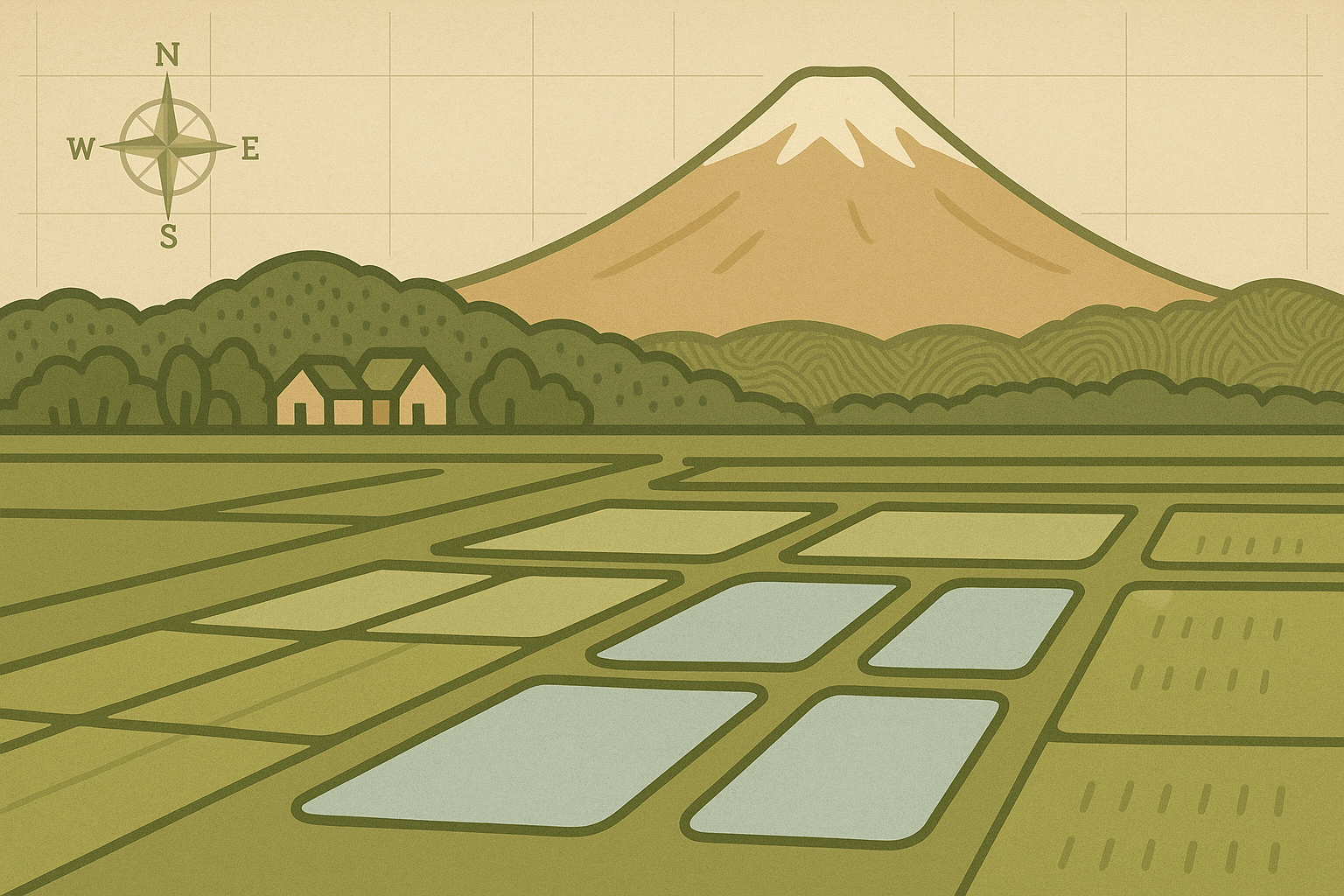

Venture beyond the neon glow of Tokyo and the serene temples of Kyoto, and you’ll find a different kind of Japanese landscape, one woven from centuries of human partnership with nature. This is the world of Satoyama (里山), a term that beautifully captures its essence: sato (里) meaning village or arable land, and yama (山) meaning mountain or forest. These are not pristine, untouched wildernesses, nor are they sprawling urban centers. Satoyama are the traditional mosaic landscapes of woodlands, grasslands, rice paddies, and streams that have been carefully managed by local communities for generations, creating a unique and stunningly biodiverse environment.

The Geography of a Living Mosaic

Geographically, Satoyama occupy a critical transition zone. They are nestled between the deep, remote mountains known as okuyama (奥山) and the flat, arable plains or heiya (平野) where larger settlements are typically found. This positioning is no accident; it is the key to their function. The landscape is a living, breathing system where each component serves a purpose and supports the others:

- Secondary Woodlands: These are not ancient, old-growth forests. They are coppice woodlands, where trees like oak and chestnut were cyclically cut to provide a sustainable supply of firewood and charcoal for fuel, timber for tools, and nutrient-rich leaf litter (ochiba) for fertilizer.

- Rice Paddies (Tanada): Often terraced on hillsides, these fields are the agricultural heart of the Satoyama. Their seasonal flooding creates temporary wetlands, crucial habitats for a vast array of life.

- Irrigation Ponds and Canals (Tameike): A sophisticated network of man-made ponds and waterways captures and distributes water from the mountain forests. They regulate water for the rice paddies while also serving as year-round aquatic habitats.

- Grasslands (Kayaba): These areas, often dominated by Japanese pampas grass (susuki), were managed to produce thatch for roofing traditional farmhouses (kominka) and fodder for livestock.

- Bamboo Groves: Cultivated for their versatile shoots for food and sturdy canes for construction and crafts.

This intricate patchwork creates countless “ecotones”, or edge habitats, where different ecosystems meet. It is in these transitions—from forest to field, from land to water—that biodiversity explodes.

Human Geography: A Culture of Coexistence

Satoyama are fundamentally socio-ecological landscapes. Their existence is inseparable from the human communities that shaped them. For centuries, rural life in Japan revolved around the cyclical harvesting of resources from the surrounding environment. This wasn’t exploitation; it was stewardship born of necessity. The health of the forest was directly linked to the yield of the rice paddy, and the purity of the stream was essential for the entire village.

This management was a community affair. Traditional practices were governed by collective rules that ensured resources weren’t over-extracted. Key activities included:

- Coppicing: A forestry technique where trees are cut to ground level, prompting new shoots to grow from the stump. This ensured a continuous supply of wood without killing the trees, maintaining the forest canopy in a constant state of renewal. This process also allowed more sunlight to reach the forest floor, encouraging a rich undergrowth of wildflowers.

- Kayakari: The annual cutting of pampas grass from the kayaba grasslands. This prevented the land from reverting to forest and maintained a unique habitat for grassland-specific plants and insects.

- Water Management: The meticulous maintenance of irrigation channels ensured equitable water distribution and prevented both flooding and drought, a testament to incredible hydrological engineering.

This deep, hands-on connection fostered a profound cultural respect for nature, woven into local festivals, folklore, and a sense of place.

A Surprising Hotspot for Biodiversity

While one might think pristine wilderness is the only place for high biodiversity, Satoyama landscapes prove otherwise. The constant, low-intensity human intervention created a stable mosaic of habitats that allowed a huge variety of species to thrive, many of which struggle in dense forests or monoculture farmlands.

The rice paddies, when flooded, become nurseries for frogs, dragonflies, and killifish. The irrigation ponds are home to amphibians like the Japanese giant salamander and provide foraging grounds for birds. The sun-dappled floors of coppiced woodlands are a haven for rare orchids and insects like the Giant Purple Emperor butterfly (Oomurasaki), Japan’s national butterfly, which feeds on the sap of sawtooth oak trees found in these managed forests. The return of majestic birds like the Oriental Stork to Japan has been heavily reliant on the restoration of these rich, paddy-centric feeding grounds.

The Threat of Decline and the Hope of Revival

Despite their immense value, Satoyama landscapes have been in decline since the mid-20th century. The reasons are rooted in Japan’s dramatic modernization:

- The Energy Revolution: The switch from charcoal and firewood to fossil fuels and electricity in the 1960s made coppicing economically obsolete.

- Agricultural Modernization: The introduction of chemical fertilizers and pesticides reduced the need for compost from the forest floor, and machinery made small, terraced paddies inefficient.

- Social Change: Mass migration from rural areas to major cities like Tokyo and Osaka, combined with an aging population, left villages without the younger generations needed to carry on the labor-intensive management practices.

As a result, many Satoyama were abandoned. Woodlands became overgrown and dark, grasslands were overtaken by forests, and biodiversity plummeted. However, a revival is underway. In recent decades, ecologists, conservation groups, and the government have recognized the immense ecological and cultural value of these landscapes. The “Satoyama Initiative”, a global partnership launched by Japan’s Ministry of the Environment and the United Nations University, aims to promote and support similar socio-ecological landscapes worldwide.

Today, NPOs and local volunteers work to restore traditional management practices. Ecotourism offers visitors a chance to participate in rice planting or charcoal making. Some corporations even fund Satoyama conservation as part of their corporate social responsibility, recognizing its importance for water security and cultural heritage. Places like the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture, designated as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS), stand as beacons of this revival, showcasing how Satoyama can be adapted for the 21st century.

A Blueprint for a Sustainable Future

Satoyama are more than just a picturesque feature of the Japanese countryside. They are a powerful lesson in geography—a living map of how human activity can be integrated with natural systems to create a landscape that is both productive and resilient. They remind us that sustainability is not about cordoning off nature from people, but about finding a wiser, more harmonious way to live within it.

As the world grapples with biodiversity loss and climate change, the enduring wisdom of Satoyama offers a hopeful blueprint—a model where human culture doesn’t just consume the environment, but actively cultivates and enriches it.