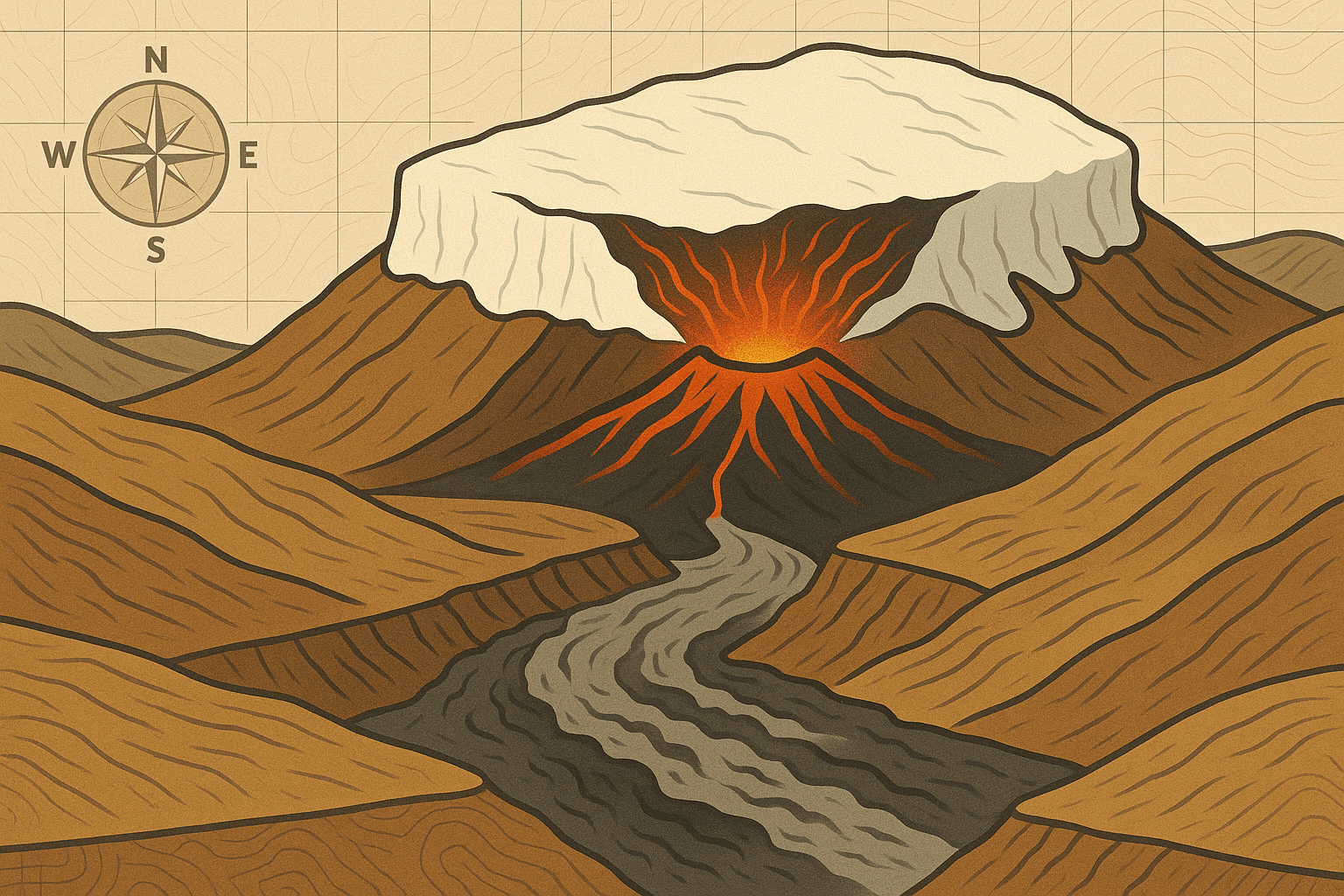

Imagine a volcano erupting. Now, picture that eruption happening directly beneath a glacier that is hundreds of meters thick. The immense heat instantly melts a colossal volume of ice, creating a vast, subglacial lake of trapped water. The pressure builds, the ice cap groans, and then, with unimaginable force, the dam breaks. This is a jökulhlaup—an Icelandic term meaning “glacial leap” or “glacial run”—and it is one of the most powerful and uniquely terrifying phenomena our planet can produce.

Nowhere on Earth is the stage more perfectly set for these catastrophic events than Iceland. This island nation is a geological marvel, a place where the raw forces of creation are on full display. To understand jökulhlaups, you must first understand the geography that makes them possible.

The Land of Fire and Ice: A Recipe for Catastrophe

Iceland’s dramatic nickname, “The Land of Fire and Ice,” isn’t just clever marketing; it’s a literal description of its physical geography. The “fire” comes from its position astride the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the tectonic boundary where the North American and Eurasian plates are pulling apart. This rift creates a volcanic hotspot, resulting in over 30 active volcanic systems dotting the island.

The “ice” comes from its high-latitude location in the North Atlantic. Despite the warming influence of the Gulf Stream, its climate is cold enough to support massive glaciers, or jöklar. In fact, over 10% of Iceland is covered by ice caps, including Vatnajökull, the largest ice cap in Europe by volume. It is this volatile combination—active volcanoes simmering directly beneath thick, heavy sheets of ancient ice—that provides the perfect ingredients for a jökulhlaup.

How to Brew a Glacial Flood

The formation of a jökulhlaup is a process of immense pressure and sudden release. It typically unfolds in a few key stages:

- Melting: A subglacial volcano begins to erupt, or geothermal heat from a magma chamber intensifies. This heat melts the base of the glacier, creating a growing cavity filled with meltwater.

- Containment: The sheer weight of the ice cap above acts as a formidable dam, trapping the water. The pressure inside this subglacial lake can become immense, sometimes causing the surface of the glacier to bulge upwards by several meters.

- The Breaking Point: Eventually, one of two things happens. The water pressure may become so great that it physically lifts the edge of the glacier, allowing the water to escape underneath. Alternatively, the water may melt a channel through the ice to the glacier’s edge.

- The Outburst: The release is not gradual; it is explosive. A torrent of water, mud, and ice bursts from the glacier’s snout. The discharge rate can be staggering, often exceeding the flow of the world’s mightiest rivers, like the Amazon or the Mississippi, for a short period.

Case Study: The Fury of Grímsvötn and Skeiðarársandur

Perhaps no place better illustrates the power of jökulhlaups than the area affected by the Grímsvötn volcano, which lies beneath the vast Vatnajökull ice cap. Grímsvötn is Iceland’s most frequently erupting volcano, and it regularly produces jökulhlaups that surge across the alluvial plain to its south, known as Skeiðarársandur.

In November 1996, a major eruption at Grímsvötn triggered one of the most well-documented jökulhlaups in modern history. After weeks of seismic activity, a flood with a peak flow estimated at 50,000 cubic meters per second—more than the average flow of the Amazon River—was unleashed. The torrent of black, sulfurous water carried with it icebergs the size of three-story buildings. It completely obliterated sections of Iceland’s iconic Ring Road (Route 1), twisting massive steel girders of the Skeiðará Bridge like pretzels and washing away kilometers of asphalt. The desolate, haunting remains of the bridge now serve as a permanent monument to the flood’s raw power.

This event demonstrated how jökulhlaups are not just floods; they are slurry flows of water, rock, and ice that have the power to fundamentally re-engineer the landscape in a matter of hours.

The Ever-Present Threat: Eyjafjallajökull and Katla

While the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull is globally famous for the ash cloud that paralyzed European air travel, it also produced significant jökulhlaups. These floods barrelled down the Gígjökull and Mýrdalsjökull outlet glaciers, threatening farms and infrastructure. In a remarkable display of human adaptation, Icelandic authorities, forewarned by monitoring systems, deliberately cut gaps in the Ring Road to allow the floodwaters to pass through, saving a crucial bridge from certain destruction.

However, the greatest fear for many Icelanders is Eyjafjallajökull’s much larger and more formidable neighbor: Katla. Hidden beneath the Mýrdalsjökull ice cap, Katla is one of Iceland’s most dangerous volcanoes. Historically, eruptions of Eyjafjallajökull have often been followed by an eruption from Katla within a few years. A major jökulhlaup from Katla would be an order of magnitude larger than the 1996 Grímsvötn event, posing an existential threat to the coastal town of Vík and its surroundings. The potential flood path is well-mapped, and evacuation drills are a regular part of life for residents.

Sculpting Landscapes, Shaping Lives

Beyond their destructive capacity, jökulhlaups are a primary force of geographical creation in Iceland. The vast, flat, black-sand plains (sandurs) that characterize much of Iceland’s south coast, like Skeiðarársandur, were built entirely by sediment deposited by countless jökulhlaups over millennia.

These floods also carve some of the country’s most spectacular canyons. The immense Jökulsárgljúfur canyon in North Iceland, which contains the powerful Dettifoss waterfall, is believed to have been formed by a series of colossal prehistoric jökulhlaups.

From a human geography perspective, living with jökulhlaups has deeply influenced Icelandic engineering, settlement patterns, and national psyche. The Icelandic Meteorological Office maintains a sophisticated 24/7 monitoring network of GPS stations, seismometers, and river gauges to provide early warnings. Infrastructure is designed to be either incredibly robust or, in some cases, sacrificially weak to protect more valuable assets. It’s a constant, dynamic dialogue between a technologically advanced society and one of the most powerful elemental forces on the planet.

Jökulhlaups are a humbling reminder that on this island of fire and ice, the land is never truly static. It is a world in motion, a landscape being violently and beautifully reshaped by the primal forces still brewing just beneath the surface.