Look at a map, and you see a world of familiar patterns: rivers snaking their way to the sea, mountain ranges rising in jagged lines, and plains stretching out in vast, uniform expanses. But in certain corners of the globe, the rules of surface geography seem to break down. Here, rivers vanish without a trace, the ground can swallow entire buildings, and forests made not of trees but of stone reach for the sky. This is the world of karst topography, a surreal and captivating landscape carved by water, one drip at a time.

The Chemistry of a Disappearing World

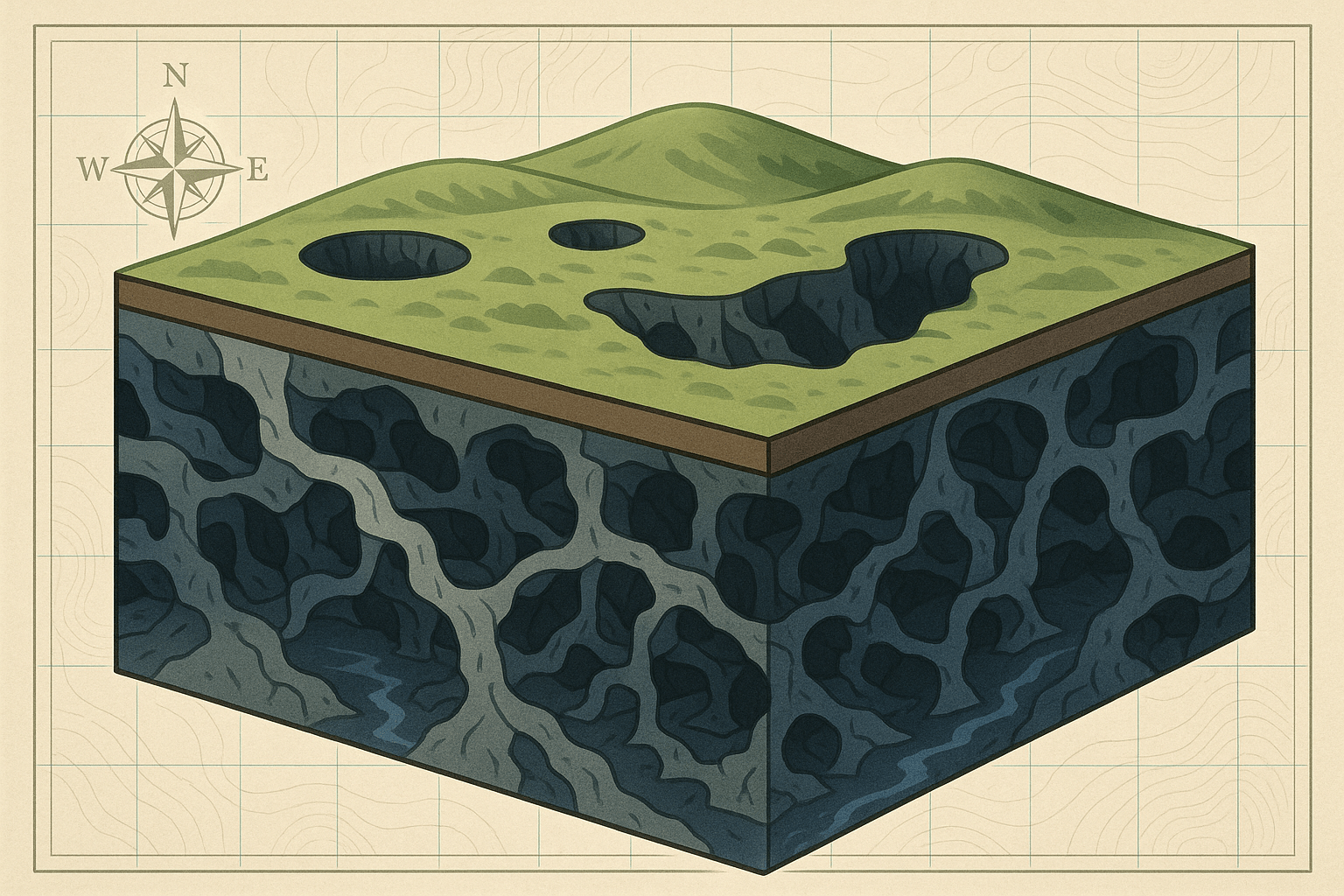

At its heart, karst is a story of dissolution. It’s a landscape formed when soluble bedrock, most commonly limestone or dolomite, is slowly dissolved by slightly acidic water. It sounds simple, but the process creates some of the most complex and bewildering terrain on Earth.

The magic ingredient is carbonic acid. As rain falls through the atmosphere, it picks up carbon dioxide (CO₂), forming a weak acid (H₂CO₃). When this mildly acidic water seeps into cracks and fissures in limestone (calcium carbonate), it triggers a chemical reaction. The acid dissolves the rock, carrying it away in solution as calcium bicarbonate. Over millennia, this persistent, patient process sculpts the land from both above and below, creating a dual world of surface wonders and subterranean labyrinths.

The Signature Features of a Karst Landscape

Karst regions are characterized by a distinct set of features that often defy the logic of typical landscapes. The drainage is not on the surface, but through the ground itself.

On the Surface (Epikarst)

- Sinkholes (Dolines): Perhaps the most famous and feared karst feature, sinkholes are depressions in the ground where the underlying rock has dissolved or a cave roof has collapsed. They can range from small, gentle bowls to vast, sheer-walled chasms hundreds of meters deep.

- Disappearing Streams: In a karst area, it’s common to see a river flowing along happily, only to abruptly plunge into a hole in the ground (a ponor) and vanish. This water doesn’t disappear; it simply continues its journey underground.

- Karren or Lapiez: On exposed limestone surfaces, rainwater etches intricate patterns of small channels, grooves, and sharp ridges. Walking across a field of karren can feel like traversing a field of razors.

- Poljes: These are large, flat-floored depressions with steep sides, often covering many square kilometers. Unlike rugged sinkholes, their floors are often covered with sediment, making them fertile oases for agriculture in an otherwise rocky and unforgiving landscape.

Beneath the Surface (Endokarst)

- Caves and Caverns: The ultimate expression of karst is the cave. As water works its way deeper, it enlarges cracks and conduits into vast networks of passages and chambers, creating a hidden world of darkness and wonder.

- Speleothems: These are the breathtaking decorations inside caves. As water rich in dissolved calcite drips from the ceiling or flows down walls, it re-deposits the mineral, slowly building formations. The most well-known are stalactites (hanging from the ceiling) and stalagmites (growing from the floor).

- Underground Rivers: The streams that vanish from the surface become powerful underground rivers, carving out cave passages and supplying massive, hidden aquifers.

A Global Tour of Karst Wonders

While karst features exist worldwide (about 15% of Earth’s land is karst), some regions showcase them on a truly epic scale.

The Dinaric Alps, Europe: The very word “karst” comes from the Kras Plateau, a region spanning Slovenia and Italy. This area is considered the “classical karst.” The Dinaric Alps, stretching through Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro, are a textbook example of this topography. The landscape is rugged and water is scarce on the surface, forcing life to adapt. It’s home to some of the world’s most significant cave systems, like Slovenia’s Postojna Cave and the UNESCO-listed Škocjan Caves, where the Reka River thunders through one of the largest underground canyons on the planet.

South China Karst: A UNESCO World Heritage Site, this region showcases a different, more dramatic expression of karst, shaped by a humid tropical climate. In places like Guilin, the landscape is dominated by spectacular tower karst (fenglin), where immense limestone peaks rise vertically from a flat plain, creating the dreamlike scenery immortalized in Chinese art. Further south, the Shilin (Stone Forest) near Kunming presents a jaw-dropping maze of sharp, grey limestone pinnacles that look like a petrified forest.

Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico: The flat limestone shelf of the Yucatán is famous for its cenotes. These are sinkholes that have collapsed to expose the groundwater beneath, creating stunning natural swimming holes. For the ancient Maya civilization, cenotes were not just the primary source of fresh water; they were sacred portals to the underworld, or Xibalba.

Life in a Karst World: Fragile Hydrology and Ecosystems

Living in a karst region presents unique challenges. The primary one is water. Because water flows rapidly through large underground channels instead of filtering slowly through sand and soil, karst aquifers are extremely vulnerable to pollution. A spill on the surface can contaminate a community’s water supply miles away in a matter of hours.

The ecosystems are just as unique. Caves are home to highly specialized creatures known as troglobites. Having adapted to a world of absolute darkness and limited food, these animals, like the blind olm (a cave salamander from the Dinaric Alps), often have no eyes, no pigmentation, and heightened non-visual senses. On the surface, the thin soils and peculiar drainage patterns support rare plant species found nowhere else.

The Human Connection

From an engineering perspective, karst is a nightmare. The ground is unstable, making it difficult to build roads, dams, and buildings. Finding a reliable water source can be a constant struggle. For agriculture, the rocky terrain and thin soils are challenging, making the fertile poljes incredibly valuable.

Yet, these same challenges create opportunity. Karst landscapes are a massive draw for tourism, from recreational caving (spelunking) to sightseeing in places like New Zealand’s Waitomo Glowworm Caves or Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave National Park, the longest cave system in the world. They are a source of cultural identity and mythology, and a living laboratory for scientists studying geology, hydrology, and biology.

The world of karst is a powerful reminder that some of Earth’s most spectacular features are hidden just out of sight. It is a landscape of profound beauty and fragility, a world beneath our feet that commands both our curiosity and our respect.