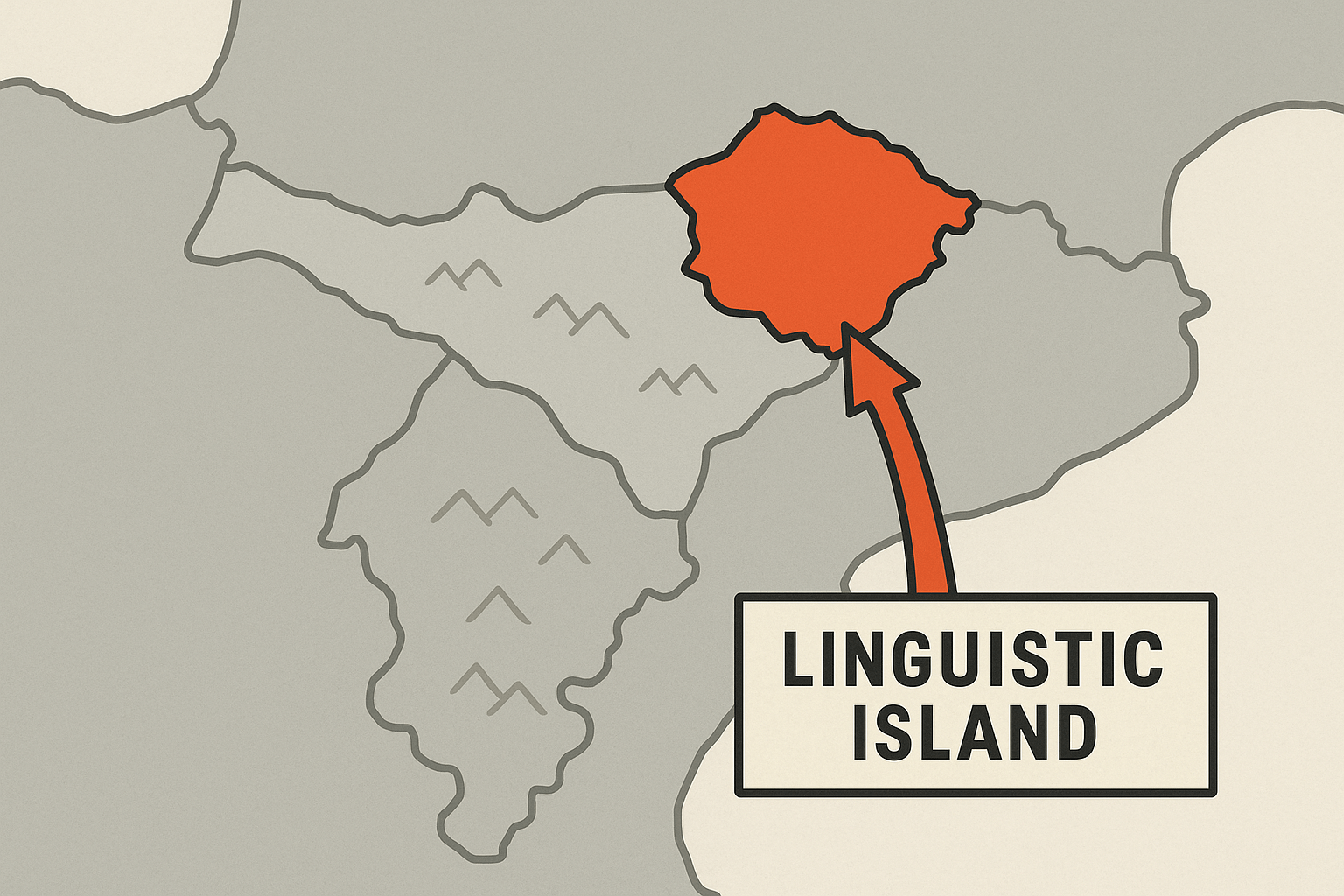

Imagine trekking across the vast plains of Spain, where the melodious sounds of Spanish, a Romance language with Latin roots, fill the air. Then, as you enter the jagged, misty peaks of the Pyrenees, you stumble upon a village where the signs are unreadable and the local tongue sounds like nothing you’ve ever heard. This language, ancient and complex, belongs to no known family on Earth. You’ve just discovered a linguistic island—a community whose language is a living fossil, completely unrelated to the sea of languages surrounding it.

These linguistic islands are not just curiosities; they are profound stories of human history, migration, and survival, written directly onto the physical map of our world. They are testaments to how geography—in the form of mountains, swamps, and remote valleys—can act as a fortress, preserving the echoes of a lost time.

The Geography of Isolation

What creates a linguistic island? The answer almost always lies in a combination of physical and human geography. A language that was once widespread becomes an “island” when new languages sweep across the land, failing to penetrate certain pockets of resistance. These pockets are often defined by formidable natural barriers.

- Mountain Ranges: The most classic incubator for linguistic islands. Rugged, high-altitude terrain creates natural fortresses. Valleys separated by towering peaks can lead to centuries of isolation, protecting communities from invaders, traders, and the cultural influence of the lowlands.

- Swamps and Dense Forests: Just as mountains create vertical barriers, impenetrable wetlands and jungles create horizontal ones. These environments are difficult to traverse and conquer, allowing indigenous populations to maintain their linguistic and cultural autonomy.

- Migration Waves: The “sea” around the island is just as important. A linguistic island is often a remnant—the last unsubmerged peak of a linguistic continent that was flooded by a new language family. The Indo-European expansion across Europe, for example, left behind older languages in the continent’s most inaccessible corners. The same can be said for the Bantu expansion across sub-Saharan Africa.

These geographic factors create a petri dish for linguistic preservation. While the surrounding lands undergo waves of change, the language on the island remains, a snapshot of a much older linguistic landscape.

Case Study: The Basque Country, Europe’s Oldest Voice

There is no better example of a linguistic island than the Basque people. Nestled in the western Pyrenees, straddling the border between Spain and France, the Basque Country is home to Euskara, a language so unique it is classified as a language isolate. It has no demonstrable genetic relationship to any other language in the world.

How did it survive? The answer is etched into the very mountains it calls home.

Euskara is a pre-Indo-European language. This means it was spoken in Western Europe before the arrival of the Celtic, Latin, and Germanic tribes whose languages would come to dominate the continent. As Indo-European speakers spread across the fertile plains of modern-day France and Spain, the rugged topography of the Pyrenees provided a sanctuary for the Proto-Basque speakers. The Romans, who so effectively spread Latin throughout their empire, found it difficult and unprofitable to fully subdue the fierce tribes of these mountains. Later, Visigoths and Moors also failed to assimilate them completely.

The geography of the Basque Country—a land of steep valleys, misty forests, and a strong maritime tradition on the Bay of Biscay—fostered a fiercely independent culture. This powerful sense of identity, born from geographic seclusion, became the ultimate guardian of the Euskara language against the immense pressures of Spanish and French for over two millennia.

An Archipelago of Tongues: The Caucasus and Beyond

While the Basque Country is a singular island, some geographical regions act as entire archipelagos, hosting a dizzying diversity of languages in a small area. The most famous of these is the Caucasus Mountains.

The Caucasus: A Mountain of Languages

Stretching between the Black and Caspian Seas, the Caucasus region is arguably the most linguistically complex place on Earth for its size. The extreme geography, with deep, isolated valleys separated by some of Europe’s highest peaks, has created a patchwork of distinct ethnic and linguistic groups. This is not one island, but dozens. The region is home to three indigenous language families—Kartvelian (like Georgian), Northeast Caucasian, and Northwest Caucasian—found nowhere else on the planet.

Here, geography is destiny. A journey of just 50 kilometers can take you from a community speaking a Turkic language to another speaking an Indo-European one, and then to a third speaking a language whose origins are a complete mystery. The mountains served as a refuge for countless groups fleeing conflict and assimilation on the open steppes to the north and the plains to the south.

The Hunza Valley: Language in the “Roof of the World”

Far to the east, in the Karakoram Mountains of northern Pakistan, lies another remarkable linguistic island. In the stunningly beautiful Hunza Valley, surrounded by peaks soaring over 7,000 meters, the Burusho people speak Burushaski. Like Basque, it is a language isolate with no known relatives.

The Burusho are encircled by speakers of Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages, yet their tongue remains an enigma. Their survival is a direct result of living in one of the most remote and inaccessible places on the planet. Until the construction of the Karakoram Highway, the Hunza Valley was almost entirely cut off from the outside world, allowing the Burushaski language to thrive in splendid isolation.

The Fragile Future of a Mapped Heritage

For millennia, physical geography was the staunchest defender of these linguistic relics. A mountain pass was a real barrier. A dense jungle was a deterrent. Today, however, those geographic barriers are being erased by a new kind of geography—one of fiber-optic cables, highways, and global media.

Globalization, urbanization, and the internet are connecting the world’s most remote corners. While this brings economic and social opportunities, it also poses an existential threat to linguistic islands. Young people move to cities for work, adopting the dominant national language. Television and social media beam in content in English, Spanish, or Mandarin, making local tongues seem less relevant.

The story of linguistic islands is therefore a race against time. Revitalization efforts, like those that have successfully brought Basque into schools and government, offer hope. These languages are more than just words; they are unique worldviews, libraries of traditional ecological knowledge, and direct links to a human past that predates our recorded histories. They are a map of our deep heritage, and if they vanish, that map will have lost some of its most fascinating and irreplaceable landmarks.