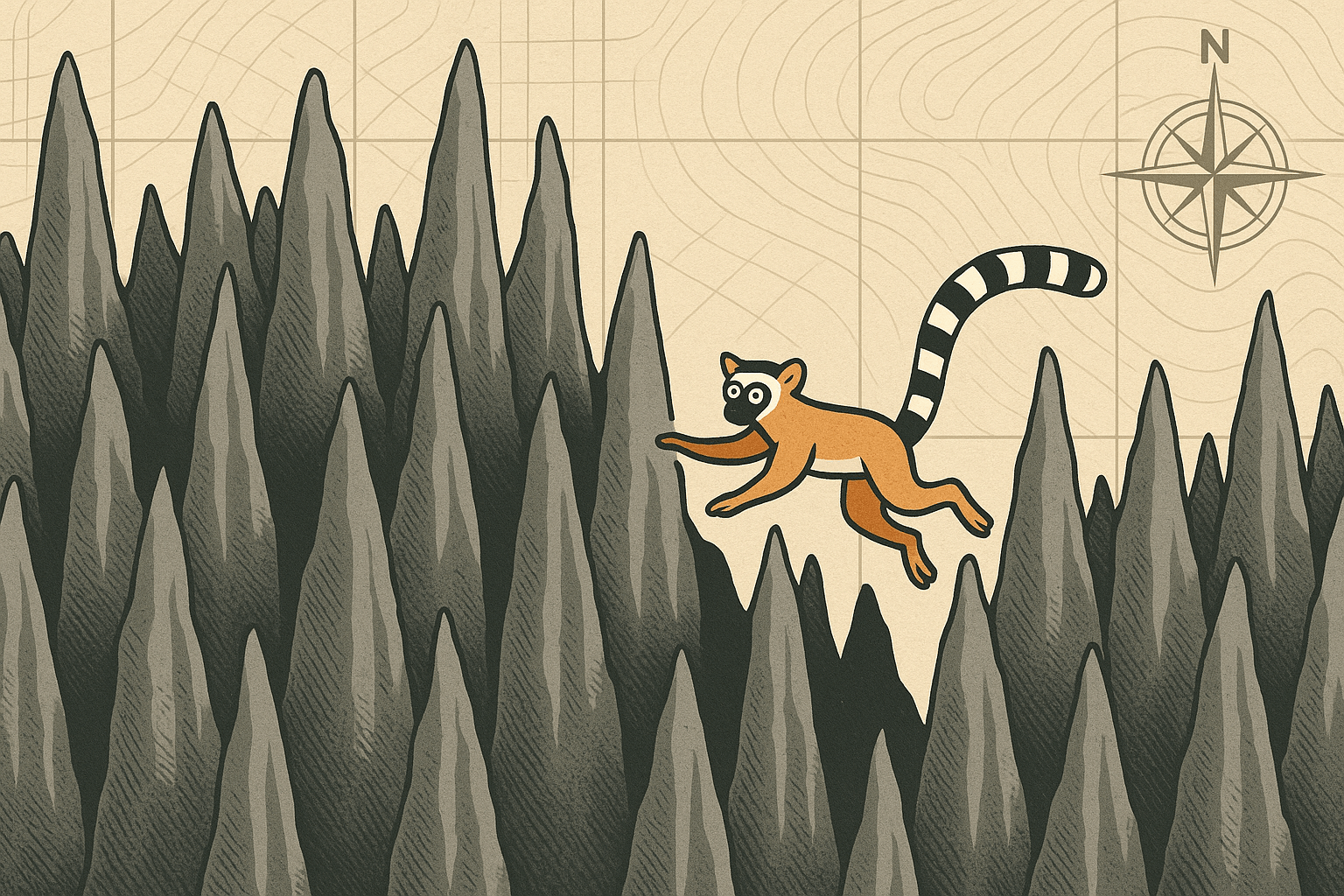

Imagine a forest forged not from wood, but from stone. Picture a landscape of vertical, razor-sharp limestone pinnacles reaching for the sky, creating a labyrinth so dense and treacherous that its name literally means “where one cannot walk barefoot.” This is not a scene from a fantasy novel; this is Madagascar’s Tsingy, one of the most spectacular and surreal geographical phenomena on our planet.

This otherworldly stone forest is a testament to the slow, powerful artistry of nature and a sanctuary for life that has adapted in the most extraordinary ways. Let’s journey into the heart of this geological marvel to understand how it came to be and what secrets it holds within its jagged spires and shadowed canyons.

A Landscape Carved by Water and Time

The story of the Tsingy begins around 200 million years ago, during the Jurassic period. The region was a vast, shallow sea, where layers upon layers of coral and seashells accumulated on the ocean floor. Over millennia, these deposits were compacted into a massive limestone plateau.

The real magic started when tectonic forces lifted this plateau above sea level. This exposed the soft limestone to Madagascar’s two most powerful sculptors: water and time. This type of landscape, formed by the dissolution of soluble rock like limestone, is known as a karst landscape.

The process unfolded in two primary ways:

- Vertical Erosion: Heavy monsoon rains, naturally slightly acidic, fell upon the limestone. The water seeped into cracks and fissures, slowly dissolving the rock and carving deep, vertical gorges. These narrow slots are known as “grikes.”

- Horizontal Erosion: Simultaneously, groundwater, which is even more acidic, chewed away at the base of the plateau. It carved out a vast network of underground rivers, caves, and caverns, undermining the structure from below.

The result of this top-down and bottom-up erosion is the dramatic landscape we see today. The remaining blocks of limestone, called “clints”, have been honed by the elements into the iconic, needle-like spires of the Tsingy. The surface is a chaotic maze of sharp edges, while beneath lies a hidden world of subterranean passages.

The Stone Sanctuaries: Where to Find the Tsingy

These magnificent formations are primarily found along the western coast of Madagascar. The two most significant and protected areas offer a glimpse into this unique world, each with its own distinct character.

Tsingy de Bemaraha National Park

This is the star of the show. A UNESCO World Heritage site since 1990, Tsingy de Bemaraha is a vast, 1,575-square-kilometer reserve that contains the most famous and dramatic formations. It’s divided into two parts: the “Great Tsingy”, with its towering, formidable spires, and the “Little Tsingy”, featuring smaller, more accessible pinnacles.

Reaching Bemaraha is an adventure in itself, often involving a rugged 4×4 journey from the coastal city of Morondava—a city famous for another Malagasy icon, the Avenue of the Baobabs. The park represents a crucial stronghold for the unique biodiversity of western Madagascar.

Ankarana Special Reserve

Located further north, Ankarana offers a different, but equally fascinating, Tsingy experience. While it also features the characteristic sharp pinnacles, Ankarana is renowned for its immense underground network. It boasts one of the largest and longest cave systems in Africa, with subterranean rivers that local communities hold sacred. The forest canopy here often grows right over the Tsingy, creating a unique fusion of green forest and grey stone.

Life on a Razor’s Edge: A Hotspot of Adaptation

The true wonder of the Tsingy is not just its geology, but the incredible biodiversity it supports. The extreme topography has created a mosaic of micro-habitats, forcing life to adapt in ingenious ways. The ecosystem is distinctly “vertical”:

- The Exposed Summits: The sun-baked tops of the pinnacles are hot and dry. Here, you’ll find xerophytes—plants adapted to arid conditions, such as succulents like pachypodiums and aloes.

- The Slopes and Gorges: The narrow canyons between the spires are shaded, cool, and humid. This environment supports a completely different community of plants, including ferns, mosses, and figs.

– The Caves and Caverns: The dark, subterranean world is home to its own cast of characters, including vast colonies of bats, blind cave fish, shrimp, and specialized insects.

This isolation and variety of habitats have made the Tsingy a cradle of endemism, meaning a high percentage of its species are found nowhere else on Earth. The most charismatic residents are undoubtedly the lemurs. The Decken’s Sifaka and the Red-fronted Brown Lemur have adapted to this treacherous terrain with astonishing agility. They navigate the stone forest by executing powerful, precise leaps from one razor-sharp pinnacle to the next, a feat that is breathtaking to witness.

But the diversity doesn’t stop there. The Tsingy is a haven for over 100 species of birds, including the critically endangered Madagascar Fish Eagle. It’s also home to a plethora of reptiles and amphibians, such as the bizarre leaf-tailed geckos and the highly threatened Antsingy leaf chameleon (*Brookesia perarmata*), a master of camouflage perfectly suited to the forest floor litter.

Navigating the Impassable: Human Geography and Ecotourism

For centuries, the impenetrable nature of the Tsingy made it a natural fortress. Local people, including the island’s earliest inhabitants, the Vazimba, and later the Sakalava people, used the stone labyrinth as a refuge during times of conflict. The sharp spires and hidden caves provided a near-perfect defense system.

Today, human interaction with the Tsingy has transformed. What was once impassable is now accessible to adventurous travelers, thanks to remarkable feats of engineering. To protect both visitors and the fragile environment, a system of steel cables, rope bridges, sturdy ladders, and harnesses has been installed. This “via ferrata” (iron road) allows you to securely traverse deep canyons and climb the pinnacles, offering spectacular views and an intimate look at the landscape.

This ecotourism is vital. It provides a sustainable income for local communities, turning former poachers into passionate guides and giving the Malagasy people a direct economic incentive to protect their unique natural heritage. A visit to the Tsingy is not just a geographical expedition; it’s a lesson in community-based conservation.

The Tsingy of Madagascar is more than just a collection of rocks. It’s a living museum of geological history, a laboratory of evolution, and a powerful symbol of nature’s resilience. It reminds us that even in the planet’s harshest environments, life finds a way to carve out an existence, creating a world of breathtaking and unexpected beauty.