Mast seeding, or masting, is the intermittent, coordinated production of an enormous seed crop by a plant population. It’s a feast-or-famine strategy that plays out over vast territories, creating a living, shifting map of resource availability. Let’s explore the geography of this incredible natural rhythm.

Where Nature Draws Its Boom-and-Bust Map

Masting isn’t confined to one type of forest or continent. It’s a global strategy, and the map of its occurrences highlights some of the world’s most iconic landscapes.

The Oak and Pine Forests of North America

In the eastern United States, the great deciduous forests are masters of the mast. From the rolling hills of New England down the spine of the Appalachian Mountains, oak species (Quercus) coordinate their acorn production. In a mast year, the forest floor is literally paved with them. Further west, in the high elevations of the Rocky Mountains, keystone species like the whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) engage in the same cycle, producing massive quantities of nutrient-rich nuts that are a critical food source for wildlife, including the iconic grizzly bear.

The Beech Groves of Europe

Across the Atlantic, from the United Kingdom to the Carpathian Mountains of Poland and Romania, European beech trees (Fagus sylvatica) are the primary actors. These magnificent trees, which dominate vast tracts of forest in countries like Germany and France, will go years producing few beechnuts before suddenly, in unison, dropping a colossal crop. This event, known as a “beech mast”, historically dictated the practice of pannage, where farmers would drive their pigs into the forests to fatten up on the free bounty.

New Zealand’s Isolated Rhythms

Perhaps nowhere is masting more dramatic than in New Zealand. The nation’s unique, isolated geography has led to a finely tuned system. The sprawling tussock grasslands and the ancient southern beech (Nothofagus) forests exhibit some of the most intense and highly synchronized masting events on the planet. This boom in food has profound, and sometimes devastating, consequences for the islands’ native fauna, which evolved in this fluctuating environment.

The El Niño Connection in Borneo

In the steamy rainforests of Southeast Asia, the giant dipterocarp trees, which form the canopy of Borneo’s jungles, mast on a super-regional scale. These events are not annual; they are tied to a major global climate phenomenon: the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). The particularly dry conditions associated with a strong El Niño event act as a geographic trigger, causing entire forests across the island—spanning the countries of Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei—to flower and fruit in breathtaking synchrony.

The Secret Signals: Why Does Masting Happen?

How do trees separated by hundreds of kilometers “decide” to mast in the same year? They don’t have a conference call. Instead, they respond to a combination of internal resources and external environmental cues, driven by two primary evolutionary strategies.

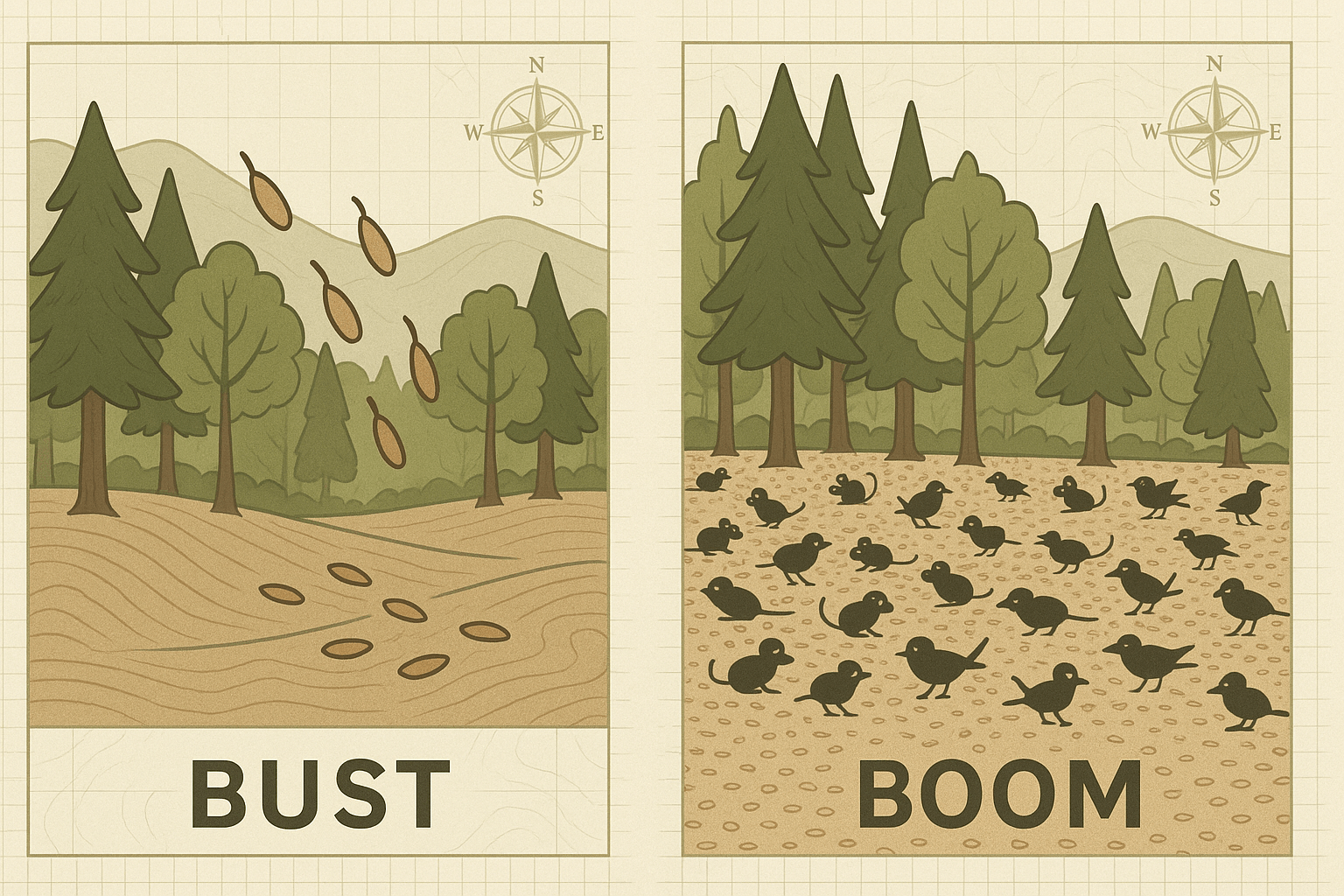

- The Predator Satiation Hypothesis: This is the most widely accepted theory. During the “bust” years of low seed production, populations of seed-eating animals (predators) like mice, squirrels, and insects are kept low due to food scarcity. Then, during a “boom” or mast year, the trees produce such an overwhelming glut of seeds that the predators simply can’t eat them all. They are satiated, and a significant number of seeds survive to germinate. It’s a brilliant strategy of winning by overwhelming numbers.

- The Pollination Efficiency Hypothesis: For wind-pollinated species like oaks and beeches, masting dramatically increases the odds of successful pollination. By releasing a massive, coordinated cloud of pollen, the trees ensure that pollen grains will find their mark, even over long distances, leading to higher fertilization rates and a more successful seed crop.

The synchronizing agent is geography itself. Trees across a region experience the same broad climatic conditions. A uniquely warm and dry spring, for example, might act as a trigger, signaling to the trees that conditions are right to invest their stored energy into a massive reproductive effort one or two years down the line. It’s the shared weather map that gets all the trees on the same page.

From Acorns to Ailments: The Cascade Effect Across the Map

A mast year doesn’t just mean more nuts. It sends powerful ripples—a trophic cascade—up and down the food chain, redrawing the ecological map of the entire region and even impacting human geography.

The most immediate effect is a population explosion of seed-eaters. Mice and vole populations can skyrocket. In Europe, wild boar numbers swell. In North America, squirrels, chipmunks, and deer thrive. This, in turn, provides a feast for their predators: owls, weasels, foxes, and coyotes see their populations rise in the following year.

But there’s a darker side to this boom, particularly for humans. In the northeastern United States, a well-documented connection exists between oak mast years and the incidence of Lyme disease. Here’s how the map of risk unfolds:

- A mast year for oaks leads to a boom in the white-footed mouse population the next summer.

- Mice are highly effective hosts for the black-legged ticks that carry the Lyme disease bacterium.

- The following spring (two years after the mast), a large population of infected tick nymphs emerges, dramatically increasing the risk of humans contracting Lyme disease in those forested areas.

This is a stunning example of how a botanical event in a forest can directly influence public health in nearby towns and cities.

A Shifting Map: Mast Seeding in a Warming World

The delicate, geographically-tuned dance of mast seeding is vulnerable to climate change. The predictable weather cues that trees have relied upon for millennia are becoming more erratic. Warmer winters, unseasonal droughts, and extreme weather events can disrupt the cycle.

This disruption could desynchronize the trees, making their predator satiation strategy less effective. In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the whitebark pine is facing a triple threat: climate change, an invasive fungus, and mountain pine beetles that are surviving warmer winters. The resulting decline in pine nuts and the increasing unpredictability of mast years directly threaten the long-term survival of the grizzly bear populations that depend on this high-fat food source to prepare for hibernation.

Mast seeding is more than a botanical curiosity. It is a powerful geographic force, a natural engine that drives the ebb and flow of life across entire biomes. It’s a reminder that from a single acorn on the forest floor to the global climate patterns that circle the planet, every part of our world is connected in a complex, shifting, and deeply fascinating map.