When we picture the future of urban life, our minds often jump to the staggering scale of megacities—teeming metropolises like Tokyo, Delhi, or São Paulo, each a world unto itself with over 10 million inhabitants. But look closer at a satellite map at night, and you’ll see something even more profound. The bright clusters of individual cities are beginning to blur, connected by luminous ribbons of highways and settlements. We are moving beyond the era of the megacity and into the age of the megaregion.

A megaregion is not just one giant city, but a large network of metropolitan areas, linked together by shared economies, infrastructure, and natural systems. They are the new engines of the global economy, the places where a disproportionate amount of the world’s innovation, wealth, and cultural production is generated. Forget thinking in terms of single cities; to understand the 21st century, we need to think on a regional scale.

From Megacity to Megaregion: A Shift in Scale

The key difference between a megacity and a megaregion is one of structure. A megacity is a single, dense urban core and its surrounding suburbs. A megaregion, on the other hand, is polycentric—it has multiple distinct urban centers that function as a single, integrated whole. Think of it less like a single star and more like a galaxy, a cluster of stars bound together by invisible forces.

These forces are what define a megaregion:

- Economic Interdependence: Cities within the region specialize. One might be a financial hub, another a tech incubator, and a third a manufacturing powerhouse, all feeding into a complex regional supply chain and labor market.

- Infrastructure Connectivity: They are bound by high-capacity transportation corridors. Superhighways, high-speed rail lines, and interlocking airport systems allow for a constant flow of people and goods.

- Shared Natural Systems: Often, these regions develop along powerful geographic features like a coastline, a river delta, or a valley. They share watersheds, air basins, and coastal ecosystems, making environmental challenges a regional concern.

- Cultural Linkages: Over time, these regions develop a sense of shared identity, with residents frequently traveling between cities for work, leisure, and family.

A Tour of the World’s Emerging Megaregions

While the concept is global, megaregions are shaped by their unique local geography. Let’s take a tour of some of the most prominent examples.

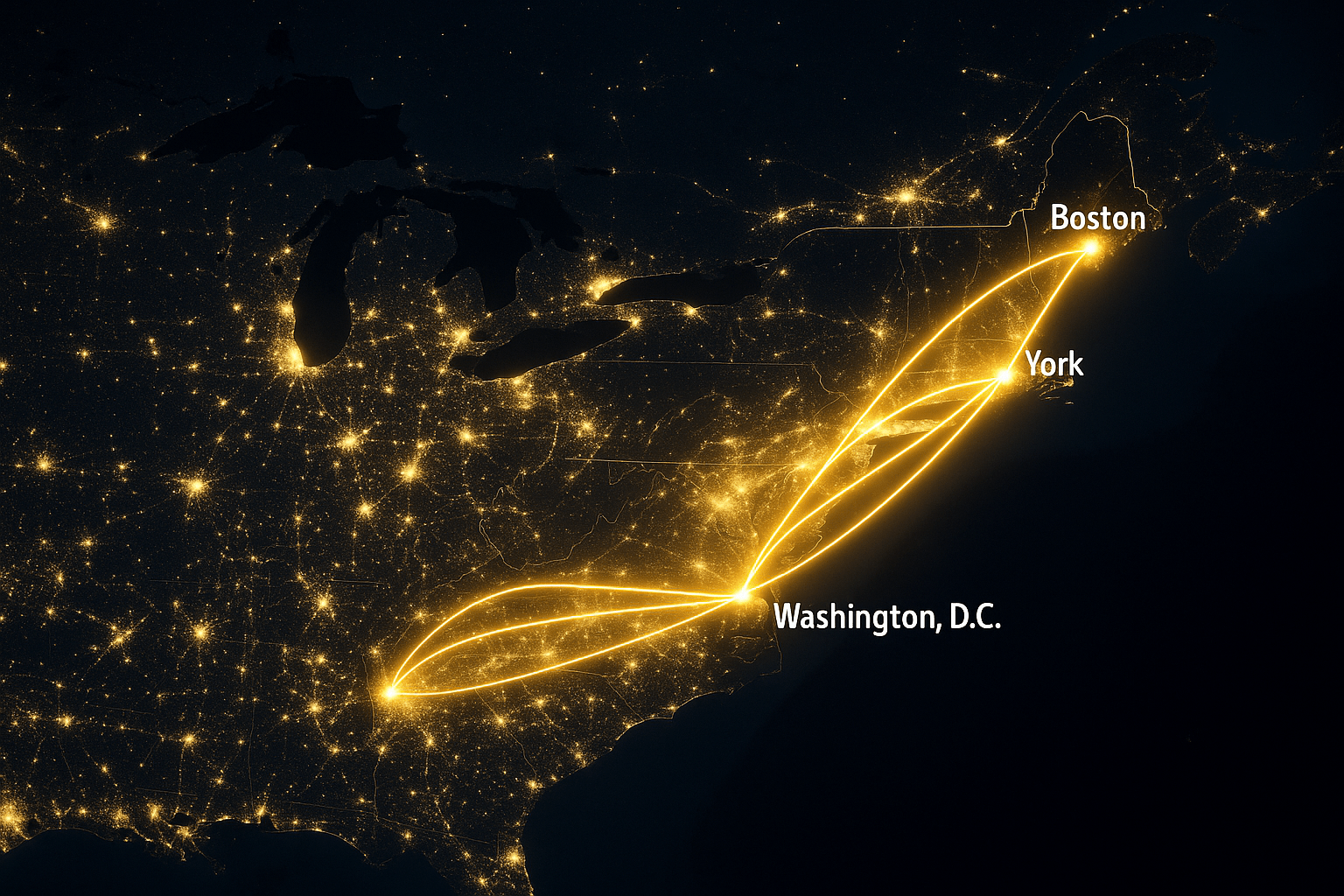

The Original: “Bos-Wash” (Northeast Megalopolis, USA)

Coined by geographer Jean Gottmann in 1961, the Northeast Megalopolis is the classic example. Stretching roughly 500 miles along the Atlantic coast from Boston down to Washington, D.C., it includes New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. This region, home to over 50 million people, sits on a relatively flat coastal plain, which made building the connecting infrastructure—the I-95 highway and the Amtrak rail corridor—geographically straightforward. Today, it’s a global powerhouse of finance (Wall Street), politics (D.C.), education (the Ivy League), and biotechnology.

The Manufacturing Powerhouse: The Pearl River Delta (Greater Bay Area, China)

Perhaps the most dynamic megaregion today, the Pearl River Delta is an immense urban cluster built around the estuary where the Pearl River meets the South China Sea. This low-lying, water-rich delta geography is perfect for port development. It links the global financial hub of Hong Kong with the tech and innovation giant of Shenzhen and the manufacturing capital of Guangzhou. With staggering infrastructure projects like the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge and an ever-expanding high-speed rail network, the region functions as a hyper-efficient ecosystem for producing and exporting goods to the entire world.

The European Core: The “Blue Banana”

This isn’t a single country, but a crescent of urbanized prosperity curving from Southeast England through the Benelux countries, Western Germany, and Switzerland, down into Northern Italy. It’s less a contiguous urban strip and more a dense network of powerful cities like London, Amsterdam, Brussels, Frankfurt, and Milan. Its geography follows the historical trade routes along the Rhine River valley. It represents the economic and political heartland of the European Union, a post-industrial landscape defined by finance, logistics, and high-tech industry.

Other major global players include Japan’s Taiheiyō Belt (from Tokyo to Osaka) and North America’s Great Lakes Megaregion (linking Chicago, Detroit, and Toronto across an international border).

The Geographical Glue: What Holds a Megaregion Together?

Megaregions don’t form randomly. They are a product of the interplay between physical and human geography.

Physical geography provides the foundation. As seen with Bos-Wash and the Pearl River Delta, coastlines and river systems offer natural corridors for transportation and trade, which have been hubs of human settlement for millennia. These features facilitate the initial growth that allows cities to eventually connect.

But it’s human geography that provides the “glue.” The most critical element is infrastructure. High-speed rail is a game-changer, turning a 3-hour drive into a 1-hour train ride, effectively shrinking the region and making daily inter-city commuting feasible. The Channel Tunnel, for instance, functionally links London to the Blue Banana. Likewise, massive port complexes and hub airports don’t just serve one city; they serve the entire region’s economic needs.

This connectivity fosters economic complementarity. Instead of competing, cities specialize. In the Great Lakes, for example, Chicago is the financial and logistics hub, while surrounding cities focus on advanced manufacturing and automotive research. This creates a resilient, diversified regional economy greater than the sum of its parts.

The Challenges of a Megaregional Future

The rise of megaregions is not without significant problems. Their immense scale presents unprecedented challenges.

- Governance: How do you plan for a region that crosses multiple city, state, and sometimes even national borders? Coordinating transportation, housing, and economic policy becomes a tangled bureaucratic web.

- Inequality: These regions concentrate immense wealth, often exacerbating economic divides between the megaregion and the rest of the country. Within the region itself, soaring housing costs can push out lower-income residents, creating deep pockets of poverty alongside extreme wealth.

- Sustainability: The environmental footprint is colossal. Managing water resources, air quality, waste disposal, and energy consumption for 50+ million people in a single integrated system is one of the greatest sustainability challenges of our time.

Conclusion: The Inevitable Rise of the Megaregion

Whether we plan for them or not, megaregions are the functional reality of our globalized world. They are the crucibles of innovation, the nodes of global trade, and the magnets for human talent. They have superseded individual cities as the most important unit of economic and social life on the planet.

Looking at a map, we still see the old lines of cities, states, and nations. But to truly understand the geography of human settlement in the 21st century, we must learn to see the new connections—the powerful, sprawling, and complex urban ecosystems that are defining our future.