A Valley of Lakes: The Physical Geography of Tenochtitlan

To understand the genius of the chinampas, we must first understand the unique landscape the Aztecs called home. The Valley of Mexico is a high-altitude basin, sitting at over 2,200 meters (7,200 feet) above sea level. Geologically, it’s an endorheic basin, meaning it has no natural drainage outlet. For millennia, rainfall and snowmelt from the surrounding mountains collected in the valley floor, forming a series of five interconnected, shallow lakes: Zumpango, Xaltocan, Texcoco, Chalco, and Xochimilco.

Lake Texcoco, the largest, was brackish, while the southern lakes of Chalco and Xochimilco were fed by freshwater springs, creating a more hospitable environment for life. It was upon an island in Lake Texcoco that the Aztecs, or Mexica, founded their magnificent capital, Tenochtitlan, in the 14th century. But this watery world presented a monumental challenge: how do you support a burgeoning population, which would eventually reach an estimated 200,000 people, on swampy, unstable, and often saline land? The answer lay in reshaping the very geography of the lake itself.

Engineering an Agricultural Miracle: The Chinampa System

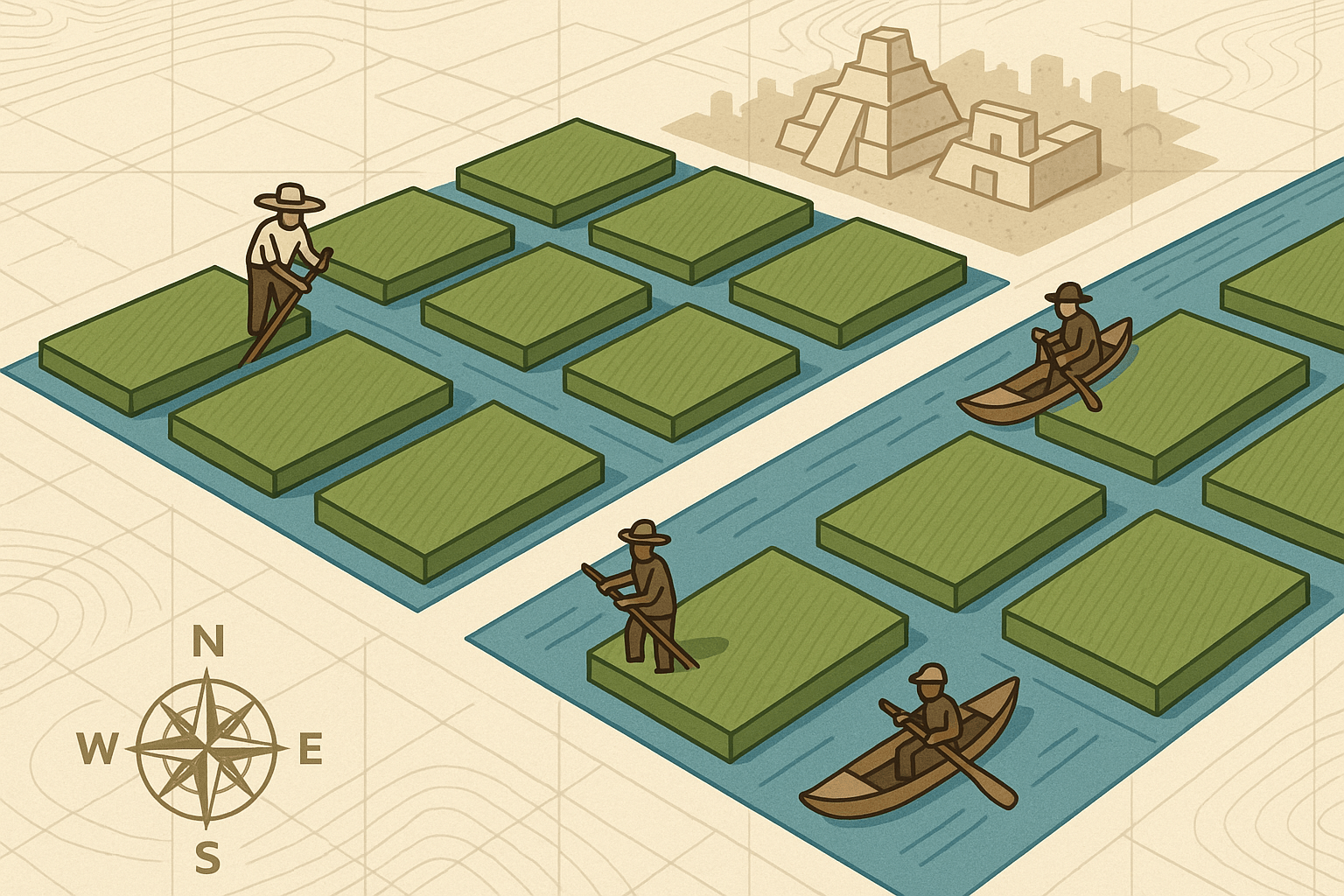

The term “floating gardens” is a romantic misnomer. Chinampas don’t actually float. They are, in fact, remarkably stable, man-made agricultural plots built up from the lakebed—a masterclass in human-environment interaction. This fusion of hydroponics and land reclamation was a technology perfected by the Aztecs, allowing them to create some of the most intensely fertile and productive farmland in the ancient world.

The construction was a brilliant, labor-intensive process rooted in a deep understanding of the local ecosystem:

- Layout and Foundation: First, the farmers would use stakes to mark out a rectangular plot in the shallow lake, typically about 30 meters long and 2.5 meters wide. These plots were woven together with reeds and branches to form a sturdy fence.

- Building the Island: The enclosed area was then meticulously filled with layers of mud and sediment dredged from the bottom of the canals, alternated with layers of decaying vegetation and aquatic weeds. This created an incredibly rich, nutrient-dense soil bed that rose about a meter above the water level.

- Anchoring with Life: The true genius lay in the final step. The Aztecs planted native ahuejote (willow) trees at the corners and along the edges of the new island. The extensive root systems of these willows would anchor the chinampa firmly to the lakebed, prevent erosion, and provide shade.

The canals that formed between each chinampa were as important as the islands themselves. They served as transportation corridors for canoes, allowing farmers to easily move produce to the city’s markets. More importantly, the canals provided a constant, passive irrigation system. Water would seep through the porous walls of the chinampa, keeping the soil perpetually moist without ever becoming waterlogged. The farmers would also scoop nutrient-rich mud from the bottom of the canals to continuously replenish the soil’s fertility.

Feeding an Empire: The Human Geography of Abundance

The chinampa system was the engine that powered the Aztec Empire. This incredibly efficient form of agriculture allowed for up to seven different harvests per year. While the rest of Mesoamerica depended on seasonal rains and often managed only one or two corn harvests, the chinamperos of Xochimilco and Chalco were cultivating year-round.

This immense agricultural surplus was the foundation of Aztec society. It fed the vast population of Tenochtitlan, freeing up a large portion of the populace to become the priests, warriors, artisans, and administrators who built and ran the empire. The chinampas yielded a bounty of crops essential to the Aztec diet: maize, beans, squash (the “Three Sisters”), amaranth, tomatoes, and chilies. But they were also famous for their flowers—the very name Xochimilco means “place of the flower field” in the Nahuatl language. Flowers were central to Aztec religious ceremonies, and the vibrant blooms of the chinampas were a vital part of the capital’s cultural and spiritual life.

This system represents one of history’s most successful examples of sustainable, intensive agriculture. The Aztecs didn’t just adapt to their environment; they actively engineered it to create a symbiotic relationship between their city and the lake that surrounded it.

Xochimilco Today: A Living Relic Facing Modern Threats

After the Spanish conquest, the new rulers saw the lakes not as a resource but as a threat. Obsessed with controlling perennial flooding and imposing a European urban model, they began the centuries-long process of draining the Valley of Mexico’s lakes. Today, only a fraction of the original lake system survives, almost entirely within the canals of Xochimilco.

What was once a vast agricultural zone is now a beloved, and vital, recreational area. The canals are famous for the colorful, flat-bottomed boats called trajineras, which pole visitors through the waterways, often accompanied by floating mariachi bands and food vendors. This cultural tourism provides a crucial economic lifeline to the region.

Yet, this UNESCO World Heritage site faces grave geographical and ecological challenges. The insatiable thirst of modern Mexico City has led to the over-extraction of water from the underlying aquifer, causing the entire region, including the chinampas, to sink and dry out. Urban sprawl constantly encroaches on the agricultural zone, and pollution from city runoff contaminates the water, threatening the delicate ecosystem. Invasive species like carp and tilapia, introduced decades ago, have decimated native fauna, including the iconic and critically endangered Axolotl, a salamander that lives its entire life in water.

Xochimilco is therefore at a crossroads. It is a portal to Mexico City’s aquatic past and a stunning example of Aztec ingenuity. But it is also a fragile ecosystem buckling under the pressures of the modern megacity it helped create. The floating gardens of Xochimilco are more than just a beautiful day trip; they are a living lesson in geography, a reminder that the relationship between humans and their environment is a story of creation, sustenance, and, all too often, consequence.