When we picture the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), images of fighter jets, naval fleets, and soldiers in multinational exercises often come to mind. It’s an alliance built on military might and collective defense, a geopolitical heavyweight spanning from North America to the heart of Europe and beyond. But behind the hardware and the high-stakes strategy lies a less visible but equally crucial foundation: language. NATO is not just a military alliance; it is a remarkably complex and successful linguistic one, held together by two official languages and the immense effort required to bridge the gap between dozens more.

A Tale of Two Tongues: Why English and French?

From its inception in 1949, NATO established English and French as its two official languages. This was not an arbitrary choice but a reflection of the Alliance’s founding geography and political reality. The original twelve signatories included key Anglophone and Francophone powers whose influence shaped the early organization.

- English: The dominant language of the United States and the United Kingdom, the two primary military and economic powers behind the treaty’s creation. Canada, another founding member, is also bilingual, further cementing the importance of English.

- French: The language of France, a continental European power central to the post-war security architecture. It was also the official language of Belgium, the host country for NATO’s political headquarters, and a co-official language in Canada and Luxembourg. Historically, French was the preeminent language of diplomacy (the lingua franca), lending it significant prestige and practicality.

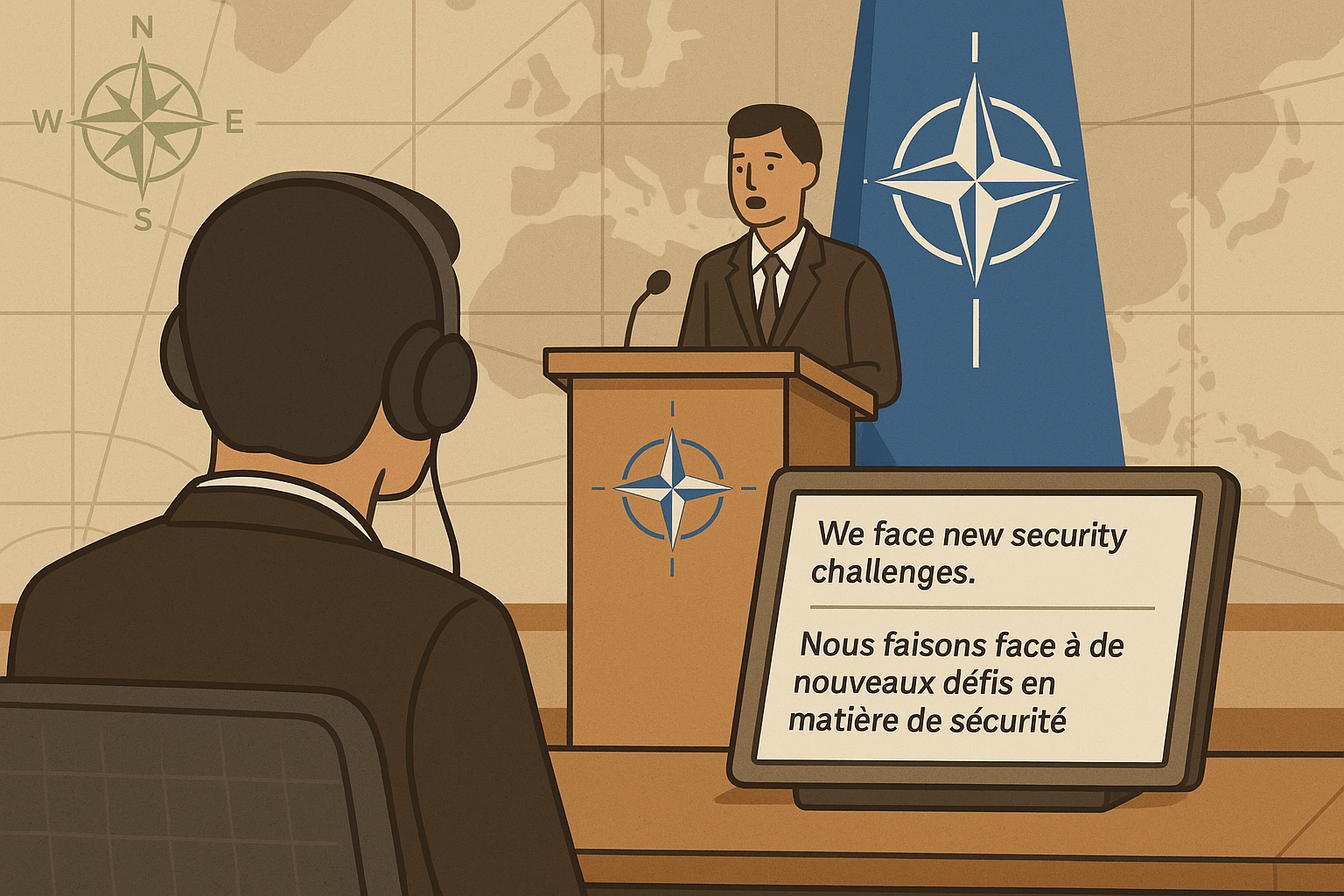

Every official document, every press release, and every statement from the Secretary General is produced simultaneously in both English and French. In any meeting, a representative from any member state can speak in either language, with simultaneous interpretation provided. This bilingual policy is enshrined in the very fabric of the Alliance, a constant nod to its transatlantic origins.

The Linguistic Map of a Modern Alliance

While English and French provide the operational framework, the true linguistic geography of NATO is a vibrant mosaic reflecting its expansion over seven decades. From the original 12 members, the Alliance has grown to 32 countries, each bringing its own language, culture, and perspective. A flyover of the Alliance reveals an incredible diversity of language families:

- Germanic Languages: Beyond English, this group includes German, Dutch (in the Netherlands and Belgium), Norwegian, Danish, and Icelandic.

- Romance Languages: French is joined by Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and Romanian, showcasing the family’s spread from the Iberian Peninsula to the Black Sea.

- Slavic Languages: NATO’s eastward expansion after the Cold War brought in a host of Slavic tongues, including Polish, Czech, Slovak, Bulgarian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Slovenian.

- Baltic Languages: The accession of Latvia and Lithuania introduced the two surviving languages of this unique Indo-European branch.

- Finno-Ugric Languages: This distinct family is represented by Estonian, Hungarian, and most recently, Finnish.

And the list goes on, including Greek (Hellenic branch), Turkish (a Turkic language), and Albanian. This means that a single meeting of the North Atlantic Council—NATO’s principal political decision-making body—could have representatives who think and natively speak in over two dozen different languages. It’s a human geography challenge of epic proportions, managed daily in the heart of Europe.

Brussels and Mons: The Bilingual Heart of NATO

It is fitting that NATO’s headquarters are located in a country that embodies linguistic complexity. Brussels, the home of NATO’s political HQ, is the officially bilingual capital of Belgium, a city where French and Dutch (Flemish) coexist. Just 50 kilometers south lies Mons, home to the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE), NATO’s strategic military command.

Inside these hubs, English and French are the active working languages. Corridors buzz with conversations that switch seamlessly between the two. Staff are typically required to be proficient in one and have a working knowledge of the other. This creates a unique microcosm where a Polish officer might brief a Turkish diplomat in English, who then clarifies a point with a French colleague in French. This constant linguistic negotiation is central to the Alliance’s culture of consensus and cooperation.

In the Heat of the Moment: The Interpreter’s Gauntlet

The true test of NATO’s linguistic system comes during a crisis. Imagine a scenario: a hybrid attack is detected near the Suwałki Gap, a strategic sliver of land on the Polish-Lithuanian border. The North Atlantic Council convenes an emergency session. The Polish ambassador, speaking French, provides a rapid-fire update. The German general at SHAPE, patched in via video link, gives a military assessment in English. The Italian Prime Minister asks a follow-up question.

In soundproof booths, teams of simultaneous interpreters perform a breathtaking mental feat. They don’t just translate words; they translate meaning, nuance, and urgency. They must be masters of highly technical military and political jargon in multiple languages. A mistranslation of “rules of engagement” or “a limited incursion” could have catastrophic consequences. These interpreters are the unseen, unsung linchpins of Alliance cohesion. They ensure that when a decision must be made in minutes, language is a bridge, not a barrier.

This real-time translation is a crucial element of NATO’s “interoperability”—its ability for forces from different nations to work together effectively. While standardizing ammunition and communication equipment is vital, standardizing understanding is paramount.

Unifying the Airwaves: The NATO Phonetic Alphabet

Beyond formal meetings, NATO has developed practical tools to cut through the fog of language on the battlefield. The most famous of these is the NATO phonetic alphabet: Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta…

Developed to be understandable and clearly distinguishable to any listener, regardless of their native language or the quality of the radio signal, this alphabet is a masterpiece of linguistic design. Whether you’re a Finnish pilot, a Portuguese sailor, or an American soldier, “Victor” sounds distinct from “Bravo.” It ensures that critical information, like coordinates or call signs, is transmitted with absolute clarity. It’s a simple, elegant solution to the complex geographical and linguistic reality of a multinational military force in action.

NATO’s strength ultimately lies not just in its shared arsenal, but in its shared understanding. The commitment to its two official languages, the incredible skill of its interpreters, and the practical tools developed for the field all serve one purpose: to ensure that 32 nations, speaking dozens of tongues, can act with one voice and one purpose when it matters most. It is a daily testament to the idea that with dedication and structure, a multitude of voices can achieve remarkable harmony.