A Land Forged by Ice

To understand Fiordland, you must travel back in time to the Ice Ages. During these periods, vast rivers of ice, some several kilometres thick, accumulated in the Southern Alps and began to flow, driven by gravity, towards the Tasman Sea. These weren’t the gentle rivers we know today; they were immense conveyors of rock and ice, relentlessly scouring the earth beneath them.

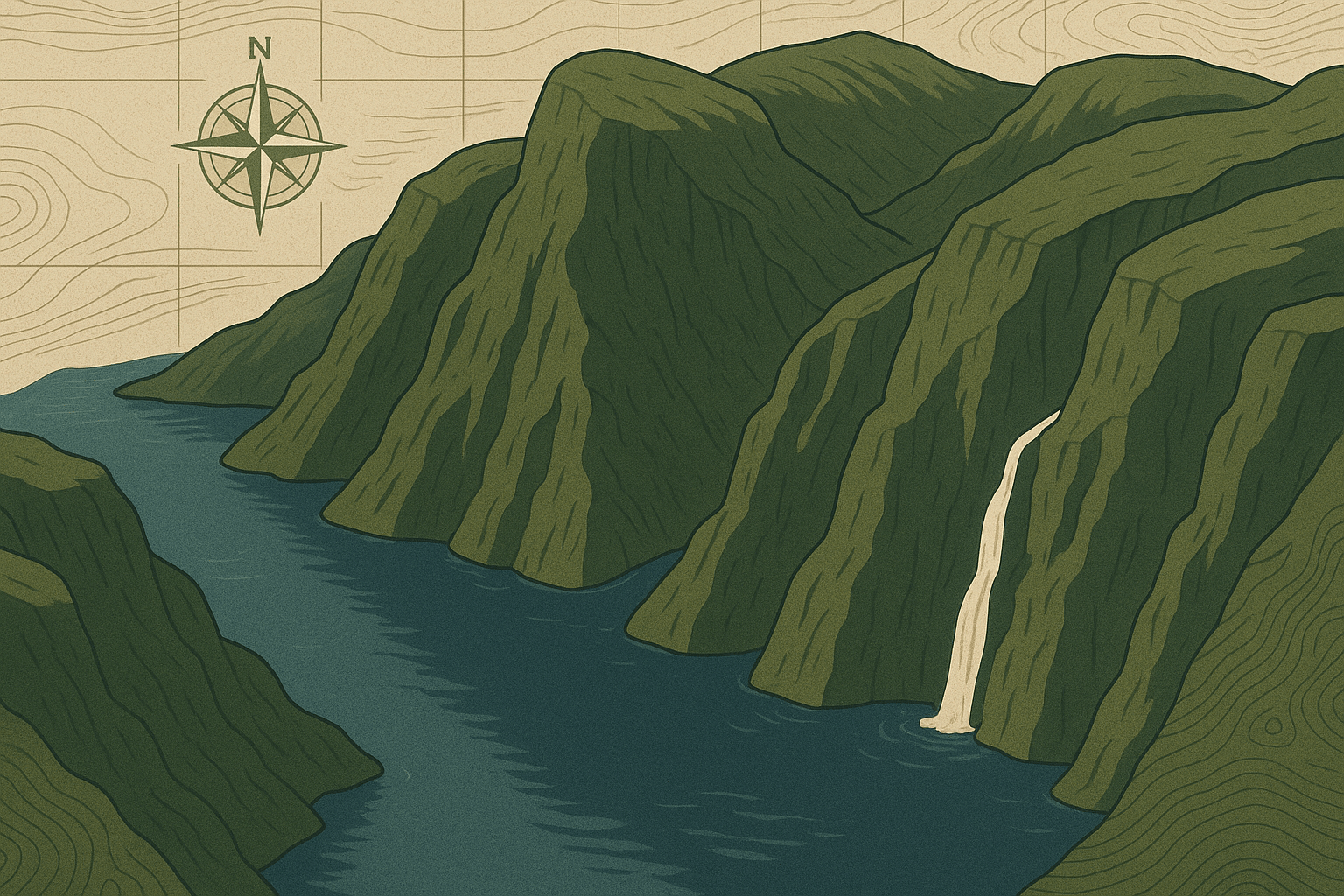

Before the ice, the region was characterized by typical V-shaped river valleys. But as the glaciers advanced, they acted like cosmic-scale chisels. They plucked massive boulders from the valley walls and used this debris as a powerful abrasive, grinding away at the bedrock. They straightened sharp corners, deepened the valley floors, and steepened their sides, transforming the ‘V’ shape into the classic, deep U-shaped valley that is the hallmark of glacial carving. The scale is almost incomprehensible; these glaciers carved valleys that now sit more than 400 metres below sea level.

The Anatomy of a Fiord

What exactly is a fiord? The definition is crucial: a fiord is a long, deep, narrow sea inlet formed when a U-shaped valley, carved by a glacier, is “drowned” by the sea after the glacier retreats. When the last Ice Age ended and global temperatures rose, two things happened: the massive glaciers melted and retreated back up into the mountains, and sea levels rose dramatically. The ocean flooded into these immense, newly-carved trenches, creating the fiords we see today.

Fiordland’s geography is characterized by several key features:

- Hanging Valleys and Waterfalls: The main, most powerful glaciers carved the deepest valleys. Smaller, tributary glaciers flowing from adjacent valleys had less erosive power and couldn’t carve as deep. When the ice all melted, these smaller valleys were left “hanging” high above the main fiord floor. Today, rivers and streams cascade from these hanging valleys, creating the hundreds of spectacular, permanent and temporary waterfalls for which Fiordland is famous, like Stirling Falls and Bowen Falls in Milford Sound.

- Incredible Depth: The fiords are profoundly deep. Doubtful Sound, for instance, reaches a depth of 421 meters (1,381 feet), while the surrounding mountains soar to over 1,700 meters (5,500 feet). This vertical relief from mountain peak to fiord floor is one of the most dramatic on the planet.

- Terminal Moraine Sills: As a glacier scrapes along, it pushes a huge pile of rock and debris at its front, known as a terminal moraine. When the glacier reached the sea and began to melt, it dropped this massive pile of rubble at the mouth of the valley. This underwater ridge, or “sill”, makes the entrance to many fiords much shallower than their interior. This feature has a profound impact on the fiord’s ecosystem.

A World in Isolation: Fiordland’s Unique Ecosystems

The extreme geography directly creates one of the world’s most unusual marine environments. Fiordland is one of the wettest places on Earth, receiving up to 7 meters (23 feet) of rain per year. This immense volume of freshwater runs off the steep, forested cliffs and settles on top of the dense, salty seawater in the fiords.

This top layer of fresh water, often several metres thick, is stained dark brown by tannins from the forest floor. This dark layer acts like a massive light filter, blocking sunlight from penetrating the saltwater below. The result is a phenomenon called “deep-water emergence”, where light-sensitive creatures that would normally only live in the crushing pressures of the abyssal deep can thrive in much shallower water. In Fiordland, you can see fragile, beautiful black coral trees at depths of just 10 meters, a habitat that would typically begin at 100 meters or more. The fiords are a living laboratory, an accessible glimpse into the deep ocean.

On land, the sheer cliffs and impenetrable rainforest created pockets of isolation, allowing unique flora and fauna to evolve. This rugged terrain served as a natural fortress for New Zealand’s flightless birds, providing one of the last mainland refuges for species like the critically endangered Kakapo (night parrot) and the Takahe, a bird thought to be extinct for 50 years before its rediscovery in a remote Fiordland valley.

The Human Footprint in a Giant’s Realm

Fiordland’s geography has always dictated the terms of human interaction. For early Māori, the fiords (known as Ata Whenua – Shadowlands) were a vital source of food and precious pounamu (greenstone), but they were places of seasonal passage, not permanent settlement. The sheer verticality and torrential rain made large-scale habitation impossible.

Today, the park remains virtually uninhabited. The “towns” associated with it, Te Anau and Manapouri, are gateways that lie on its eastern edge. The famous Milford Sound is not a town but a small, specialized tourism hub with a wharf, an airstrip, and visitor facilities. The very geography that repelled settlement is now the primary draw for over a million visitors a year.

Even accessing the heart of Fiordland is a geographical challenge. The Milford Road, completed in 1953, is an engineering marvel that clings to mountainsides and culminates in the Homer Tunnel, a 1.2km passage drilled through a solid wall of granite. To reach the even more remote Doubtful Sound, visitors must take a boat across Lake Manapouri and then a bus over the dramatic Wilmot Pass—the only way to experience its profound scale and silence.

A Landscape of Living Geography

From the U-shaped profile of Milford Sound’s valley to the tannin-stained waters that hide deep-sea life, Fiordland is a masterclass in physical geography. It’s a place where the forces that shape our planet are not abstract concepts from a textbook but are visible in every cliff face, every waterfall, and every silent, deep waterway. It is a powerful reminder that we are small figures in a landscape carved by giants, a raw and magnificent corner of the world still ruled by the power of ice and water.