The Yellowstone Effect: How Wolves Re-engineered a Landscape

Perhaps the most iconic rewilding story unfolded in the vast expanse of Yellowstone National Park, USA. In 1995, after a 70-year absence, grey wolves were reintroduced to the park. The goal was to restore a missing predator, but the results cascaded through the entire ecosystem, physically altering the geography of the park in a process known as a trophic cascade.

Before the wolves, the elk population had ballooned. They grazed unchecked along the park’s riverbanks, devouring young willows and aspen trees. The riverbanks became bare and eroded. When the wolves returned, they did what wolves do: they hunted elk. But they also changed the elks’ behaviour. Fearing ambush, the elk avoided valleys and gorges, allowing the vegetation to rebound. As willows and aspens flourished, they stabilized the riverbanks. This had a stunning geographical consequence: the rivers began to meander less, their channels narrowed and deepened, and pools formed. The very hydrology of the park was transformed.

This cascade didn’t stop at the water’s edge. The revitalized vegetation brought back songbirds. The new beaver populations, with ample wood for their dams, created marshes and ponds, which in turn provided habitats for otters, muskrats, and amphibians. The wolf kills provided food for scavengers like bears and eagles. From a human geography perspective, the reintroduction sparked intense debate with local ranchers over livestock predation but also fueled a massive boom in ecotourism, with visitors flocking from around the globe, eager to hear a wolf’s howl echo across the Lamar Valley.

Britain’s Unlikely Engineers: The Beaver Comeback

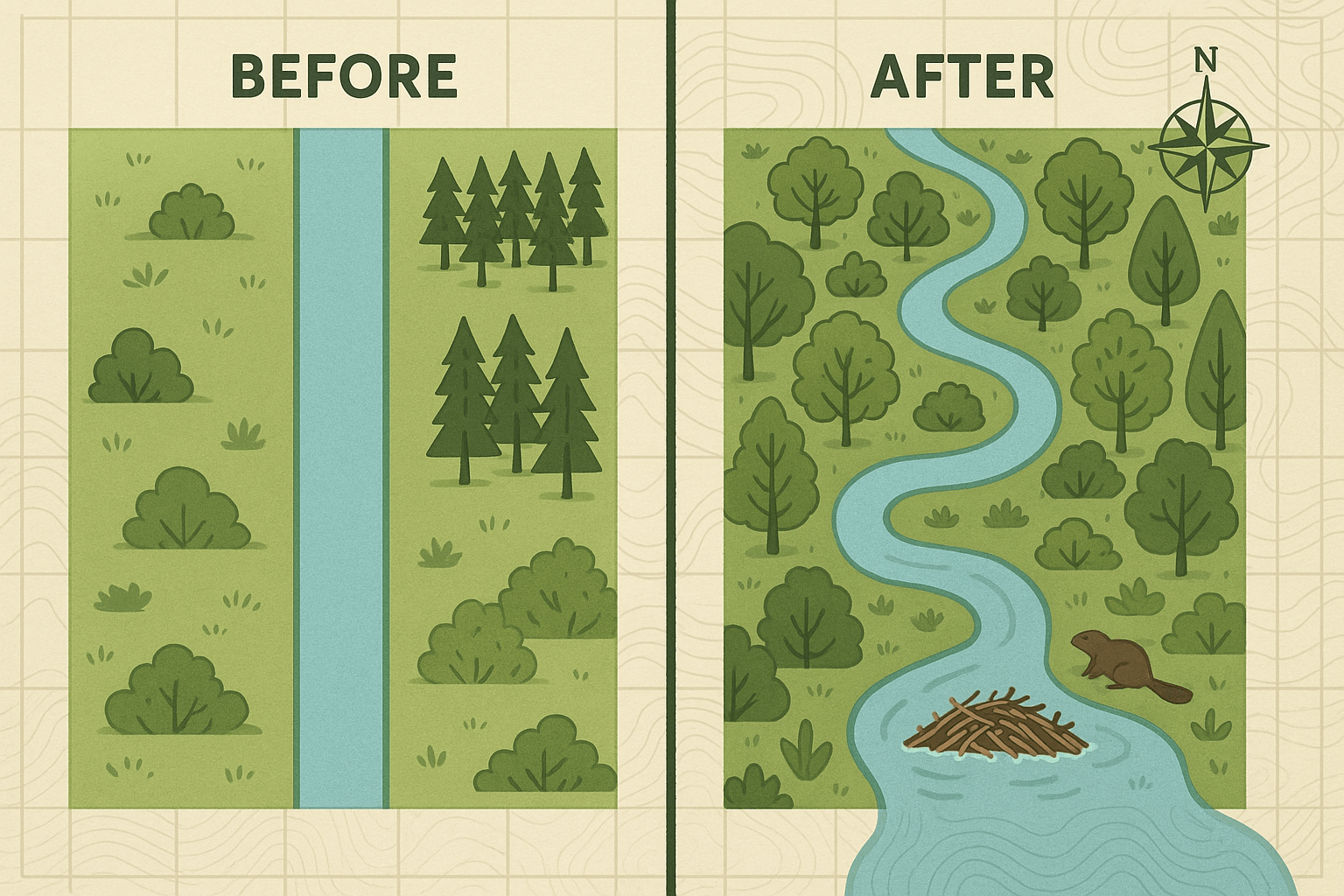

Across the Atlantic, a much smaller, but no less significant, engineer has been put back to work. Beavers, hunted to extinction in Britain 400 years ago, are being reintroduced in controlled projects from the River Otter in Devon to the forests of Knapdale, Scotland. Their impact on the British landscape, particularly its hydrology, is revolutionary.

Beavers are nature’s water managers. Their dams create intricate networks of ponds and wetlands in a landscape long drained for agriculture. This has several profound geographical benefits:

- Flood Mitigation: In a country increasingly battered by extreme rainfall, beaver dams act as natural sponges. They slow the flow of water during storms, holding it back and releasing it slowly, dramatically reducing the risk of flash flooding in towns and villages downstream.

- Drought Resilience: The wetlands created by beavers store water on the landscape, recharging groundwater supplies and maintaining streamflow during dry periods.

- Water Purification: The dams trap sediment and pollutants, filtering the water and improving its quality for everything and everyone downstream.

Of course, this re-engineering is not without human-geographical conflict. The beavers’ work can flood valuable farmland, leading to friction with agricultural communities. This has forced a rethink of land use and prompted new strategies for coexistence, illustrating how rewilding necessitates not just ecological change, but social and political adaptation as well.

A Dutch Experiment: The Oostvaardersplassen

Not all rewilding projects involve reintroducing historically native species. In the Netherlands, on a polder—land reclaimed from the sea in the 1960s—lies one of the most ambitious and debated rewilding sites in the world: the Oostvaardersplassen.

Here, in one of the most densely populated countries on Earth, scientists attempted to create a self-regulating, Paleolithic-style ecosystem. Since the original megafauna like aurochs and tarpan were extinct, they introduced proxies: Heck cattle, Konik horses, and red deer. The idea was to let these large herbivores shape the landscape without human interference.

The physical geography that emerged was a unique mosaic of open grasslands and wetlands, dictated entirely by grazing pressure. However, the project’s “hands-off” approach collided with human geography. Without large predators to control their numbers, the grazer populations boomed and crashed, leading to mass starvation during harsh winters. This spectacle, visible to the public, sparked fierce ethical debates about animal welfare and the definition of “wild” in a profoundly human-managed landscape. The Oostvaardersplassen serves as a powerful, cautionary tale about the complexities of rewilding in close proximity to human settlement.

The Next Frontier: Rewilding at a Continental Scale

These isolated projects are inspiring, but the future of rewilding lies in connection. For ecosystems to be truly resilient, especially in the face of climate change, they can’t be islands. This has given rise to the concept of wildlife corridors—vast networks designed to connect protected areas, allowing species to move, migrate, and adapt.

Ambitious projects are already underway. The Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y) aims to connect the Rocky Mountain ecosystem across 3,400 kilometres and two countries. In Europe, the former “Iron Curtain”—a no-man’s-land of fences and watchtowers—has inadvertently become a thriving wildlife haven, now being formally protected as the European Green Belt.

This is where rewilding becomes an immense challenge of human geography. These corridors must traverse a complex patchwork of private ranches, public lands, highways, cities, and international borders. Success requires intricate land-use planning, negotiating with landowners, building wildlife overpasses over busy motorways, and fostering a culture of coexistence. It is a geographical puzzle on a continental scale.

Rewilding is more than reintroducing animals. It is a conscious decision to re-engage with the dynamic forces that shape our world. It’s about letting rivers carve new paths, allowing wetlands to re-emerge, and weaving wildness back into the fabric of our landscapes. It challenges us to see the planet not as a static map to be managed, but as a living, breathing system that we have the power—and perhaps the responsibility—to help heal.