As global warming accelerates the melting of polar ice, this shipping lane along Russia’s Arctic coast is becoming increasingly navigable. It represents a tantalizing shortcut between Europe and Asia, but it’s also a testament to Russia’s unique geographical position and its decades-long investment in mastering one of the world’s harshest environments.

Charting the Course: A Geographical Primer

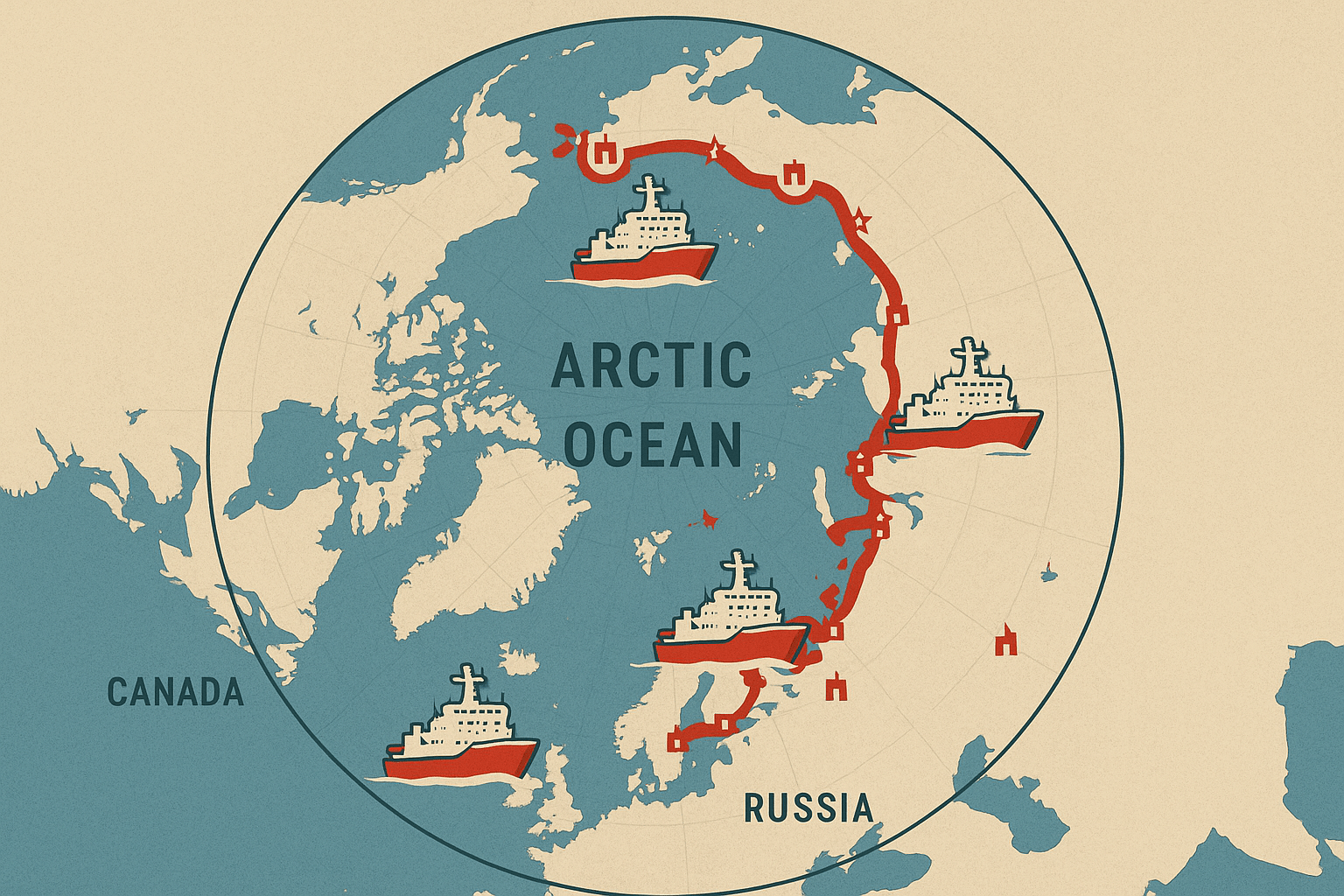

The Northern Sea Route isn’t a single, fixed line on a map. It’s a series of shipping lanes that hug the Eurasian continent, stretching approximately 5,600 kilometers (3,500 miles) from the Kara Gates strait near the Novaya Zemlya archipelago in the west, to the Bering Strait between Russia and Alaska in the east. Navigating it means traversing a succession of Arctic seas: the Kara, Laptev, East Siberian, and Chukchi Seas.

Its primary geographical advantage is distance. A voyage from Rotterdam, Europe’s largest port, to Yokohama in Japan via the traditional Suez Canal route covers over 21,000 kilometers. The same journey via the NSR is roughly 13,000 kilometers, potentially cutting travel time by 10-15 days. This reduction saves not only time but also significant fuel costs and avoids the security risks and congestion of chokepoints like the Suez Canal or the Strait of Malacca.

However, the physical geography presents immense challenges. For much of the year, thick, dynamic sea ice makes passage impossible without assistance. Weather is extreme and unpredictable, with blinding fog, fierce storms, and the disorienting phenomena of the polar night in winter and the 24-hour midnight sun in summer. The coastline is sparsely populated, and safe harbors are few and far between.

Russia’s Arctic Dominion: Infrastructure and Icebreakers

While the melting ice is a product of a global phenomenon, the ability to exploit the NSR is almost exclusively a Russian enterprise. This dominance is built on two pillars: a unique fleet of icebreakers and a strategic network of coastal infrastructure.

The Icebreaker Imperium

Russia is the only country in the world that operates a fleet of nuclear-powered icebreakers. Managed by the state-owned company Rosatomflot, these behemoths are the key that unlocks the Arctic. Vessels like the Arktika-class icebreakers can smash through ice up to three meters thick, carving paths for conventional cargo ships to follow. Without them, year-round navigation would be a fantasy.

Moscow is doubling down on this advantage, building even larger and more powerful ships. The new Lider-class icebreakers, currently under construction, are designed to be able to clear a path 50 meters wide through ice four meters thick, enabling passage for massive container ships and LNG tankers year-round. This technological supremacy gives Russia de facto control over who uses the route, when, and how.

The Human Geography of the Coastline

For centuries, Russia’s Arctic coast was a desolate, sparsely inhabited frontier. Today, it’s being transformed into a logistical backbone for the NSR. Key port cities form a strategic chain along this immense coastline:

- Murmansk: Located on the Barents Sea, this is the largest city north of the Arctic Circle and the headquarters of the icebreaker fleet. Crucially, thanks to the warm currents of the North Atlantic Drift, it is an ice-free port year-round, making it the perfect western gateway to the NSR.

- Sabetta: A city that barely existed a decade ago. Built from scratch on the Yamal Peninsula, Sabetta is a staggering example of human engineering in the Arctic. It serves the massive Yamal LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) project, and its state-of-the-art port is a primary hub for exporting Russia’s vast natural gas reserves to both Europe and Asia.

- Dudinka: Situated on the Yenisey River, this port is the outlet for the industrial city of Norilsk, home to Norilsk Nickel, the world’s largest producer of palladium and high-grade nickel. The NSR is its lifeline to global markets.

Alongside these ports, Russia maintains a network of polar weather stations, communication systems, and search-and-rescue centers, further cementing its control and making navigation safer for those willing to pay the required transit fees and accept Russian escort.

The Geopolitics of a Thawing Ocean

Russia’s control over the NSR is not universally accepted. The route’s growing importance has placed it at the center of a complex geopolitical chessboard.

Moscow legally defines the NSR as part of its internal waters, citing Article 234 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which grants coastal states special authority to enact environmental protection laws in ice-covered areas. This allows Russia to mandate permits, fees, and Russian pilotage for foreign vessels. Other maritime powers, notably the United States, contest this, arguing that major parts of the route are international straits where the principle of “freedom of navigation” should apply.

Meanwhile, other nations are keen to get involved. China has declared itself a “near-Arctic state” and is a major partner for Russia, incorporating the NSR into its global “Polar Silk Road” initiative. Chinese shipping giant COSCO is one of the most frequent foreign users of the route. For Beijing, the NSR offers a faster, more secure route for its goods and a way to access Arctic resources, aligning its interests closely with Moscow’s.

An Uncertain Future: Promise and Peril

The Northern Sea Route is no longer a distant possibility; it is a functioning, growing artery of commerce and a pillar of Russian strategic policy. It is a powerful illustration of how physical geography—in this case, climate change—can redraw maps of global power and trade.

Yet, its future is far from certain. The economic case still faces hurdles: transit fees are high, specialized ice-class vessels are expensive, and the navigation season, while lengthening, remains unpredictable. Furthermore, the environmental risks are immense. An oil spill or accident in the pristine but fragile Arctic ecosystem would be catastrophic and nearly impossible to clean up. Increased shipping also brings black carbon emissions, which settle on the ice and snow, accelerating melting in a dangerous feedback loop.

The Northern Sea Route remains a place of profound contrasts: a symbol of international opportunity wrapped in fierce national control, a product of environmental crisis that poses new environmental threats, and a modern commercial highway running through one of Earth’s last great wildernesses.