Imagine standing in a vast, white expanse, a landscape so cold the air feels sharp in your lungs. You might picture a perfectly smooth, flat sheet of snow stretching to the horizon. But in the Earth’s polar regions and high-altitude plateaus, the reality is often far more complex and dramatically sculpted. Here, the wind is a relentless artist, and its medium is the snow itself. The result is a breathtaking and treacherous phenomenon known as sastrugi.

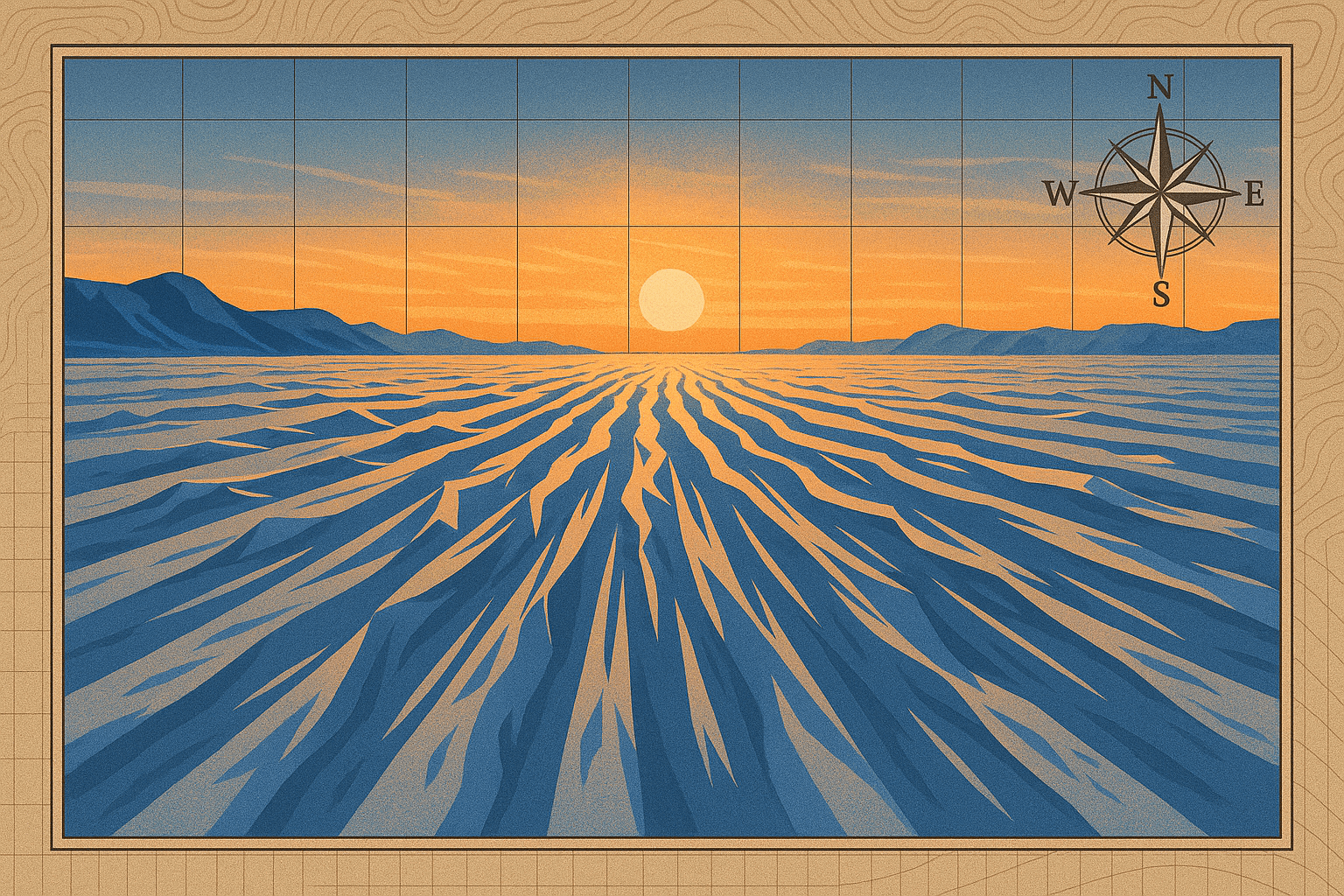

Derived from a Russian word (singular: sastruga), sastrugi are irregular, sharp, and often parallel ridges of hard-packed snow, carved by the ceaseless action of the wind. They can range from a few centimeters high, creating a washboard-like surface, to formidable barriers over a meter tall. To the uninitiated, they might look like frozen waves on a stark white sea or the fossilized spine of some immense, buried creature. For those who must travel across them, they are a defining feature of the polar world—a feature that can be both a guide and a grave danger.

The Anatomy of a Wind-Carved World

Sastrugi are not formed by gentle breezes. Their creation requires a specific and powerful recipe of geographic and atmospheric conditions. The key ingredients are:

- Persistent, Strong Wind: A steady, directional wind blowing consistently over long periods is the primary force. The powerful katabatic winds that pour down from the high plateaus of Antarctica and Greenland are perfect for sculpting vast fields of sastrugi.

- Cold, Dry Snow: The snow must be cold and unconsolidated enough for individual crystals to be lifted and transported by the wind. Wet, heavy snow doesn’t form sharp sastrugi.

- Time and an Open Expanse: The process needs time to develop and a large, open area, like an ice sheet or frozen lake, where the wind can act without obstruction.

The formation process is a dynamic interplay of erosion and deposition. The wind acts like a sandblaster, a process known as saltation, where it picks up loose snow crystals and hurls them against the surface. Softer snow is scoured away, while harder, more compacted snow is left behind. The wind erodes the upwind (windward) side of any small irregularity, creating a steep, often undercut face. The transported snow is then deposited on the downwind (leeward) side, forming a longer, gentler slope.

Over time, this process repeats and magnifies, creating a field of parallel ridges all perfectly aligned with the prevailing wind direction. The resulting landscape is a physical record of the atmosphere’s power, a frozen, three-dimensional weather map.

Navigating a Frozen Labyrinth: The Human Geography of Sastrugi

For centuries, sastrugi have been a critical element of human geography in the polar regions. They profoundly impact how people move, navigate, and survive in these extreme environments.

The Treacherous Obstacle

Crossing a field of large sastrugi is an exhausting and perilous task. For polar explorers on skis, pulling heavy sleds (or pulks), it’s a nightmare. The uneven, rock-hard ridges can catch ski edges, leading to falls and twisted ankles. Sleds must be hauled up and over each ridge, and their runners are prone to cracking or breaking on the unforgiving surfaces.

Legendary polar explorer Børge Ousland described crossing a particularly bad field of sastrugi in Antarctica as “like pulling a sledge through a ruin of a town.” Travel speed plummets, and energy expenditure skyrockets. In whiteout conditions, when the sky and snow blend into a single, featureless void, sastrugi become invisible traps. A traveler can easily walk off a meter-high, sharp-edged ridge, resulting in serious injury far from any hope of rescue.

The Unfailing Compass

Despite the danger, sastrugi offer one invaluable gift: direction. Because they are aligned with the prevailing wind, they serve as a near-perfect natural compass. The steep, eroded face always points directly into the wind. Early 20th-century explorers like Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott relied heavily on reading the sastrugi to maintain their course during their race to the South Pole, especially when magnetic compasses became unreliable near the poles or when the sun was obscured.

Even today, with modern GPS technology, polar travelers use sastrugi as a quick, reliable reference. A glance at the snow tells them the direction of the dominant wind, helping them orient themselves and anticipate weather changes. Traveling parallel to the ridges is relatively easy, while traveling perpendicular to them is a grueling battle.

A Climate Story Written in Snow

Beyond their impact on human travel, sastrugi are a valuable tool for scientists trying to understand our planet’s climate. As physical geography, they are a direct expression of local atmospheric conditions. Glaciologists and climatologists study vast sastrugi fields to decipher patterns of wind flow over the massive ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland.

By analyzing satellite imagery, such as data from NASA’s ICESat (Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite), scientists can map the orientation, size, and spacing of sastrugi over thousands of square kilometers. This data reveals crucial information about the behavior of powerful katabatic winds, which are a major driver of atmospheric circulation in the polar regions. Understanding these wind patterns is essential for refining global climate models and predicting how ice sheets might respond to a warming world.

The size of the sastrugi can indicate wind speed, while their shape can provide clues about the properties of the snow. In essence, these frozen ridges are a climatic record, a story of wind and weather etched onto the landscape itself.

Where to Find These Wind-Swept Wonders

Sastrugi are synonymous with the planet’s coldest, windiest places. The Antarctic Plateau is the undisputed king of sastrugi, where relentless winds have sculpted the ice sheet into a continent-sized art installation. The interior of Greenland is another prime location. But they are not limited to the poles. You can find them in any environment with the right conditions:

- High-altitude mountain ranges like the Himalayas and the Andes.

- Vast, windswept plains in Siberia and northern Canada.

- Large frozen bodies of water, such as Lake Baikal in Russia, can develop sastrugi on their snowy surfaces during winter.

So, the next time you see a photograph of a polar expedition or a documentary about Antarctica, look closely at the ground. Those are not just random bumps in the snow. They are sastrugi—a beautiful, dangerous, and deeply informative geographical phenomenon, the wind’s unforgettable signature on the world’s coldest canvases.