There is a raw, untamed poetry to a coastline carved by the relentless power of the sea. Where land meets water, a dramatic and ever-changing landscape is born, full of towering columns, treacherous reefs, and isolated islets. To describe this world, we can’t just rely on simple terms like “rock” or “island.” Instead, we can turn to a rich and specific vocabulary, much of it inherited from the Old Norse language of the Vikings who expertly navigated these very shores.

This is the language of physical geography at its most evocative. Let’s journey to the wild coasts of Scotland, Norway, and Iceland to explore the meaning behind skerries, holms, and sea stacks, and understand the stories they tell.

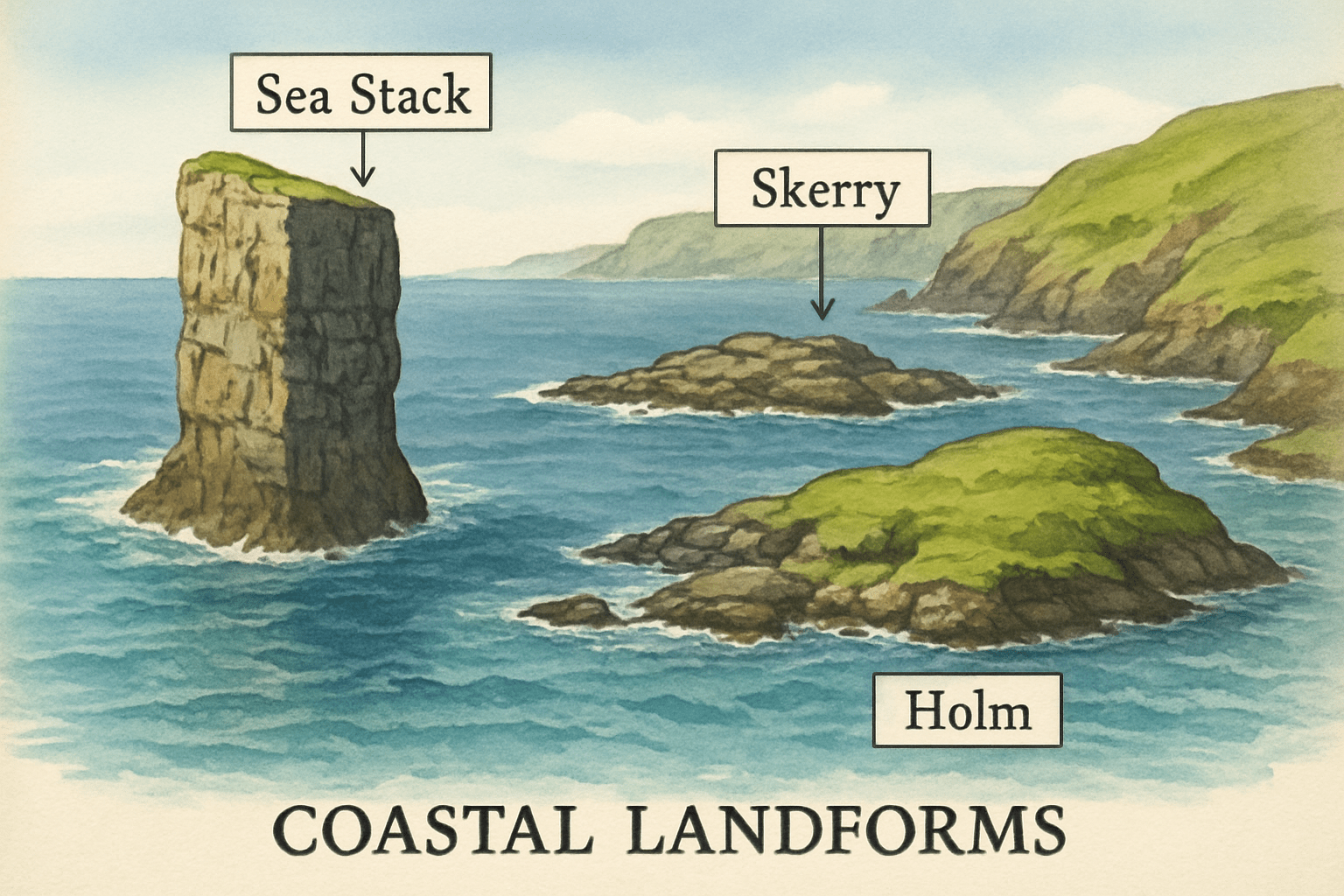

The Sea Stack: A Lone Sentinel of a Lost Coastline

Perhaps the most iconic of all coastal features is the sea stack. This is a steep, vertical, and often column-shaped pillar of rock standing in the sea near a coastline, completely detached from the mainland. They are ghosts of a former landscape, powerful reminders that the land you stand on is not permanent.

The creation of a sea stack is a slow, violent epic told over millennia. It begins with a headland jutting out into the sea. The waves, armed with sand and shingle, are tireless sculptors.

- They attack weaknesses and cracks in the headland, hollowing them out to form sea caves.

- Sometimes, caves on opposite sides of the headland meet, or a single cave erodes straight through, creating a spectacular sea arch.

- Finally, the lintel of the arch, battered by wind and water, succumbs to gravity and collapses. All that remains is the steadfast seaward pillar: the sea stack.

Examples of these majestic features are legendary:

- The Old Man of Hoy, Scotland: Rising 137 meters (449 ft) from the Atlantic off the Orkney island of Hoy, this red sandstone stack is one of the most famous in the world. It’s a relatively young feature in geological terms, likely less than 400 years old, and a celebrated challenge for rock climbers.

- Reynisdrangar, Iceland: Off the black sand beach of Reynisfjara near Vík stand the jagged basalt stacks of Reynisdrangar. Local folklore provides a more romantic origin story: the stacks are two trolls who were turned to stone by the rising sun when they were caught trying to drag a three-masted ship to shore.

The Skerry: A Hidden Danger, a Haven for Wildlife

Move from the dramatic height of the stack to the low-lying menace of the skerry. The word comes from the Old Norse sker, meaning “a rock in the sea”, and its DNA is found all over the coastlines of Northern Europe.

A skerry is a rock or a small, rocky islet that is too small for human habitation. Crucially, many skerries are submerged during high tide, making them a significant navigational hazard. While a stack is defined by its height and isolation, a skerry is defined by its low profile and its treacherous nature.

These features are rarely singular; they often appear in vast, scattered groups known as a “skerries” or, in Norway, a skjærgård.

- The Norwegian Skjærgård: Along much of the Norwegian coast, a vast archipelago of thousands of skerries runs parallel to the mainland. This “skerry-guard” creates a sheltered channel of calm water, protecting coastal shipping from the fury of the North Sea and the Atlantic. It is a defining feature of the country’s geography.

- Skerryvore, Scotland: The name of this remote reef 19 km southwest of Tiree in the Inner Hebrides translates to “the great skerry.” Its danger to shipping was so great that it became the site of one of the world’s most elegant and challenging lighthouse constructions in the 1840s, a testament to the human need to tame the peril of the skerry.

Though dangerous to sailors, skerries are vital havens for wildlife, providing undisturbed breeding grounds for seabirds and haul-out spots for seals.

The Holm: An Islet Between Rock and Island

Our final term, the holm, occupies the space between a barren skerry and a full-fledged island. From the Old Norse holmr, this word describes a small, rounded islet. Unlike a skerry, a holm is consistently above water and is typically covered in soil and vegetation. It’s a piece of land you could stand on, have a picnic on, or even graze a few sheep on, but it’s generally too small for permanent settlement.

The term is embedded in place names across the Norse world. Stockholm, the capital of Sweden, is named for the islets on which it was founded. In the UK, you’ll find it in places like Holm, Orkney or Steep Holm in the Bristol Channel.

The key difference is habitability and size. If a skerry is a hazardous rock, and an island is a place you could live, a holm is the green, welcoming stepping-stone in between.

- Lamb Holm, Scotland: This small, uninhabited holm in Orkney is famous for a remarkable piece of human geography: the ornate Italian Chapel. It was built by Italian prisoners of war during WWII who were stationed there to help construct the Churchill Barriers (which connect Lamb Holm to other islands).

- Grassholm, Wales: This holm off the Pembrokeshire coast is a fantastic example of its role in nature. While uninhabited by humans, it is home to a massive gannet colony—around 39,000 pairs—making it a globally important seabird sanctuary.

The Language of the Shoreline

Understanding this vocabulary does more than just help us label rocks; it connects us to the history of the people who lived and sailed among these features. For them, the difference between a holm (a potential shelter) and a skerry (a potential disaster) was a matter of life and death.

Here’s a simple cheat sheet to remember the key differences:

- Sea Stack: A tall, vertical pillar of rock. The last remnant of a collapsed sea arch.

- Sea Arch: A natural bridge of rock extending from a coastline. The stage before a stack.

- Skerry: A low-lying, barren rock or reef. Often submerged at high tide and a danger to ships.

- Holm: A small, vegetated islet. Bigger than a skerry, smaller than an island.

The next time you stand on a windswept cliff, listen to the waves crashing below. You’re not just looking at a pretty view; you’re witnessing the slow, powerful creation of stacks, arches, and skerries. You’re seeing a landscape that has its own ancient, precise, and poetic language—a language that gives voice to the endless conversation between land and sea.