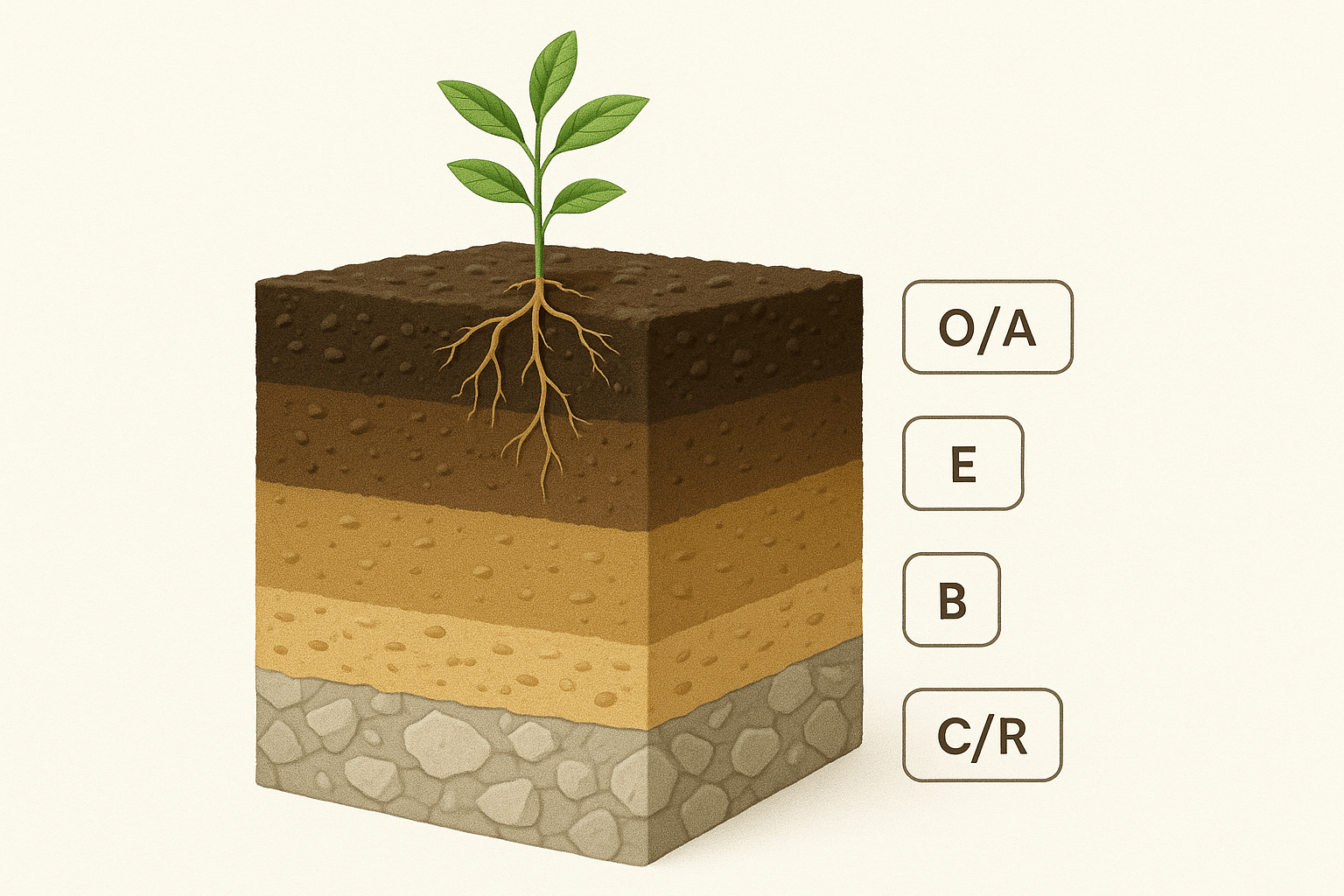

A vertical slice through these layers is called a soil profile. Far from being a random jumble, each horizon in the profile is the result of specific processes. Think of it as a natural factory where inputs like rainwater, fallen leaves, and microscopic organisms work on a raw material—the underlying rock—to manufacture the vibrant, life-sustaining medium we call soil. Let’s dig in and explore the master horizons that tell this incredible story from the top down.

The Master Horizons: Decoding the Earth’s Biography

Scientists use a simple lettering system to label the main layers. While there are many subdivisions, understanding the four master horizons—O, A, B, and C—is the key to unlocking the secrets of the soil.

The O Horizon: The Organic Frontier

The very top layer in many undisturbed soils, especially in forests, is the O Horizon. The “O” stands for organic. This layer is composed almost entirely of organic matter in various stages of decomposition: freshly fallen leaves, pine needles, twigs, mosses, and the remains of insects and other small animals.

What it tells us: The thickness and character of the O horizon are a direct reflection of the local biology and climate. A thick, spongy O horizon points to a productive forest ecosystem where organic matter accumulates faster than it can decompose. In a cold, wet climate like that of a boreal forest, decomposition is slow, leading to a deep, acidic layer of peat-like material. Conversely, in a hot, humid tropical rainforest, decomposition is so rapid that the O horizon is often surprisingly thin, as nutrients are almost immediately recycled by the riot of life.

The A Horizon: Topsoil and the Zone of Life

Just beneath the O horizon lies the A Horizon, more commonly known as topsoil. This is a crucial layer where mineral particles are intimately mixed with dark, fully decomposed organic matter called humus. This humus is what gives topsoil its characteristic dark color and crumbly structure.

The A horizon is the primary zone of biological activity. It’s teeming with earthworms, insects, fungi, and trillions of bacteria that are essential for nutrient cycling. Water percolating through this layer begins a process called eluviation—the washing out and carrying away of fine particles like clay and soluble minerals deeper into the soil.

What it tells us: The A horizon is the engine room of terrestrial ecosystems and agriculture. A thick, dark, and nutrient-rich A horizon is a sign of a highly fertile soil. The world’s great breadbaskets, from the American Great Plains to the Ukrainian steppes, are built upon soils (Mollisols and Chernozems) with exceptionally deep A horizons developed under native grasslands over thousands of years. Its health tells a story of ecological stability or, in some cases, human impact like erosion from poor farming practices.

The B Horizon: The Subsoil and Zone of Accumulation

As water carries materials down from the A horizon, it deposits them in the layer below: the B Horizon, or subsoil. This process of deposition is called illuviation. Because it’s a zone of accumulation, the B horizon is often denser and has a higher clay content than the topsoil. It typically has less organic matter, making it lighter in color.

However, “lighter” doesn’t mean less interesting. The B horizon can be a vibrant canvas. The accumulation of iron and aluminum oxides can stain the soil brilliant reds and yellows, a common feature in older, highly weathered soils of humid regions. In arid and semi-arid climates, the B horizon tells a different story. Evaporation may draw water upward, leaving behind concentrated bands of white calcium carbonate (caliche), a clear indicator of a dry climate.

What it tells us: The B horizon is a powerful climate indicator. Its structure, color, and chemistry reveal the history of water movement through the soil. A well-developed, clay-rich B horizon suggests a landscape that has been stable for a very long time, allowing these slow processes to create a distinct layer. It’s the soil’s long-term memory.

The C Horizon: The Parent Material

Below the dynamic zones of life and accumulation lies the C Horizon. This layer consists of large, weathered chunks of rock and unconsolidated material. It is the parent material from which the A and B horizons ultimately developed. It lacks the structure and organic matter of the upper layers and more closely resembles the geology beneath it. It’s essentially the raw material for the soil factory, only lightly touched by the soil-forming processes occurring above.

What it tells us: The C horizon is the direct link to the site’s geology. Is the soil forming from weathered granite, limestone, sandstone, or perhaps from material transported by glaciers (glacial till) or rivers (alluvium)? The chemistry of this parent material sets the initial conditions for the entire soil profile, influencing everything from its pH to its mineral nutrient content for millennia to come.

Below the C horizon, one might find the R Horizon—solid, unweathered bedrock.

Reading the Full Story

A soil scientist doesn’t just identify the layers; they read the relationships between them to understand the geography of a place. The story is in the transitions, the thicknesses, and the contrasts.

- A desert soil (Aridisol) might have a thin A horizon, or none at all, sitting directly on a B horizon cemented with calcium carbonate, telling a clear story of aridity, sparse vegetation, and minimal water percolation.

- A coniferous forest soil (Spodosol) in a cool, rainy region will show a stark profile: a thick, acidic O horizon of pine needles, a bleached-white, heavily eluviated A horizon, and a dramatic B horizon stained dark red and black with illuviated iron and humus. This paints a picture of acidic water stripping the topsoil and depositing its contents below.

By understanding this vertical geography, we can map soil types across continents, make informed decisions about agriculture and land management, and even interpret past environmental conditions. The ground beneath our feet is not inert. It is a dynamic, living archive, a biography of the landscape. The next time you see a cross-section of earth, take a closer look. You might just be able to read the first few chapters of its incredible story.