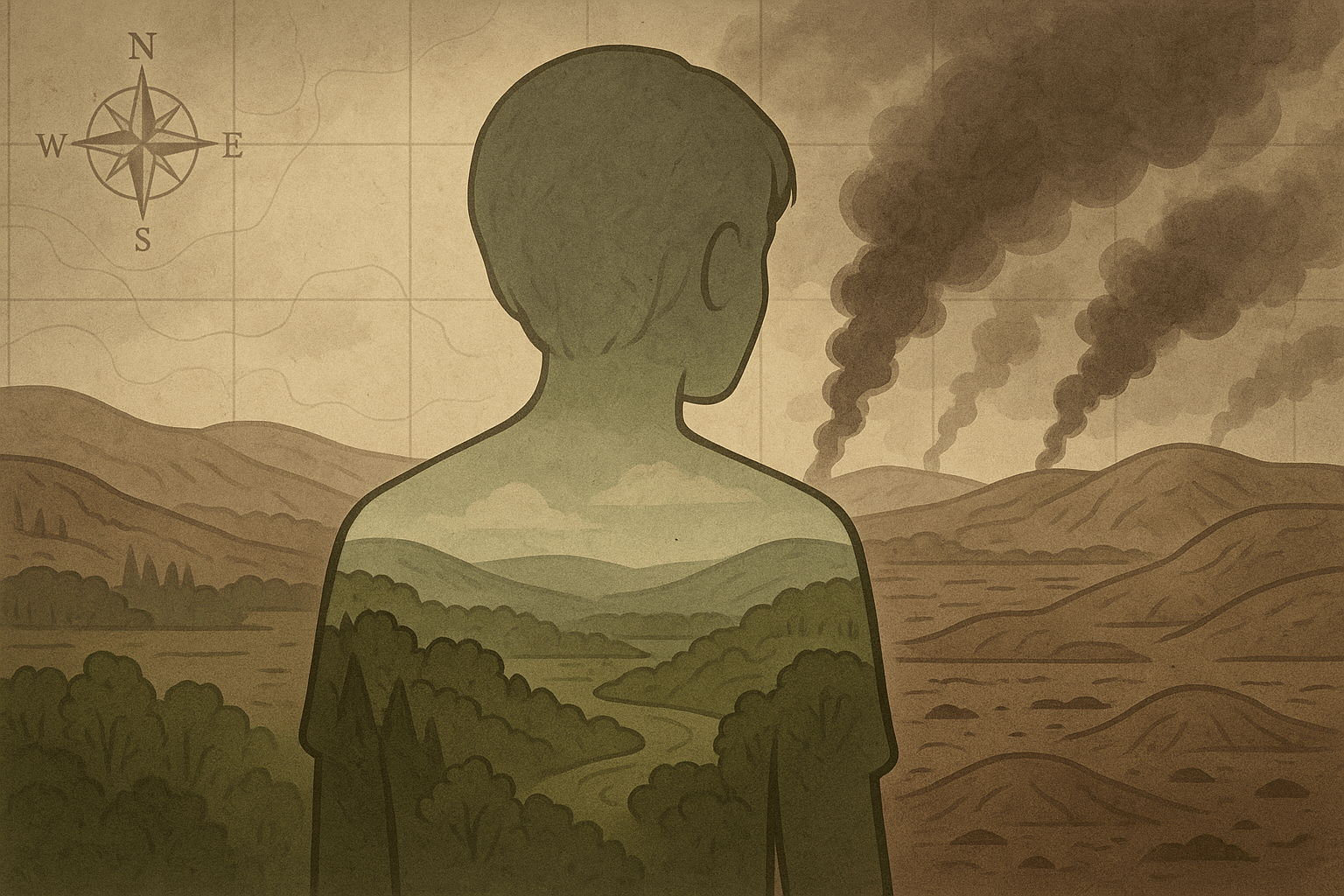

There’s a specific feeling many of us know intimately, even if we can’t name it. It’s the quiet ache of returning to a childhood forest to find it has become a subdivision. It’s the pang of seeing a once-vibrant coral reef bleached bone-white. It’s the unease of a summer that feels unnaturally hot and smoky. This feeling is not nostalgia—the wistful longing for a past you’ve left behind. This is a grief for a place that has left you, even though you haven’t moved an inch. This feeling has a name: solastalgia.

Coined by Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht, the term elegantly captures a distinctly modern form of psychic pain. It combines the Latin word sōlācium (comfort, solace) and the Greek root -algia (pain, suffering). Solastalgia is, quite literally, the pain of losing solace in your home environment. It is the distress caused by the negative transformation of a cherished landscape, a form of homesickness you experience while you are still at home.

The Geography of Grief

Solastalgia is deeply geographical. Our identities are interwoven with the landscapes we inhabit. The curve of a river, the silhouette of a mountain range against the sunset, the scent of pine after rain—these are not just backdrops to our lives; they are part of our story. When these geographical anchors are degraded or destroyed, our own sense of well-being and identity can erode with them. This is not a hypothetical phenomenon; it’s a lived reality for communities across the globe.

Case Study: The Charred Hills of California, USA

For decades, the golden, oak-studded hills of California have been a cornerstone of the state’s identity. But as climate change fuels hotter, drier conditions, the annual fire season has transformed into a year-round threat of unprecedented scale and ferocity. For residents of towns like Paradise, decimated by the 2018 Camp Fire, or communities in Sonoma and Napa counties, the landscape is now etched with trauma.

The solastalgia here is multi-sensory. The familiar sight of rolling green or golden hills is replaced by a monochrome vista of black, skeletal trees. The air, once clear, is frequently thick with a smoky haze that stings the eyes and lungs. A beloved hiking trail is now a path through ash and debris. For these residents, looking out the window is no longer a source of comfort but a constant, painful reminder of loss, fear, and the precarity of their home. The landscape itself feels alien and hostile.

Case Study: The Vanishing Glaciers of the Alps, Europe

In the high-altitude valleys of the European Alps, communities have lived for centuries in the shadow of majestic glaciers. These rivers of ice are more than just geographical features; they are woven into the cultural fabric, the local economy, and the spiritual identity of the region. They are landmarks, tourist draws, and vital sources of fresh water. But they are disappearing at an alarming rate.

In places like Austria and Switzerland, the retreat of glaciers like the Pasterze or the Aletsch is a slow-motion catastrophe. Tour guides who once led visitors across vast expanses of ice now point to where it used to be. The visual change is stark, as brilliant white is replaced by grim, grey rock. This loss has prompted public “funerals” for glaciers, a poignant expression of collective grief. For the people of the Alps, this is not an abstract environmental issue. It’s the death of a silent, ancient neighbor, creating a profound sense of solastalgia for a landscape that is visibly shrinking and dying before their eyes.

Case Study: The Advancing Sands of the Sahel, Africa

Stretching across the width of Africa, the Sahel is a semi-arid transitional zone between the Sahara Desert to the north and the savannas to the south. For millennia, pastoralist and farming communities have built their lives around its delicate ecological balance. Now, due to a combination of climate change-induced drought and unsustainable land-use practices, the desert is expanding southward in a process known as desertification.

For a Fulani herder or a Malian farmer, this is an existential crisis. The land that sustained their ancestors is turning to dust. Wells are running dry, grazing lands are vanishing, and the predictable rhythms of the seasons have been broken. This loss goes far beyond economics. It unravels a way of life, erasing cultural knowledge and severing a deep, ancestral connection to the land. The solastalgia experienced here is a chronic distress born from watching the very source of life and identity become barren and uninhabitable.

From Landscape to Mindscape

Solastalgia bridges the gap between physical and human geography, demonstrating that the health of our planet and the health of our minds are inextricably linked. It is recognized as a contributing factor to serious mental health challenges, including:

- Anxiety and Depression: The constant stress and grief associated with a degrading environment can trigger or worsen clinical anxiety and depression.

- Sense of Powerlessness: Watching immense environmental forces transform your home can lead to feelings of hopelessness and a loss of agency.

- Loss of Identity: When a “place identity” is a core part of who you are, its destruction can feel like a personal attack, leading to an identity crisis.

Charting a Path from Grief to Action

Recognizing and naming solastalgia is a critical first step. It validates the legitimacy of the emotional pain people feel in the face of environmental change. It reframes ecological crises not as distant problems for scientists and politicians, but as immediate, personal, and emotional threats to our well-being.

While the feeling is one of loss, it doesn’t have to end in despair. This deep, place-based grief can also be a powerful motivator. The pain of solastalgia underscores what’s at stake. It reminds us that protecting ecosystems is not just about preserving biodiversity or stabilizing the climate; it’s about defending our homes, our cultures, our memories, and our sanity. By understanding the geography of our grief, we can better chart a map toward collective action, fighting to heal the places that give us solace and make us who we are.