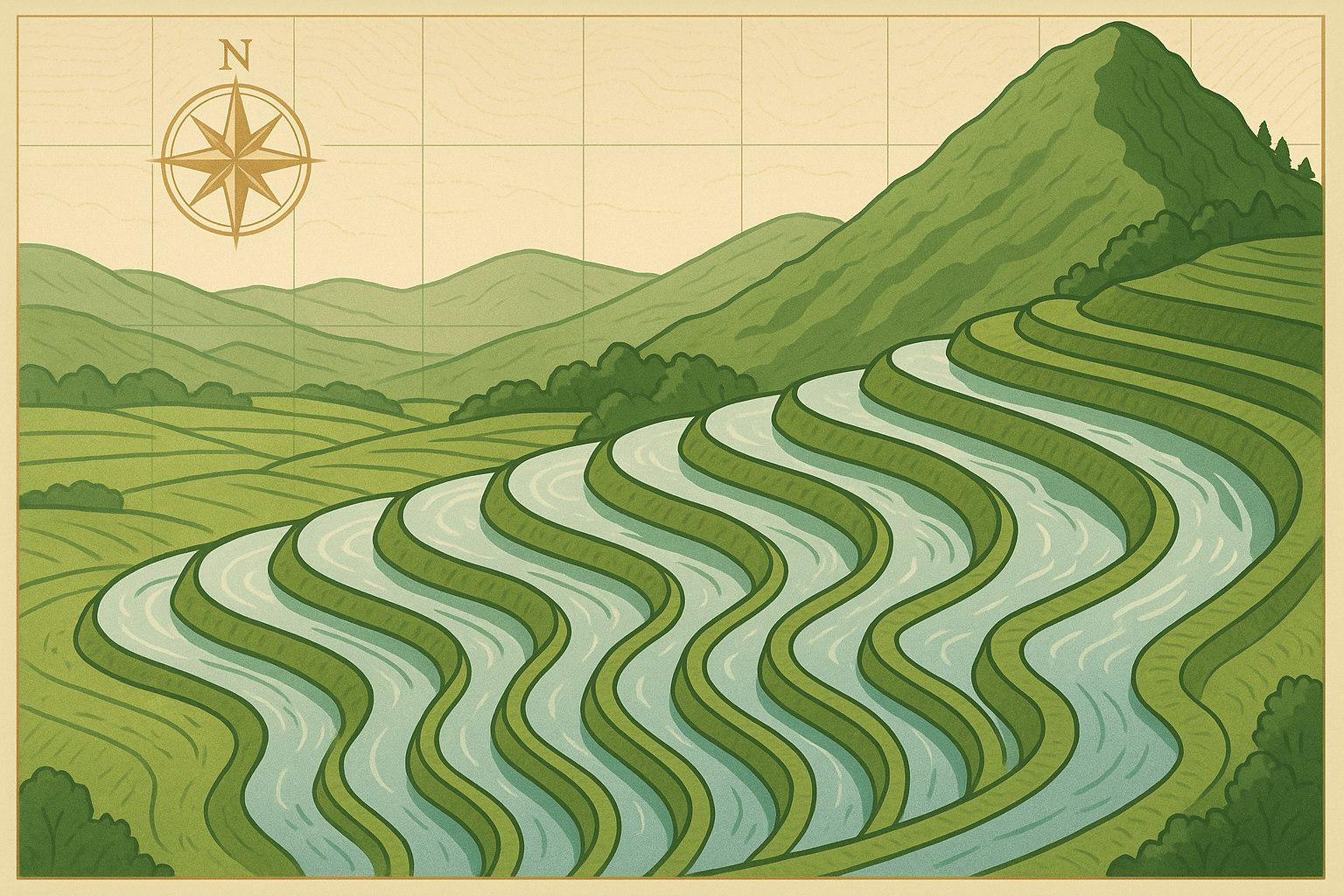

Picture a staircase built for giants, ascending not to a castle in the clouds, but into the very heart of a mountain. Its steps are not cold stone, but vibrant, living earth, brimming with crops. This is the breathtaking reality of terraced farming, an ancient and ingenious method of agriculture that represents one of the most remarkable intersections of human geography and the physical world.

For millennia, communities living in mountainous regions have faced a fundamental geographical challenge: how do you grow food on a steep, unforgiving slope? Their answer was to reshape the land itself, carving impossible inclines into productive, sustainable farmland. These terraces are more than just farms; they are living monuments to human resilience, ecological wisdom, and a deep, symbiotic relationship with the earth.

The Geographical Problem and the Elegant Solution

Farming on a steep hillside is a battle against gravity and hydrology. When rain falls, it cascades downwards, gaining speed and energy. This has several devastating effects:

- Soil Erosion: The rushing water washes away nutrient-rich topsoil, leaving behind barren, rocky ground.

- Water Loss: Water runs off the surface so quickly that it has no time to soak into the ground to nourish plant roots.

- Landslides: Saturated, unstable slopes can easily give way, posing a danger to everything below.

Terracing is the elegant solution to all these problems. By cutting a series of level, step-like platforms into a hillside, farmers fundamentally alter the local geography. Each terrace is a flat plain, often supported by a retaining wall made of stone or packed earth. When rain falls, it lands on a level surface. Its flow is arrested, allowing the water to slowly percolate into the soil, providing deep and consistent hydration for crops. The retaining walls stabilize the slope, and the drastic reduction in water runoff all but eliminates soil erosion. In essence, humans created a system that works with gravity and water, not against them.

The Andean Marvels: The Inca and Their Andenes

Perhaps no civilization mastered terracing on a grander scale than the Inca in the Andes Mountains of South America. The vast, rugged spine of the Andes presents some of the world’s most challenging agricultural terrain. Yet, the Inca Empire managed to feed millions, thanks in large part to their sophisticated terrace systems, known as andenes in the local Quechua language.

Sites like Machu Picchu and the Sacred Valley of Peru, particularly around Pisac and Ollantaytambo, showcase the sheer genius of Inca engineering. These were not simply flattened strips of dirt. The Inca constructed their andenes with a complex, layered internal structure designed for optimal drainage and soil health: a base layer of coarse gravel, a middle layer of sand, and a top layer of rich soil, often carried up from the valleys below.

Even more remarkably, the Inca manipulated local geographical phenomena to their advantage. The stone retaining walls of the terraces would absorb solar radiation during the day and slowly release that heat at night. This created a unique microclimate on each step, protecting sensitive crops like maize from the deadly high-altitude frost. This allowed them to grow a stunning variety of foods, from thousands of potato cultivars to quinoa and corn, at elevations once considered inhospitable for agriculture.

Stairways to Heaven: The Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras

Half a world away, in the mountainous Cordillera region of the northern Philippines, another culture perfected the art of terracing. The Ifugao people, over a period of 2,000 years, hand-carved what are often called the “Eighth Wonder of the World”: the Banaue Rice Terraces. Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, these terraces are a testament to community effort and ecological harmony.

Unlike the Inca’s stone-walled structures, the Ifugao terraces are primarily carved from the earth and mud, following the natural contours of the mountains like a flowing green map. Their genius lies in their intricate irrigation system. Water is captured from mountain-top forests and springs—which are carefully preserved as part of the ecosystem—and channeled downwards through an elaborate network of bamboo pipes, sluices, and canals. The system is gravity-fed, with each terrace receiving water before letting the excess flow to the one below.

This is a living cultural landscape. The Ifugao community’s entire way of life, from social rituals to daily calendars, revolves around the planting and harvesting cycles of the rice grown on these “stairways to heaven.” The *subak* system in Bali, Indonesia, is another famed example of a socially and spiritually integrated irrigation system for terraced rice paddies, also recognized by UNESCO.

A Global Practice Forged by Geography

While the Andes and the Philippines host some of the most famous examples, terracing is a global phenomenon, an adaptive strategy that arose independently in mountainous regions across the planet.

- In China, the Longji (Dragon’s Backbone) Rice Terraces in Guangxi province ripple across the hillsides like a dragon’s scales, creating patterns that change with the seasons.

- In Europe, ancient terraces are vital for viticulture. The steep slopes of the Douro Valley in Portugal and the iconic coastal cliffs of Cinque Terre in Italy are covered in terraced vineyards that have produced wine and olives for centuries.

- In the Himalayas of Nepal and India, terraces are essential for growing millet, barley, and vegetables, forming the backbone of subsistence farming.

Each example shows how diverse cultures, faced with the same physical constraint of steep terrain, developed a similar, brilliant solution.

An Enduring Legacy in a Modern World

Today, these ancient landscapes offer profound lessons in sustainability. In an era of industrial agriculture that often contributes to soil degradation and water depletion, terraced farming stands as a model of conservation. It conserves water, preserves precious topsoil, increases biodiversity, and enhances a landscape’s resilience to climate change by better managing heavy rainfall.

However, these systems face modern threats. The intense labor required to maintain them is a challenge as younger generations migrate to cities for other opportunities. Tourism, while providing income, can also place a strain on these fragile ecosystems if not managed properly.

Nonetheless, terraced farms are far more than just a relic of the past. They are powerful, beautiful reminders that human beings can live not just on the earth, but in partnership with it. They show us that by understanding the forces of geography—slope, water, soil, and sun—we can sculpt the world not through domination, but with ingenuity and respect, creating landscapes that are both productive and profoundly beautiful.