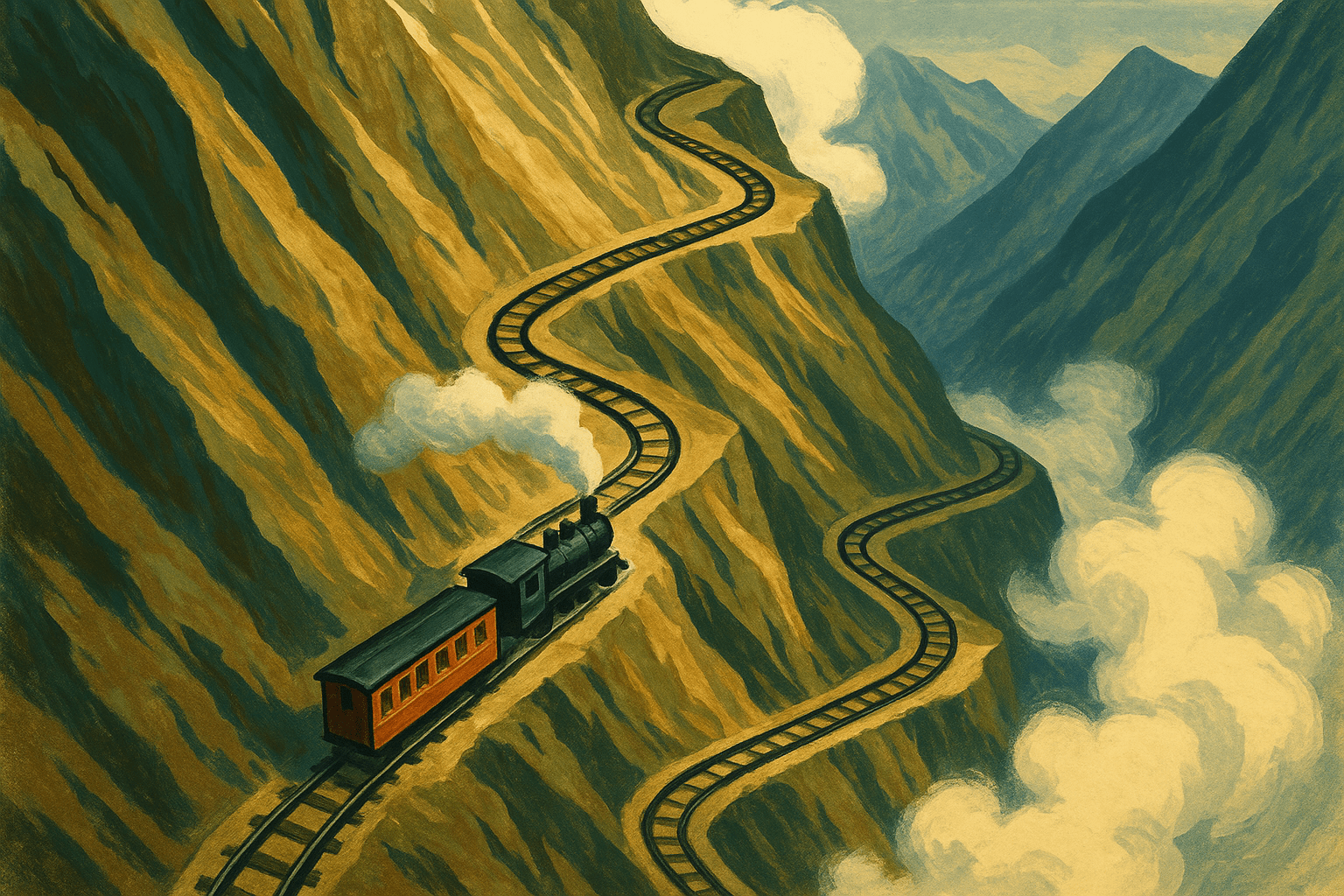

Imagine a train that doesn’t just cross landscapes, but defies them. A steel serpent that doesn’t skirt the mountains, but climbs them, scaling sheer rock faces and breathing the thin air of the heavens. This isn’t a fantasy; it’s the Ferrocarril Central Andino, or the Andean Central Railway, a ribbon of track that represents one of humanity’s most audacious and dramatic battles with physical geography.

An Impassable Wall of Stone

To understand the railway, one must first understand the geography of Peru. The country is split into three distinct longitudinal zones: the arid coast (costa), the formidable Andes mountains (sierra), and the Amazon rainforest (selva). For centuries, the Andes stood as a colossal, near-impenetrable barrier. The capital, Lima, situated on the coast, was economically and culturally isolated from the vast mineral and agricultural wealth locked away in the high sierra.

In the mid-19th century, the demand for this wealth—silver, copper, and lead—created a powerful economic incentive. The question was not *why* to cross the Andes, but *how*. The answer came in the form of an audacious American entrepreneur named Henry Meiggs, who in 1868 boldly promised the Peruvian government he could build a railway from the port of Callao, through Lima, and up into the mineral heartland. Many called him a madman. The route required ascending from sea level to over 15,000 feet in just over 100 miles, a gradient that seemed utterly impossible for a conventional train.

Engineering Against the Elements

The construction of the Ferrocarril Central Andino is a masterclass in overcoming geographical constraints through sheer ingenuity. The engineers, faced with cliffs too steep for gentle curves, devised a toolkit of breathtaking solutions that make the journey a spectacle to this day.

The Devil’s Backwards: Conquering Gradient with Zig-Zags

The most iconic feature of the railway is its extensive use of switchbacks, or zig-zags. When the slope became too steep for the locomotive to climb directly, the engineers didn’t give up; they went sideways. The train pulls onto a short stub of track, a switch is flipped behind it, and the engine then pushes the train in reverse up the next section of the incline. The line has 22 of these switchbacks, which locals dramatically dubbed “El Balcon del Diablo” (The Devil’s Balcony) or “The Devil’s Backwards.” This simple but brilliant solution allowed the railway to gain altitude rapidly without carving impossible, looping tunnels into the mountainside.

Bridges to the Sky

Where the mountainside crumbled away into a gorge, the railway had to leap across it. The line boasts 59 bridges, many of which are terrifying and spectacular in equal measure. The most famous is the Infiernillo Bridge (Little Hell Bridge). The name says it all. The railway emerges from a tunnel, crosses the slender steel bridge over a dizzying chasm, and immediately enters another tunnel on the other side of the canyon. From below, the bridge appears impossibly suspended between two black holes in the rock.

Another marvel is the Carrión Bridge, which, upon its completion, was one of the highest railway viaducts in the world, spanning a deep valley on towering steel piers that seem to vanish into the mist below.

Burrowing Through the Peaks

If the railway couldn’t go up or around, it went through. The line is punctuated by 66 tunnels, blasted through solid Andean rock by workers battling not only the stone but also the debilitating effects of altitude sickness (soroche). The crowning achievement is the Galera Tunnel. At 4,781 meters (15,686 feet), it was the highest standard-gauge railway tunnel in the world for over a century. Passing through it, passengers are officially crossing the continental divide, with waters on one side flowing to the Pacific and on the other, to the Atlantic via the Amazon River.

The Railway that Forged a New Geography

The Ferrocarril Central Andino was far more than an engineering project; it was an instrument of geographical transformation. Its completion fundamentally rewired the economic and human geography of Peru.

- The Mineral Artery: The railway’s primary purpose was realized almost immediately. It became the essential artery for the mining industry. Cities like La Oroya, a major smelting center, and Cerro de Pasco boomed, becoming hubs of industry deep within the Andes. The railway was the lifeline that carried millions of tons of copper, lead, and zinc down to the Port of Callao for export, fueling the Peruvian economy.

- Connecting a Divided Nation: For the first time, there was a reliable connection between the capital and the central sierra. This facilitated not just the movement of goods, but of people and ideas. The railway helped integrate the indigenous populations of the highlands more closely with the coastal centers of power.

- The Agricultural Link: The line doesn’t just end in the mining towns. It extends to Huancayo, the vibrant commercial center of the fertile Mantaro Valley. The railway allowed agricultural products from this breadbasket region—potatoes, grains, and livestock—to be transported efficiently to the massive market of Lima.

Riding the Rails in the Clouds Today

While the passenger service has become more sporadic over the years, focusing on tourist-oriented trips, the Ferrocarril Central Andino remains a workhorse. It continues to be one of the world’s most important mineral railways, with freight trains hauling the riches of the Andes down to the coast every day.

For those lucky enough to board the passenger train, the journey is an unforgettable geographical expedition. It begins in the grey coastal desert around Lima, climbs through the greening valleys of the lower Andes, and punches through the clouds into the stark, beautiful, high-altitude grasslands of the puna. Onboard, nurses are ready with oxygen tanks for those struggling with the altitude, a stark reminder that you are traveling in a realm where humans—and their machines—were never meant to be.

The Andean Central Railway is more than tracks and steel. It is a scar of ambition carved into the face of the planet, a testament to the human will to reshape geography, and a living, breathing monument to the engineers who dared to lay rails in the clouds.