The Geographic Anomaly: A Desert Beside an Ocean

To understand how you can pull water from the air in a place defined by its lack of water, we must first look at the unique physical geography of the region. The Atacama’s extreme aridity is the result of a powerful “double rain shadow.”

- The Andes Barrier: To the east, the towering Andes mountains create a formidable wall, blocking any moisture-laden winds from the Amazon Basin.

- The Coastal Barrier: To the west, a high-pressure system known as the Pacific Anticyclone pushes winds away from the continent, preventing the formation of large rain systems over the ocean.

Adding to this effect is the cold, northward-flowing Humboldt Current in the Pacific Ocean. This chilly ocean current cools the air above it, creating a thermal inversion—a layer of cool, dense air trapped beneath a warmer, lighter layer. This inversion acts like a lid, preventing the cool air from rising and forming rain clouds. The very geographical forces that make the Atacama a desert are, paradoxically, the same ones that create its most precious resource: fog.

The Camanchaca: A River in the Sky

While rain is virtually non-existent, the Atacama is frequently blanketed by a thick, wet fog known locally as the Camanchaca. The name comes from the Aymara language and means “darkness.” When it rolls in, visibility can drop to just a few meters. This isn’t just any fog; it’s a specific type called advection fog, born from the interaction between ocean and land.

Here’s how it forms: Warmer, moist air from the vast Pacific Ocean blows eastward toward the South American continent. As this air passes over the frigid Humboldt Current, it is rapidly cooled to its dew point. At this temperature, the invisible water vapor in the air condenses into microscopic liquid water droplets, forming a dense, low-lying cloud. This massive bank of fog is then pushed inland by prevailing winds until it collides with the coastal mountain range, the Cordillera de la Costa. The fog is too low and dense to pass over the mountains, so it clings to their western slopes, bathing the arid hillsides in moisture.

This “river in the sky” carries a surprising amount of water. While the droplets are too small to fall as rain (each one is between 1 and 40 microns in diameter), the fog itself can contain up to 0.5 grams of water per cubic meter.

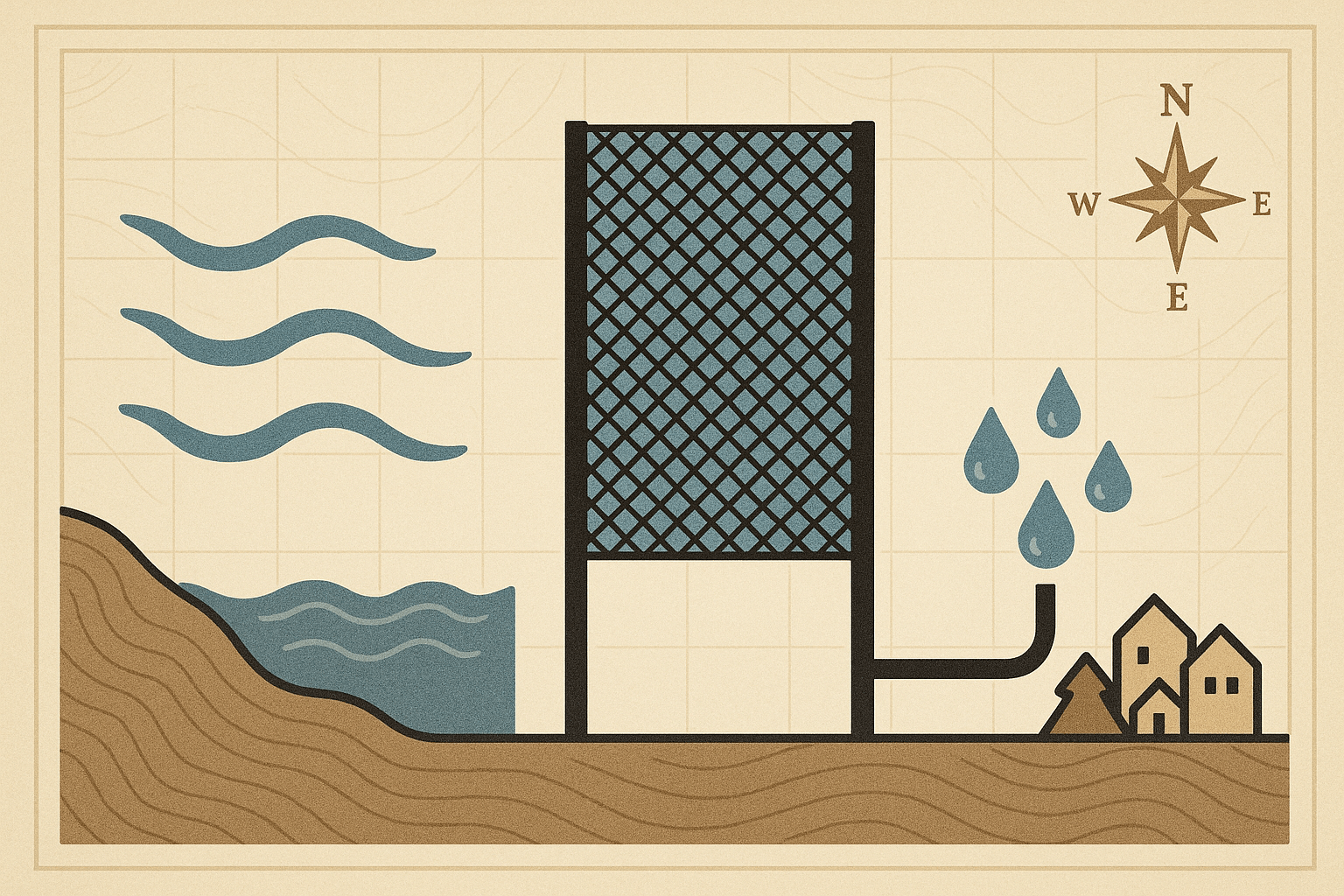

Harvesting the Mist: The Ingenious “Atrapanieblas”

For centuries, indigenous peoples and even native plants have found ways to draw moisture from the Camanchaca. But in recent decades, scientists and local communities have perfected a simple yet brilliant technology to capture this water on a larger scale: the fog catcher, or atrapanieblas.

A fog catcher is a deceptively simple structure. It consists of a large, rectangular frame, typically made of wood or metal poles, across which a fine mesh net is stretched taut. The material of choice is often a plastic mesh, like polypropylene Raschel mesh, which is durable and highly efficient at collecting water droplets.

The geography of their placement is critical for success. They are strategically installed on mountain ridges and hillsides facing the prevailing onshore winds, usually at altitudes between 700 and 1,000 meters where the Camanchaca is thickest and most consistent. As the dense fog is forced through the mesh:

- The tiny water droplets collide with the fibers of the net and stick to them.

- Through a process called coalescence, these tiny droplets merge, forming larger, heavier drops of water.

- Gravity takes over, pulling the heavy drops down the vertical strands of the mesh.

- At the bottom of the net, a gutter or trough collects the steady trickle of water.

- From the trough, a system of pipes channels the captured water into large storage tanks, ready for use by the community.

A single large fog catcher, measuring around 40 square meters, can harvest an average of 200 liters of water per day, with some days yielding over 1,000 liters during peak fog season.

A Lifeline for Arid Communities

For isolated settlements in the Atacama, like the village of Chungungo in the Coquimbo region, this technology has been revolutionary. Before the installation of a large-scale fog-catching system in the late 1980s, Chungungo’s 350 residents relied entirely on water being trucked in once a week, at great expense and with severe limitations.

The clean, fresh water harvested from the Camanchaca transformed the community. It provided a reliable source for drinking, cooking, and sanitation, dramatically improving public health. But the impact went further, breathing new life into the landscape itself. The water has been used for:

- Reforestation: Allowing villagers to plant trees that, in a beautiful feedback loop, can capture even more moisture from the fog themselves.

- Small-scale Agriculture: Supporting family gardens and enabling the cultivation of produce in a place where nothing grew before.

- Economic Innovation: The water has even spurred new industries. In Peña Blanca, a local brewery uses fog-catcher water to produce “Atrapaniebla”, a craft beer that is a testament to the region’s unique geographical resources.

The fog catchers of the Atacama are a powerful example of human-environment interaction. They represent a sustainable, low-cost solution born from a deep understanding of local geography. By observing the natural phenomena of their unique landscape—the currents, the winds, and the fog—the people of the Atacama have learned not just to survive, but to create an oasis of life in one of the most challenging environments on the planet.