The Geography of Isolation: Why the Middle of Nowhere?

To understand Baikonur, you must first understand the Kazakh Steppe. This immense, flat, and sparsely populated expanse covers nearly a third of Kazakhstan. For Soviet military planners in the 1950s, this seemingly empty landscape was a perfect canvas for their most ambitious and secret project. The choice of location was a masterclass in strategic geography, driven by three key factors:

- Vast, Empty Downrange: Rockets aren’t single-use monoliths; they shed stages as they climb. The Baikonur Cosmodrome has a clear, unpopulated flight path stretching for thousands of kilometers to the east, across the steppe and Siberia. This meant spent rocket boosters could fall back to Earth without endangering towns or cities.

- Cold War Secrecy: In the high-stakes environment of the Cold War, hiding a 6,717 square kilometer (2,593 sq mi) facility was paramount. The remote location, far from prying eyes and international borders, provided an ideal cloak of invisibility. In fact, the Soviets initially used a decoy name, referencing a small mining town named Baikonur hundreds of kilometers away to mislead the West.

- The Power of Latitude: Earth’s rotation provides a natural boost to rockets launching eastward. The closer a launch site is to the equator, the greater this rotational “slingshot” effect, saving precious fuel. At roughly 46° North latitude, Baikonur is not as ideal as America’s Cape Canaveral (28.5° N), but it was the most southerly practical location within the Soviet Union’s borders, offering a significant advantage for reaching critical orbits.

This combination of physical geography—flatness, emptiness, and favorable latitude—made this corner of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic the undisputed heart of the Soviet space program.

A City for Space: The Human Geography of a Monotown

A massive technical complex like a cosmodrome cannot exist in a vacuum. It requires thousands of scientists, engineers, technicians, and soldiers. To support the facility, the Soviets built a city from scratch right on the banks of the Syr Darya river. Initially called Leninsk, this settlement is now known as the city of Baikonur.

Baikonur is a classic example of a Soviet monotown (моногород)—a city whose entire economic and social existence revolves around a single industry. In its heyday, it was a privileged, closed city, supplied with goods unavailable elsewhere in the USSR, a reward for its crucial role. But today, its human geography is one of its most peculiar features.

Despite being deep inside the sovereign nation of Kazakhstan, the city of Baikonur is, for all practical purposes, Russian. It is administered by the Russian Federation. The Russian ruble is the official currency, the schools follow a Russian curriculum, and law and order are maintained by Russian police. The population of roughly 70,000 is a mix of Russian citizens working for Roscosmos (the Russian space agency) and Kazakh citizens, creating a unique cultural and jurisdictional bubble.

The Geopolitical Fault Line: A Soviet Relic in a New World

The entire dynamic of Baikonur was upended on December 26, 1991. When the Soviet Union dissolved, the political map of Eurasia was redrawn. Kazakhstan declared its independence, and suddenly, Russia’s premier spaceport and its sole facility for launching crewed missions was located in a foreign country.

This geographical and political predicament created an unprecedented challenge. For Russia, losing access to Baikonur was unthinkable. It would mean losing its independent human spaceflight capability overnight. For the newly independent Kazakhstan, the cosmodrome was a complex inheritance—a symbol of high technology and prestige on its soil, but also a costly, environmentally hazardous site operated by a foreign power.

The solution was a landmark geopolitical arrangement. In 1994, Russia and Kazakhstan signed a lease agreement. Russia formally leases the Baikonur Cosmodrome and the city of Baikonur from Kazakhstan. The current lease, extended in 2004, runs until 2050 at a cost of $115 million per year, in addition to Russia’s costs for maintaining the sprawling facility.

This has effectively created a geopolitical island. It is a territory where Russian law is enforced and Russian state functions are performed, all while existing within the recognized sovereign borders of Kazakhstan. This arrangement, while functional, is a source of periodic friction. Disputes arise over:

- Environmental Impact: Many older Russian rockets, like the workhorse Proton, use a highly toxic fuel called heptyl. Crashes and falling debris have led to environmental contamination, creating tension with Kazakh authorities and local populations.

- Lease Terms: The annual payment and the scope of Russian authority are subjects of ongoing negotiation and occasional political posturing.

- Sovereignty: For Kazakhstan, the presence of a large, Russian-administered zone on its territory is a constant and sensitive reminder of its colonial past and its complex relationship with its powerful northern neighbor.

Shifting Orbits: The Future of Baikonur

Recognizing the strategic vulnerability of relying on Baikonur, Russia has been actively working to secure its sovereign access to space. The most significant development is the construction of the Vostochny Cosmodrome, a new, state-of-the-art spaceport located in Russia’s own Far East, in the Amur Oblast.

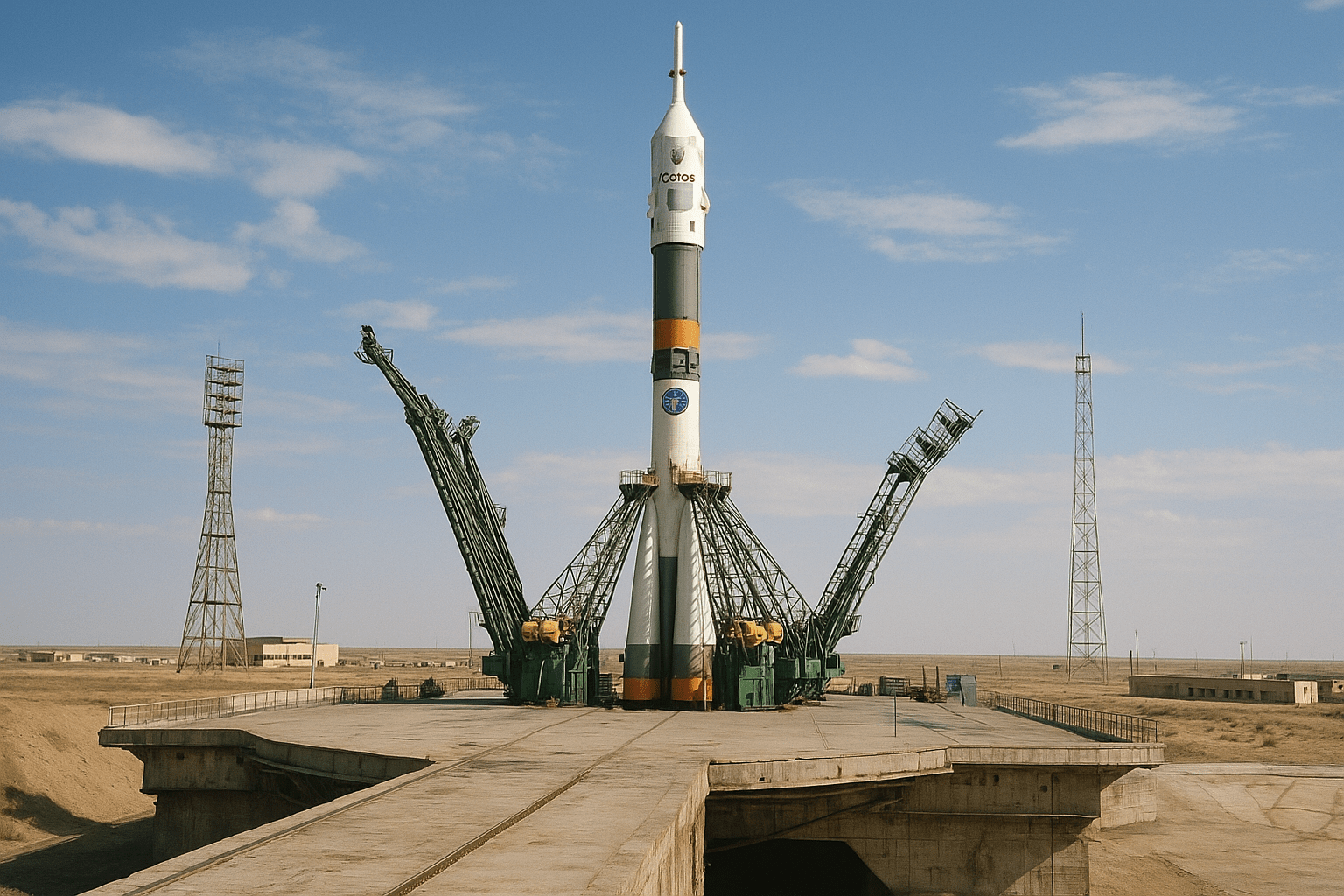

While construction has been slow and costly, Vostochny represents Russia’s long-term future. As more launch operations, particularly commercial and governmental satellites, shift to Vostochny, Baikonur’s role will inevitably change. It will likely remain the launch site for crewed missions to the International Space Station for the foreseeable future, due to its existing infrastructure and Soyuz rocket certification.

Kazakhstan, for its part, is not content to remain a passive landlord. The country is pursuing its own space ambitions, often in partnership with Russia. The “Baiterek” joint venture aims to bring newer, more environmentally friendly Russian rockets (like the upcoming Soyuz-5) to Baikonur, giving Kazakhstan a direct stake in future launch operations.

The Baikonur Cosmodrome is more than a collection of launchpads. It is a living artifact of the 20th century, a place where the physical geography of the steppe met the geopolitical ambitions of a superpower. Today, it stands as a unique anomaly on the world map—a Russian spaceport adrift in Kazakhstan, navigating the gravitational pull of history, national identity, and the relentless march toward the future.