Picture the Baltic region: a trio of nations—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—huddled together on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea. To the outside world, they often seem like a matched set. They share a similar recent history of heroic independence, a love for dense rye bread, and stunning coastlines dotted with pine forests. If you drive from Lithuania’s capital, Vilnius, through Latvia’s Riga, and up to Estonia’s Tallinn, it feels like a seamless journey through a shared cultural landscape. So, you’d be forgiven for thinking they’re basically three siblings. But try asking a Latvian to have a chat with their Estonian neighbor in their native tongues. You’ll be met with a blank stare.

The truth is, while they are geographical siblings, two of them speak a related language, while the third speaks something from an entirely different linguistic universe. This is the great Baltic mix-up, a fascinating puzzle rooted deep in the human and linguistic geography of Europe.

The “Baltic” Name: A Geographical Shortcut

First, let’s clear up why we even group them together. The term “Baltic States” is a geopolitical and geographical convenience, not a linguistic or ethnic one. All three nations border the Baltic Sea, which has shaped their climate, trade, and history for centuries. Their more recent history has been tragically intertwined. All three were absorbed into the Soviet Union after World War II and regained their independence with the powerful, non-violent “Singing Revolution” in the late 1980s and early 1990s. They all joined the European Union and NATO together in 2004.

This shared experience forged a powerful bond and a unified identity on the world stage. From a human geography perspective, they are a bloc. They vote together, they stand together against regional threats, and their economies are increasingly integrated. But this modern-day alliance glosses over a much, much older story—a story told not in political treaties, but in grammar and vocabulary.

Two Language Families, One Neighborhood

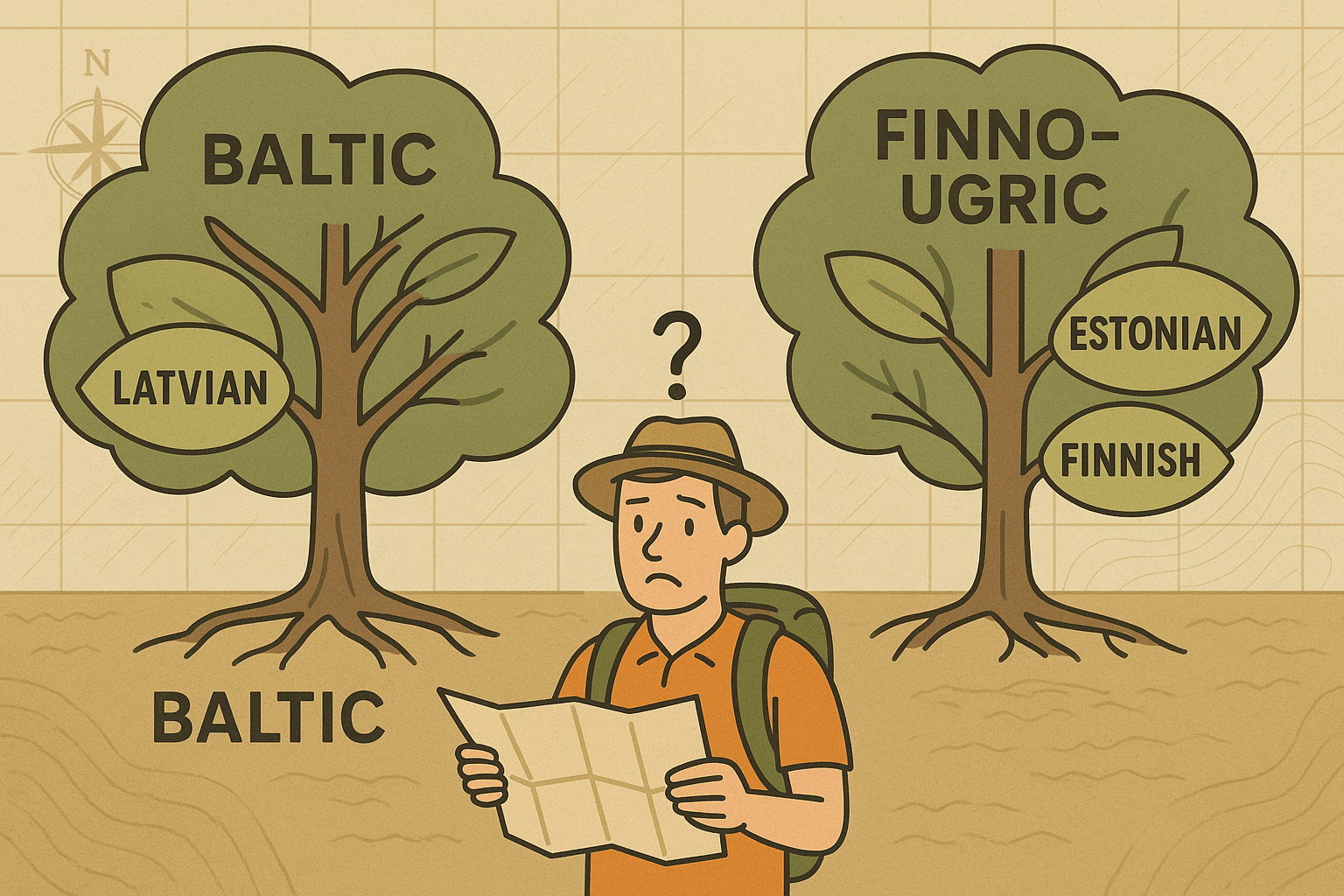

The core of the confusion lies in two completely separate language “family trees” that happen to have grown right next to each other. Think of it like having a pine tree and a maple tree in the same small yard. They share the same soil and weather, but they are fundamentally different species.

The Balts: Latvian and Lithuanian

Latvian and Lithuanian belong to the Baltic language branch of the vast Indo-European family. This is the same massive family that includes English (Germanic), French (Romance), and Russian (Slavic). The Baltic branch is a tiny, ancient, and incredibly special twig on this family tree. In fact, Latvian and Lithuanian are the only two surviving Baltic languages in the world (a third, Old Prussian, died out in the 18th century).

A Latvian listening to a Lithuanian speaker won’t understand everything, but they’ll catch the rhythm, recognize many root words, and get the general gist. It’s a bit like a Spanish speaker listening to Italian—the connection is undeniable.

- Hello: “Sveiki” (Latvian) vs. “Sveikas” (Lithuanian)

- One, Two, Three: “Viens, divi, trīs” (Latvian) vs. “Vienas, du, trys” (Lithuanian)

- Man: “Vīrs” (Latvian) vs. “Vyras” (Lithuanian)

Interestingly, Lithuanian is considered by linguists to be one of the most conservative, or “oldest”, living Indo-European languages. It retains grammatical features that other languages lost thousands of years ago, making it incredibly valuable for studying the roots of all Indo-European tongues, including English!

The Odd One Out: Estonian’s Finno-Ugric Roots

And then there’s Estonia. Estonian is not a Baltic language. It’s not even an Indo-European language. It belongs to a completely separate family called the Finno-Ugric languages (which is part of the larger Uralic family, with roots tracing back to the Ural Mountains region).

An Estonian listening to a Latvian is like an English speaker listening to Mandarin. There is zero mutual intelligibility. The grammar, vocabulary, and sounds are alien. Estonia’s closest linguistic relative isn’t its next-door neighbor Latvia, but Finland, just across the Gulf of Finland. Other, more distant relatives include Hungarian and the Sámi languages of northern Scandinavia.

Let’s compare Estonian to Latvian to see the stark difference:

- Hello: “Sveiki” (Latvian) vs. “Tere” (Estonian)

- Thank you: “Paldies” (Latvian) vs. “Aitäh” (Estonian)

- One, Two, Three: “Viens, divi, trīs” (Latvian) vs. “Üks, kaks, kolm” (Estonian)

- Head: “Galva” (Latvian) vs. “Pea” (Estonian)

The difference is immediate and absolute. The Estonian “üks, kaks, kolm” sounds much more familiar to a Finn (“yksi, kaksi, kolme”) than to their immediate southern neighbor. This linguistic border between Latvia and Estonia is one of the sharpest in all of Europe.

Why the Confusion? A Story of Proximity and Power

So, how did these two wildly different language groups end up as such close neighbors? The answer is a story of ancient migrations. The ancestors of the Finno-Ugric peoples (Estonians, Finns) and the ancestors of the Balts (Latvians, Lithuanians) settled in this corner of Europe thousands of years ago, long before modern nations existed. They established their territories, and the linguistic map was drawn.

Over the centuries, despite the language barrier, they were subject to the same geopolitical forces. German crusading knights (the Teutonic Order) dominated the region in the Middle Ages, establishing cities like Riga and Tallinn and creating a German-speaking ruling class. This is why the old towns of both capitals share a distinctly Germanic, Hanseatic architectural style. Later, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Swedish Empire, and ultimately the Russian Empire and Soviet Union washed over them, imposing their own languages as tools of administration and power.

Because of this shared history and geography, the cultures have converged in many ways. This phenomenon, where unrelated languages spoken in a shared area start to influence each other’s grammar and vocabulary, is known to linguists as a sprachbund. All three nations share a love for song festivals, a culinary tradition based on pork, potatoes, and dark rye bread, and a certain stoic, nature-loving temperament. They’ve borrowed words from German and Russian. But at their core, the linguistic DNA remains worlds apart.

The Baltic Puzzle Solved

So, the next time you hear someone refer to the “Baltic countries”, you’ll know the secret they’re hiding. It’s a convenient label for a trio of proud, resilient nations on the Baltic coast, but it masks a deep and fascinating linguistic divide.

Latvians and Lithuanians are the last of the Balts, speaking the ancient echoes of a unique Indo-European branch. Estonians, meanwhile, look north across the sea to their Finnish cousins, speaking a language with an entirely different rhythm and soul. It’s this very diversity, packed into such a small and beautiful corner of Europe, that makes the region so compelling. It’s not a mix-up; it’s a rich, living tapestry of geography and history, waiting to be explored.