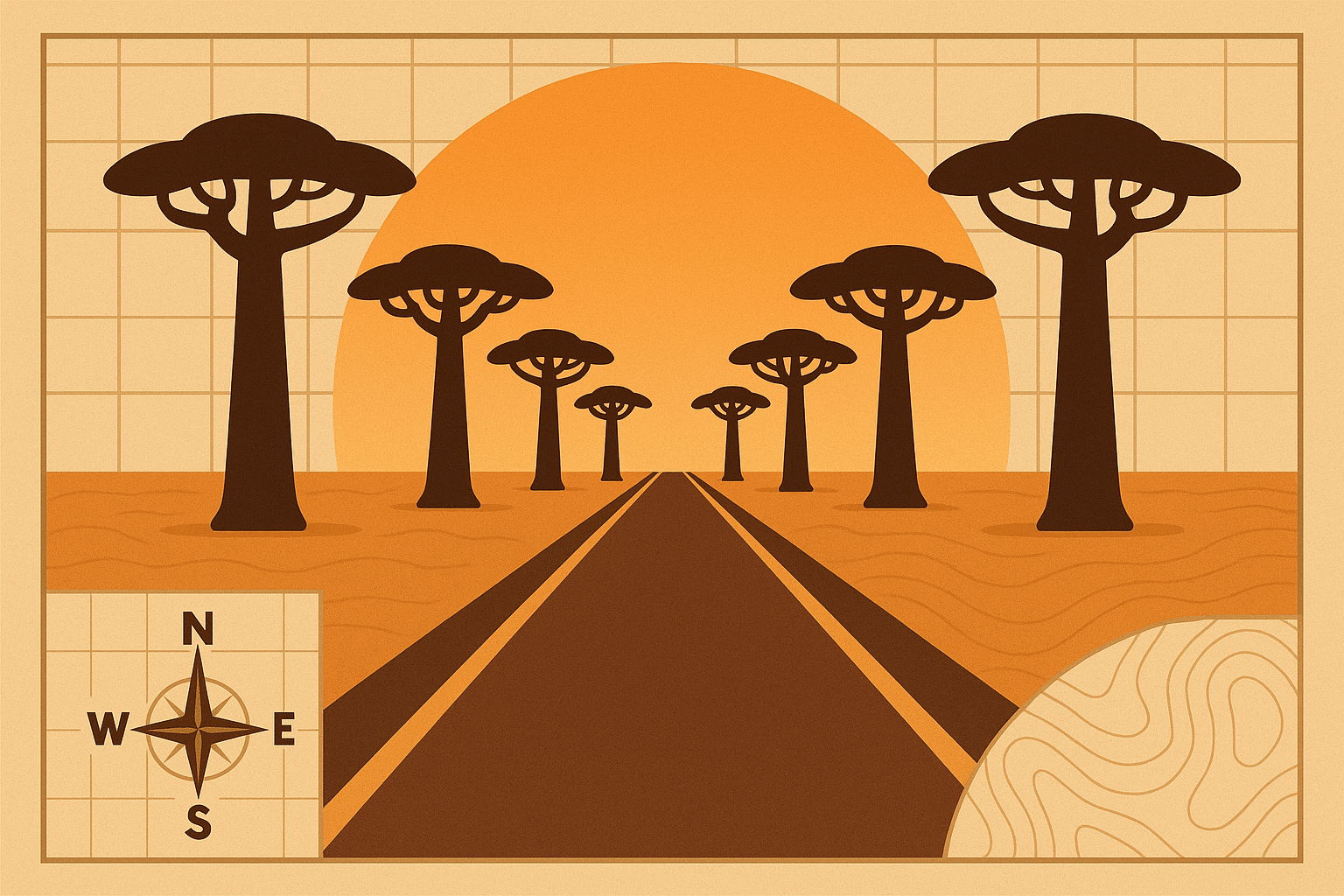

Imagine a dusty, red-earth road flanked by colossal sentinels. Their smooth, massive trunks soar up to 30 meters (nearly 100 feet) into the sky, crowned by a tangle of branches that look more like roots, as if the trees were unceremoniously plucked from the heavens and planted upside-down. This is the Avenue of the Baobabs, or Allée des Baobabs, an otherworldly landscape in western Madagascar that has become an enduring symbol of the island nation.

Located on the RN8 dirt road connecting Morondava to Belon’i Tsiribihina, this collection of majestic trees is more than just a stunningly photogenic spot. It’s a living museum, a geographical anomaly, and a profound testament to the complex and often fraught relationship between humanity and the natural world. To understand the Avenue of the Baobabs is to read a story written on the land itself—a story of ecology, deforestation, and deep-seated cultural reverence.

A Landscape Forged by Absence

The first question that strikes any visitor is one of spatial significance: why are these giant trees, and so many of them, clustered here in this specific formation? The answer is both simple and startling. The “avenue” was never planted; it was revealed. These trees, predominantly the Adansonia grandidieri species—the largest of Madagascar’s six endemic baobabs—did not always stand in stark isolation against a flat, scrubby landscape. For centuries, they were integral members of a dense, dry deciduous forest.

The landscape you see today is a ghost of that former ecosystem. Over generations, Madagascar’s growing population cleared vast tracts of forest for agriculture, primarily for rice paddies and zebu cattle grazing. The traditional practice of slash-and-burn agriculture, known locally as tavy, transformed the region. Yet, amid this widespread deforestation, the baobabs remained.

They were spared for a combination of practical and spiritual reasons. Baobabs are poor sources of timber, their wood being spongy and water-logged. More importantly, they hold a sacred place in Malagasy culture. To cut one down would be to defy the ancestors and invite misfortune. The result is a relic landscape—an accidental avenue created not by planting, but by subtraction. The trees are the last survivors, silent witnesses to the forest that once surrounded them.

The Sacred Giants: A Story of Human Geography

The survival of the baobabs is a direct reflection of their importance to the local Sakalava people. In Malagasy cosmology, these ancient trees, some of which are over 800 years old, are not merely plants. They are revered as living ancestors, vessels for spirits, and intermediaries between the earthly and the divine. Local folklore is rich with stories about them, including the famous tale of why they look “upside-down”: angry gods, displeased with the trees’ vanity, ripped them from the ground and replanted them with their roots in the air.

This spiritual significance has tangible geographical outcomes. The trees serve as community landmarks and places of worship. Offerings of rum, honey, or candy are often left at their bases to appease the spirits and ask for blessings, such as a good harvest or the birth of a child.

Beyond their sacred role, the baobabs have immense practical value:

- Fruit: The large, gourd-like fruit contains a chalky pulp rich in Vitamin C, calcium, and antioxidants. Known as “monkey bread”, it’s a vital food source that can be eaten fresh or made into a nutritious drink.

- Seeds: The seeds are pressed to produce a valuable oil used for cooking and cosmetics.

- Bark: The thick, fibrous bark can be harvested sustainably without killing the tree. It is used to make durable rope, baskets, and even roofing material.

A few kilometers away from the main avenue lies another testament to this cultural connection: the “Baobab Amoureux” or Baobabs of Love. Here, two massive Adansonia za baobabs have twisted around each other in a permanent embrace over centuries. This unique site has become a pilgrimage destination for couples seeking a strong and lasting relationship, a perfect example of how physical geography becomes imbued with human meaning and tradition.

The Future of a Natural Monument

The fame of the Avenue of the Baobabs has exploded in the age of social media, transforming it from a local landmark into a global icon. This brings both vital opportunities and significant challenges. Tourism provides a much-needed source of income for the local communities, funding guides, craft markets, and small enterprises. It also raises global awareness about the unique biodiversity of Madagascar and the threats it faces.

However, the influx of visitors poses a risk to the very landscape they come to admire. Unregulated foot traffic can compact the soil around the trees’ shallow root systems, hindering water absorption. The demand for souvenirs can put pressure on local resources, and the carbon footprint of international travel is a growing concern for this fragile environment.

Recognizing its ecological and cultural value, the Madagascar government declared the Avenue a protected area in 2007, and it is now the center of the Menabe Antimena Protected Area. Conservation efforts are underway to manage tourism sustainably, reforest surrounding areas with native species, and work with local communities to ensure they benefit directly from protecting their natural heritage. The challenge is to balance preservation with the economic needs of a population living in one of the world’s poorest countries.

The Avenue of the Baobabs is, therefore, far more than a beautiful vista. It is a powerful lesson in geography, illustrating how human actions can radically reshape an environment. It’s a symbol of what has been lost, but also of what has been cherished and saved. As the sun sets behind their magnificent silhouettes, casting long shadows across the red earth, these ancient trees stand not just as a wonder of the natural world, but as a hopeful monument to the enduring power of culture to preserve life.