A Geologic Heresy

For decades, the Scablands were a profound mystery. The landscape is a chaotic jumble of exposed basalt bedrock, crisscrossed by immense, dry canyons (known as coulees), dotted with strange gravel bars, and scarred by features that defied explanation. In the early 20th century, the prevailing geologic doctrine was uniformitarianism—the idea that the Earth’s features were shaped by slow, gradual processes over immense spans of time. A river slowly carving a canyon over millions of years made sense. The Scablands did not.

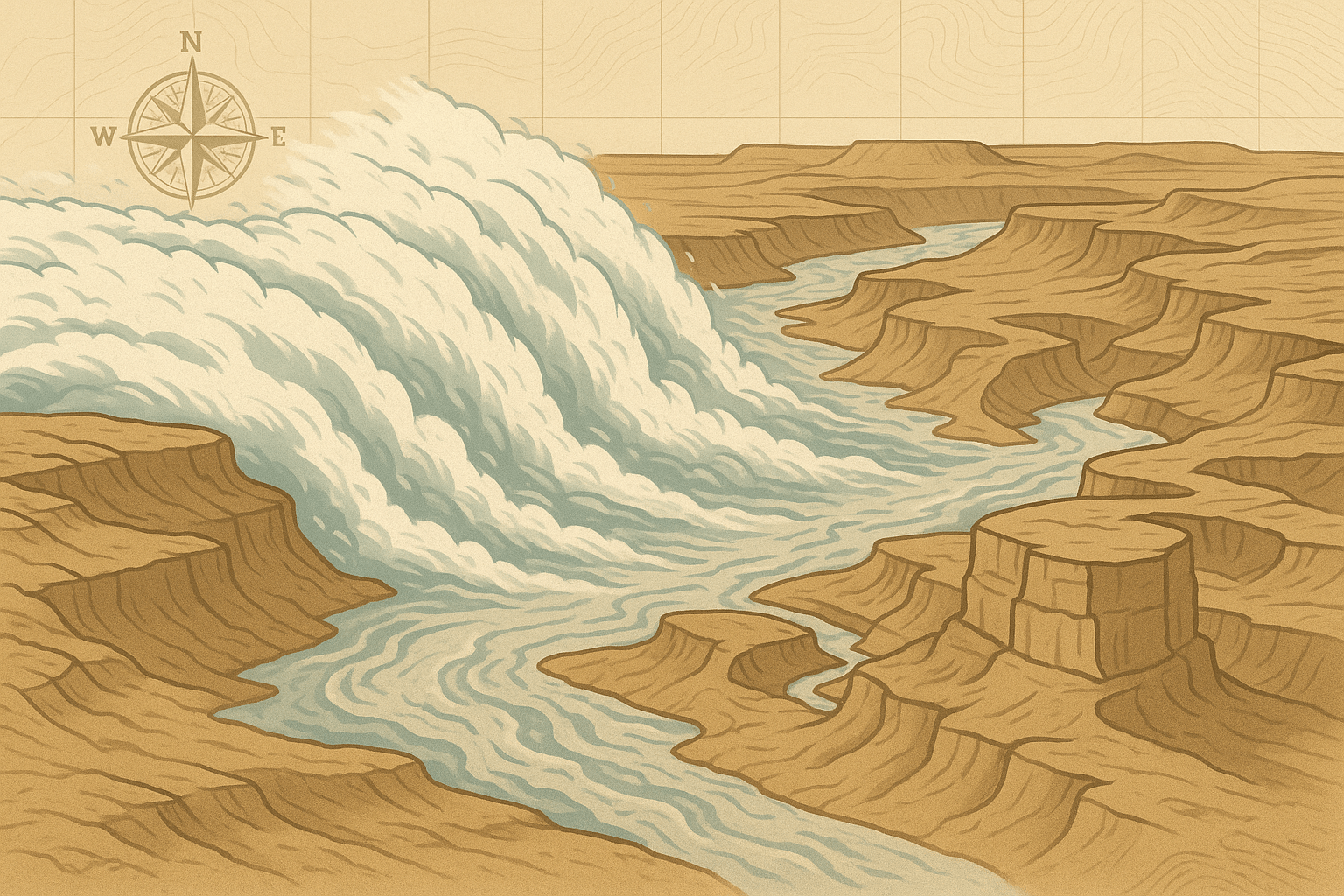

Then, in the 1920s, a geologist named J Harlen Bretz proposed a theory so radical it was deemed scientific heresy. After years of meticulously mapping the region, he saw evidence not of slow erosion, but of a single, cataclysmic event. He pointed to giant, dry waterfalls, house-sized boulders dropped miles from their origin, and colossal ripple marks etched not in sand, but in solid ground. His conclusion? This entire landscape was carved in a matter of days by a flood of unimaginable scale. The scientific community ridiculed him, calling his “Spokane Flood” hypothesis an “outrageous theory.” Bretz, lacking a plausible source for such a colossal amount of water, would have to wait decades for his vindication.

The Culprit: A Lake the Size of a Sea

The source of the floodwaters lay hidden over 500 miles away, in what is now Montana. During the last Ice Age, the Cordilleran Ice Sheet crept down from Canada. A massive finger of this ice, the Purcell Lobe, advanced across the Clark Fork River valley, forming a towering ice dam nearly 2,500 feet high.

Behind this dam, the waters of the Clark Fork River began to pool. With no outlet, the water rose and rose, creating an enormous glacial lake: Glacial Lake Missoula. At its peak, this temporary lake was immense, covering 3,000 square miles of western Montana and holding an estimated 500 cubic miles of water—as much as Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined. The modern city of Missoula, Montana, would have been under 950 feet of water.

The Outburst Flood: Unleashing Hell

An ice dam, unlike a concrete one, is inherently unstable. As the water in Glacial Lake Missoula deepened, the immense pressure at the base of the dam began to lift the ice. Water forced its way into cracks and fissures, and the dam’s structural integrity began to fail. Suddenly, and catastrophically, it gave way.

The result was an “outburst flood” of incomprehensible power. A 2,000-foot-tall wall of water, ice, and debris burst forth, thundering across Idaho, Washington, and down into Oregon at speeds up to 80 miles per hour. This was not merely water; it was a liquid abrasive, carrying billions of tons of rock and sediment. It stripped away hundreds of feet of topsoil and loess in hours, exposing the hard volcanic basalt beneath. The deep, rich soils of the Palouse region were scoured away, leaving behind the stark, rocky “scablands” that Bretz had studied.

Geologists now believe this cycle repeated itself dozens of times over a period of 2,000 years. As the ice sheet advanced, it would dam the river, the lake would fill, and the dam would inevitably burst again, sending another titanic flood across the Pacific Northwest.

A Landscape Forged in Chaos

Walking through the Channeled Scablands today is like visiting a crime scene frozen in time. The evidence of this violent past is everywhere, sculpted on a scale that is difficult to process from ground level. From a satellite view, however, the immense channels scoured into the earth become terrifyingly clear.

Dry Falls: A Ghost of Niagara

The most spectacular relic is Dry Falls. Today, it’s a stunning 3.5-mile-wide, 400-foot-high series of basalt cliffs. During the floods, however, this was a waterfall of epic proportions. Water poured over this precipice at an estimated 65 miles per hour, creating a cataract that would have dwarfed Niagara Falls many times over. It was the largest waterfall known to have ever existed on Earth.

Giant Current Ripples

Near the city of Missoula and across the Camas Prairie, you can find ripple marks. But these aren’t the gentle ripples you see on a sandy beach. These are giant current ripples, some as high as 30 feet and spaced 500 feet apart. Formed in deep, fast-moving water, they are definitive proof of the immense volume and velocity of the floodwaters that created them.

Erratic Boulders and Coulees

Throughout the Scablands and down into Oregon’s Willamette Valley, you’ll find “erratics”—boulders, some the size of a small house, composed of rock types that are geologically foreign to the area. These massive stones were encased in icebergs that broke off the ice dam, floated along on the floodwaters for hundreds of miles, and were unceremoniously dropped as the icebergs melted. The largest of these canyons, the Grand Coulee, is a 50-mile-long, 900-foot-deep chasm carved from solid rock by the flood.

The Flood’s Human Legacy

The Missoula Floods didn’t just create a unique physical geography; they profoundly shaped the human geography of the Pacific Northwest. The floods scoured fertile soil from eastern Washington, creating the less-arable Scablands. But where did that soil go? It was deposited downstream, creating the incredibly rich and productive agricultural lands of the Willamette Valley in Oregon and the Pasco Basin in Washington.

Modern engineering has even harnessed the flood’s creations. The Grand Coulee Dam, one of the largest concrete structures in the world, was built within the massive channel carved by the ancient floodwaters, a testament to humanity’s ability to build upon the awesome power of nature.

Decades after he first proposed his theory, new evidence of the glacial lake and the physics of ice dam failures finally vindicated J Harlen Bretz. His “outrageous” idea is now the accepted explanation for one of Earth’s most dramatic landscapes. The Channeled Scablands stand as a powerful reminder that our planet’s history is not just a slow, steady march, but is punctuated by moments of unimaginable, landscape-altering catastrophe.