Scattered along coastlines in places like Madagascar, Egypt, and Australia are gargantuan, V-shaped dunes. For years, the prevailing scientific consensus labelled them as eolian, or wind-formed, features. But a group of scientists is challenging that notion, proposing a far more cataclysmic explanation: that these are the deposits left behind by prehistoric megatsunamis, triggered by oceanic comet or asteroid impacts.

A Geographical Puzzle Carved in Sand

To understand the debate, we first have to appreciate the sheer scale of these formations. These are not your typical beach dunes. The most famous examples, the Fenambosy Chevrons in southern Madagascar, are colossal. Each “arm” of the V can be several kilometers long, with the dunes rising up to 200 meters (over 650 feet) above sea level. Most strikingly, they are located as far as 5 kilometers (3 miles) inland.

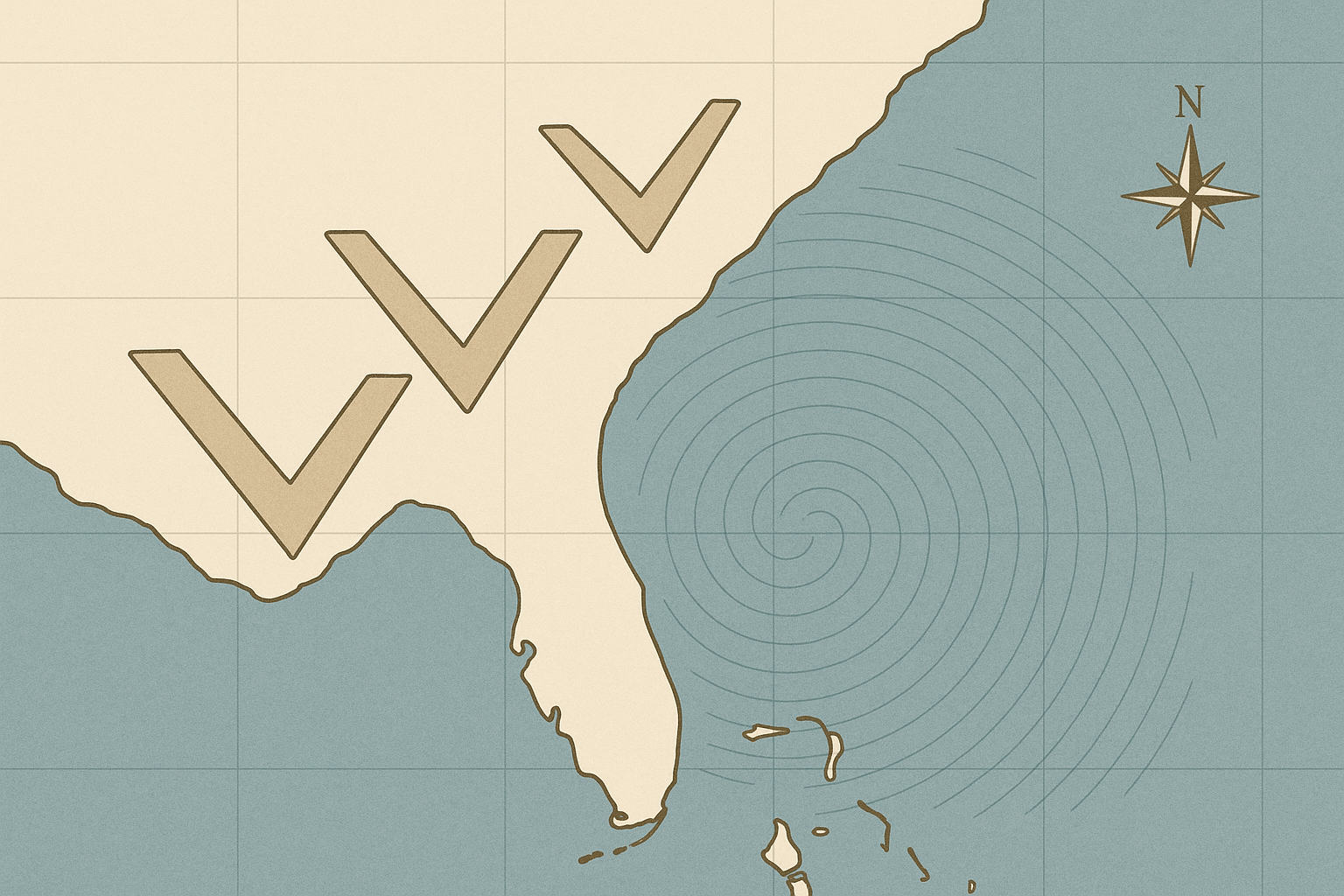

The “V” shape is consistent, with the point of the V always aimed inland. In Madagascar, the four major chevron fields all point north-northwest. It’s as if a monstrous force surged from the southeast, out of the Indian Ocean, and slammed into the island, leaving these deposits as its calling card.

For a long time, geologists classified them as parabolic dunes, which are U-shaped or V-shaped sand formations created by strong, persistent winds pushing sand inland, often anchored by vegetation. But the size, composition, and orientation of the chevrons have led some to look for a more extraordinary cause.

The Megatsunami Hypothesis: Evidence of Impact?

The primary proponents of the megatsunami theory are the Holocene Impact Working Group (HIWG), a team of interdisciplinary researchers led by geophysicist Dallas Abbott. Their hypothesis is that a major impact event in the Indian Ocean, roughly 5,000 years ago, generated a wave of almost unimaginable power.

They believe they have found the smoking gun: a feature on the ocean floor known as the Burckle Crater. Located about 1,500 kilometers southeast of Madagascar, this 29-kilometer-wide depression lies 3,800 meters below the surface. Abbott and her team argue that its features are consistent with an impact crater.

The evidence connecting this potential impact to the chevrons on land is multifaceted:

- Orientation: The chevrons in Madagascar and Western Australia point directly away from the location of the Burckle Crater, like splash marks radiating from a central point of impact.

- Composition: This is perhaps the most compelling piece of evidence. The sand within the chevrons is not just local, terrestrial sand. It contains a bizarre mix of oceanic material. Scientists have found marine microfossils, like foraminifera and diatoms, that you would only expect to find on the deep ocean floor.

- Exotic Materials: More tellingly, some of these tiny marine fossils are fused with flecks of metal—nickel, chromium, and iron—which are common in cosmic bodies like comets but rare in Earth’s crust. This fusion suggests an event involving incredible heat and pressure, consistent with an oceanic impact that vaporized the impactor and ejected a plume of superheated water, steam, and sediment.

- Scale and Reach: Proponents argue that wind simply doesn’t have the power to lift vast quantities of deep-sea sediment and deposit it hundreds of feet high, miles inland. A megatsunami, however, could. Computer models suggest a Burckle-sized impact could create a tsunami over 200 meters high at its source, a wave that would barely lose energy as it crossed the open ocean.

The Mainstream View: Just Wind and Time

As compelling as the megatsunami story is, it remains a fringe theory for most of the geological community. Mainstream science overwhelmingly favors the eolian, or wind-based, explanation. Geologists like Jody Bourgeois at the University of Washington argue that there is no need for a cataclysmic event to explain the chevrons.

The counterarguments are strong:

- Parabolic Dunes: The V-shape is a well-understood feature of parabolic dunes. Strong coastal winds can blow sand inland, and where vegetation anchors the “arms” of the dune, the less-vegetated center moves faster, creating the characteristic V-shape pointing downwind.

- Questionable Crater: The existence of Burckle Crater as an impact site is itself heavily debated. Many geologists believe it’s a tectonic feature, like an abyssal plain or a feature formed by seafloor spreading, not a crater. Without a confirmed impact, the linchpin of the megatsunami theory falls apart.

- Sediment Source: Critics suggest the marine fossils within the dunes could come from older, uplifted coastal plains or ancient seabeds that are now exposed on land. Over millennia, wind could have eroded these fossil-rich rocks and incorporated the material into the dunes.

The scientific community demands extraordinary evidence for extraordinary claims, and for many, the megatsunami hypothesis hasn’t yet met that high bar. The debate highlights a fundamental tension in science between uniformitarianism (the idea that Earth is shaped by slow, gradual processes) and catastrophism (the idea that sudden, violent events play a key role).

Echoes in Human History?

If we entertain the possibility of an impact around 2800 BCE, the human geography implications are staggering. This was not a desolate, empty period of prehistory. It was the dawn of civilization. The Sumerian, Egyptian, and Indus Valley civilizations were all flourishing. An event that could reshape coastlines in the Indian Ocean would have been a global catastrophe, causing climate disruption, darkened skies, and unimaginable devastation for any coastal populations.

Some researchers have speculatively linked this potential event to the proliferation of flood myths found in cultures worldwide, from the Epic of Gilgamesh to the story of Noah. While a direct link is impossible to prove, the timing is tantalizing. Could these chevrons be the physical evidence of a real-world event that was passed down through generations as legend?

A Landscape Whispering Secrets

Today, the chevrons remain silent monuments to a fierce debate. Are they the slow, patient work of wind and sand over millennia? Or are they the colossal scars from a day when the ocean rose up to meet the sky, a tangible link to one of the most violent events in recent geological history?

Whether formed by wind or water, these landforms are a humbling reminder of the immense power of the natural world. They challenge us to read the landscape, to question our assumptions, and to listen for the secrets the Earth is whispering.