At its heart, a country is a political and geographical entity, but what gives it legitimacy? To a geographer, a country isn’t just about land and borders; it’s about power, identity, and global relationships. The question “What is a country?” plunges us into the fascinating intersection of physical geography, human systems, and international law. Let’s break down the technical definition into simple, understandable parts.

The Official Blueprint: The Montevideo Convention

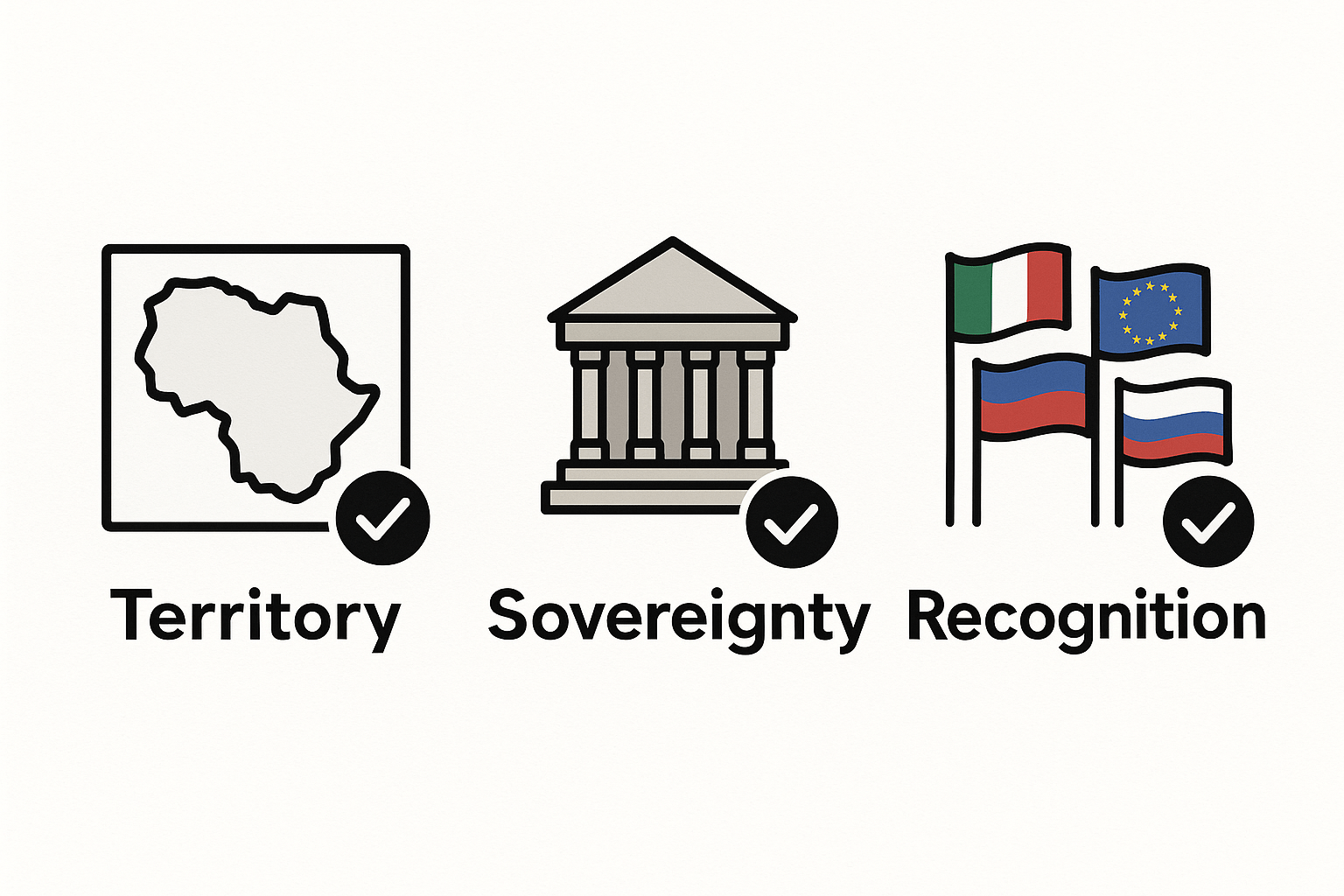

The most widely accepted framework for defining a country comes from the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, signed in 1933. While it’s a nearly century-old document originating from the Americas, its four key criteria have become the global standard for statehood. For an entity to be considered a state (the legal term for a country), it must possess:

- A defined territory

- A permanent population

- A government

- The capacity to enter into relations with other states

Let’s look at each one, because this is where the lines start to get blurry.

1. A Defined Territory

This seems simple enough. A country needs land with more-or-less defined borders. It needs a physical space on the Earth. However, “defined” is a flexible term. Many recognized countries have ongoing border disputes. India and Pakistan both claim the entire region of Kashmir, and Israel’s borders have been a subject of intense conflict for decades. The key is that there is a core, undisputed territory over which the state exercises control.

Size is irrelevant. Vatican City sits on just 0.44 square kilometers (about 110 acres) within Rome, making it the world’s smallest country. On the other end of the spectrum is Russia, sprawling across 11 time zones. Both, however, satisfy this territorial requirement.

2. A Permanent Population

A country needs people who live there on a permanent basis. It can’t just be a rotating cast of researchers or vacationers. This is why Antarctica, despite being a massive continent with defined boundaries and human presence, is not a country. Its inhabitants are scientists and support staff on temporary assignments. The size of the population doesn’t matter—the Pacific island nation of Tuvalu has around 11,000 citizens, while China has over 1.4 billion. As long as there’s a stable community, this box is checked.

3. A Government

To be a country, a territory needs a system of administration and control. There must be a government that runs the state, provides services, creates laws, and manages the economy. The type of government is not a factor in this criterion. Whether it’s a democracy, a monarchy, a communist state, or a dictatorship, its existence is what matters for the definition of a state.

This can get complicated in “failed states” where government control has collapsed due to civil war or anarchy, like Somalia during the 1990s and 2000s. However, even in these cases, the infrastructure of a state and its international identity usually persist, even if the government on the ground is ineffective.

The Dealbreaker: Sovereignty and International Recognition

The first three criteria are relatively straightforward. It’s the fourth one—the capacity to enter into relations with other states—that causes all the debate. This is the essence of sovereignty: a government’s absolute authority to rule its territory without any external interference.

But how do you prove you have this capacity? The primary way is through international recognition. If other countries treat you like a country—by establishing embassies, making trade deals, and signing treaties with you—then you are effectively a country. This is why the United Nations is so important. Being granted membership in the UN is the ultimate confirmation of statehood in the modern world. Currently, there are 193 UN member states. Adding the two non-member observer states, Vatican City and Palestine, brings the most common tally to 195 countries.

This is where our definition moves from a simple checklist to a complex web of global politics.

Case Studies: The Gray Areas of the World Map

The rules of the Montevideo Convention seem clear until you apply them to real-world geopolitical disputes.

Case Study: Taiwan

Taiwan is perhaps the most famous example of a “country that isn’t.” Let’s run it through the checklist:

- Defined Territory? Yes, the island of Taiwan and several smaller surrounding islands.

- Permanent Population? Yes, nearly 24 million people.

- Government? Absolutely. Taiwan has a robust, democratically elected, and independent government (the Republic of China, or ROC).

It checks all the first three boxes perfectly. The problem is sovereignty and recognition. The People’s Republic of China (PRC), which governs the mainland, claims Taiwan as a rogue province under its “One-China” policy. To maintain diplomatic and economic relations with the powerful PRC, most nations in the world, including the United States and the entire UN, officially recognize only one China—the one based in Beijing. Therefore, Taiwan cannot be a UN member and has formal diplomatic relations with only a dozen or so small nations. It is a de facto (in fact) sovereign state, but it lacks widespread de jure (by law) recognition.

Case Study: Kosovo

Kosovo unilaterally declared independence from Serbia in 2008. It has a territory, a population, and a government. But its sovereignty is hotly contested. Around 100 of the 193 UN members (including the US and most of Europe) recognize it as an independent country. However, Serbia, backed by powerful allies like Russia and China, still considers Kosovo a part of its own territory. Is Kosovo a country? It depends entirely on who you ask.

So, What’s the Final Tally?

There is no single correct answer, which is a frustrating but fascinating reality of political geography.

- 195 Countries: This is the most common answer. It includes the 193 UN member states plus the 2 UN observer states (Vatican City and Palestine). This is the count most geographers and world almanacs use.

- 197 Countries: This number includes the 195 above plus Taiwan and Kosovo, entities that have significant, albeit incomplete, recognition and function as independent states.

- 200+ Countries: If you start including self-proclaimed states with little to no recognition, like Somaliland, Transnistria, or Abkhazia, the number grows even larger. These entities often meet the first three Montevideo criteria but fail spectacularly on the fourth.

Ultimately, a country is more than lines on a map. It is a human construct, built on a delicate balance of land, people, government, and the crucial, often political, agreement of others. The world map is not static; it is a dynamic document that is constantly being redrawn by conflict, independence movements, and shifting global politics. And that makes the simple question of “What is a country?” one of the most complex and interesting in all of geography.