To an outsider, footage of the grind is shocking. The sea turns crimson as islanders on shore and in boats drive pods of pilot whales into a bay to be killed. The practice is condemned internationally as a cruel and unnecessary slaughter. Yet, to the Faroese, it is a centuries-old tradition, a source of community sustenance, and an integral part of their identity. To truly understand the grind, we must look beyond the immediate controversy and examine it through the lens that has shaped the Faroese people more than any other: geography.

The Geographical Stage: A Land of Fiords and Scarcity

The Faroe Islands are the tips of a submerged volcanic ridge in the middle of a vast, unforgiving ocean. Their very existence is a testament to powerful geological forces. This geography dictates every aspect of life, and it created the perfect conditions for the grind to develop.

- The Fiords as Natural Traps: The defining feature of the Faroese landscape is its fiords (or fjords). These long, narrow, deep inlets of the sea, carved by glaciers, are flanked by towering cliffs. For migrating pods of long-finned pilot whales, these fiords can become natural funnels. Once a pod enters a fiord, its path inland becomes progressively narrower, making it possible for small boats to guide them towards a designated shoreline. Without these specific topographical features, the entire method of the grind would be impossible.

- A Climate of Scarcity: The Faroes sit at a latitude of 62° North. The climate is subpolar oceanic—cool, wet, cloudy, and relentlessly windy. This weather, combined with the rocky, steep terrain, makes agriculture incredibly difficult. Less than 2% of the archipelago’s land is arable. Historically, growing enough grain to survive was impossible. The land offered sheep for wool and meat, and some root vegetables, but it was never enough. The true larder of the Faroe Islands has always been the sea.

This stark reality of physical geography—abundant ocean resources next to barren land—meant that for centuries, survival was dependent on successfully harvesting from the sea. The ocean wasn’t just a resource; it was the primary source of life.

Human Geography: A Culture Forged in Isolation

Geography doesn’t just shape landscapes; it shapes societies. The remoteness of the Faroe Islands created a unique human geography defined by self-reliance and intense community bonds.

Historically, the islands were profoundly isolated. Trade was limited and unreliable. Communities, or bygdir, had to be almost entirely self-sufficient. This fostered a powerful ethos of communal effort. When a resource became available, whether it was a school of herring or, most significantly, a pod of whales (a grind), the entire community mobilized. Survival was a team sport, not an individual pursuit.

This principle is embedded in the Grindadráp. It is not a commercial enterprise. It is not a sport. It is a communal food drive, governed by ancient traditions and local regulations. When a pod is sighted, the news spreads like wildfire. A complex, non-hierarchical system kicks into gear. People leave their jobs, launch their boats, and take up their designated roles in a process that has been refined over generations.

The Hunt: An Intersection of People and Place

The grind itself is a masterclass in using local geographical knowledge. The process isn’t a chaotic chase; it’s a carefully managed herding event that relies on an intimate understanding of the coastal topography.

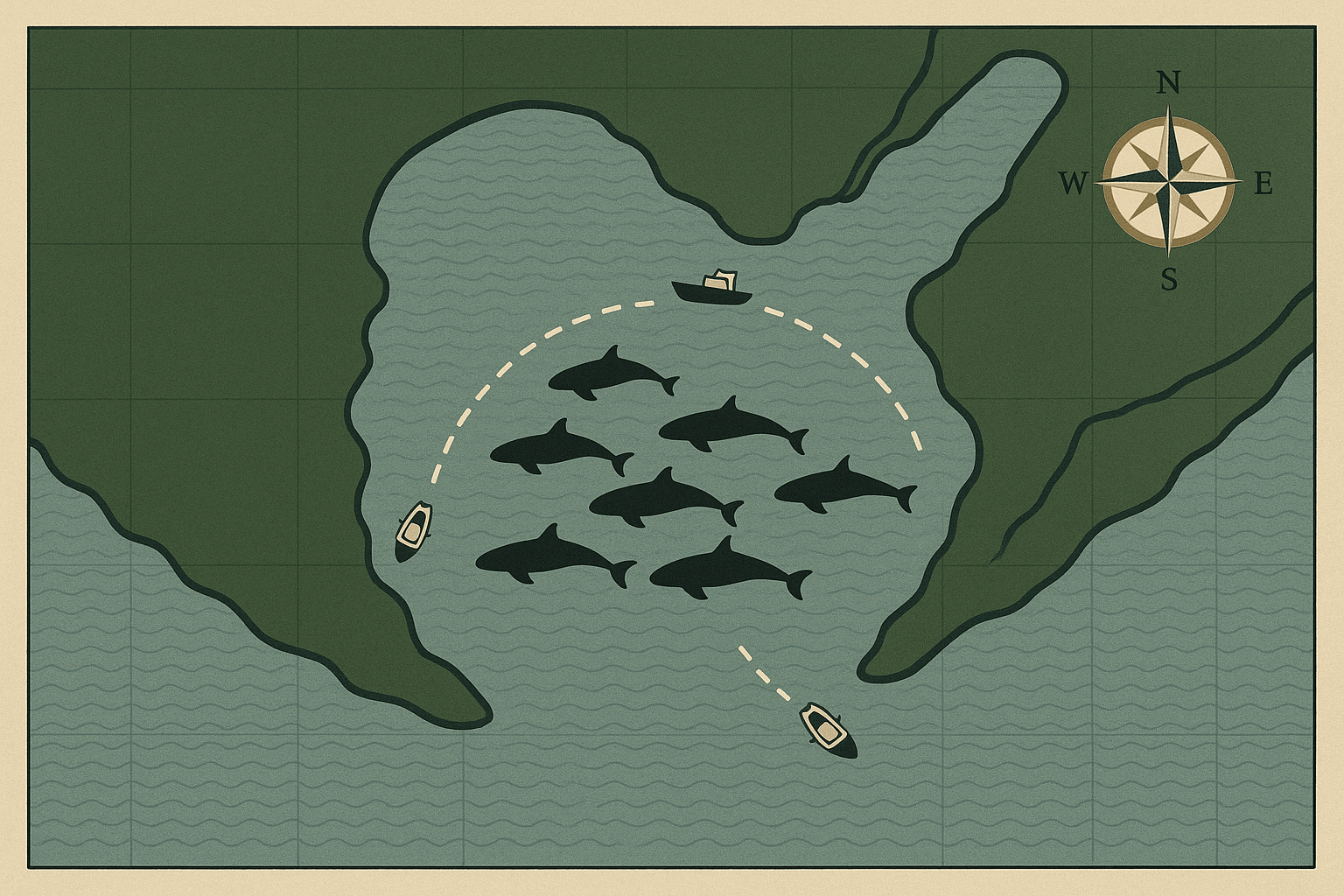

- Sighting and the Drive: A lookout spots a pod. The grindaboð, or call to the hunt, is issued. Boats form a wide semi-circle behind the pod, far out at sea. By tapping on the hulls and using the boat engines, they create a wall of sound that encourages the whales to swim away from them—towards land.

- The Designated Bays: The whales are not driven onto just any beach. The hunt is only permitted in 23 specific, officially authorized bays, known as hvalvágir. These bays are chosen for their specific geography: they have a gentle, sandy or fine-gravel slope that allows the whales to be beached quickly and securely. This specific landscape feature is crucial for the process.

- The Communal Distribution: After the kill, the district sheriff (sýslumaður) supervises the measurement of the catch. The meat and blubber are then distributed among the participants and the local community according to a centuries-old, documented system. Nothing is sold; it is a share of a communal harvest. This system of free, equitable distribution is a direct legacy of a time when this food was essential for staving off winter famine.

A Shifting Landscape: Modernity and Controversy

Of course, the geographical context of the Faroe Islands is no longer what it was. Globalization has reached its shores. Tórshavn, the capital, has supermarkets stocked with food from around the globe. High-speed internet connects islanders to the world, a world that is largely horrified by their tradition. The argument that the grind is essential for “survival” is now more complex.

For many Faroese, it remains a vital source of free, organic, local meat in a place where most other food must be imported at great expense. It’s also a powerful cultural touchstone, a link to their ancestors and a celebration of the community spirit that allowed them to thrive in this challenging place.

Ironically, a new and invisible geographical threat now challenges the tradition from within. Global ocean currents, which once brought only life-giving sustenance, now carry industrial pollutants. Mercury and PCBs accumulate in the marine food chain, concentrating in top predators like pilot whales. Faroese health authorities now warn that the meat can be hazardous, especially for children and pregnant women. It is a stark reminder that even in the most remote corners of the world, we are all geographically connected.

The Grindadráp is a phenomenon of place. It is inseparable from the deep fiords that guide the whales, the harsh climate that limited the land, and the isolation that forged an unbreakable community bond. Whether the tradition can adapt to the pressures of a modern, interconnected world remains to be seen. But its story is a powerful lesson in how the contours of the earth can carve the very soul of a culture.