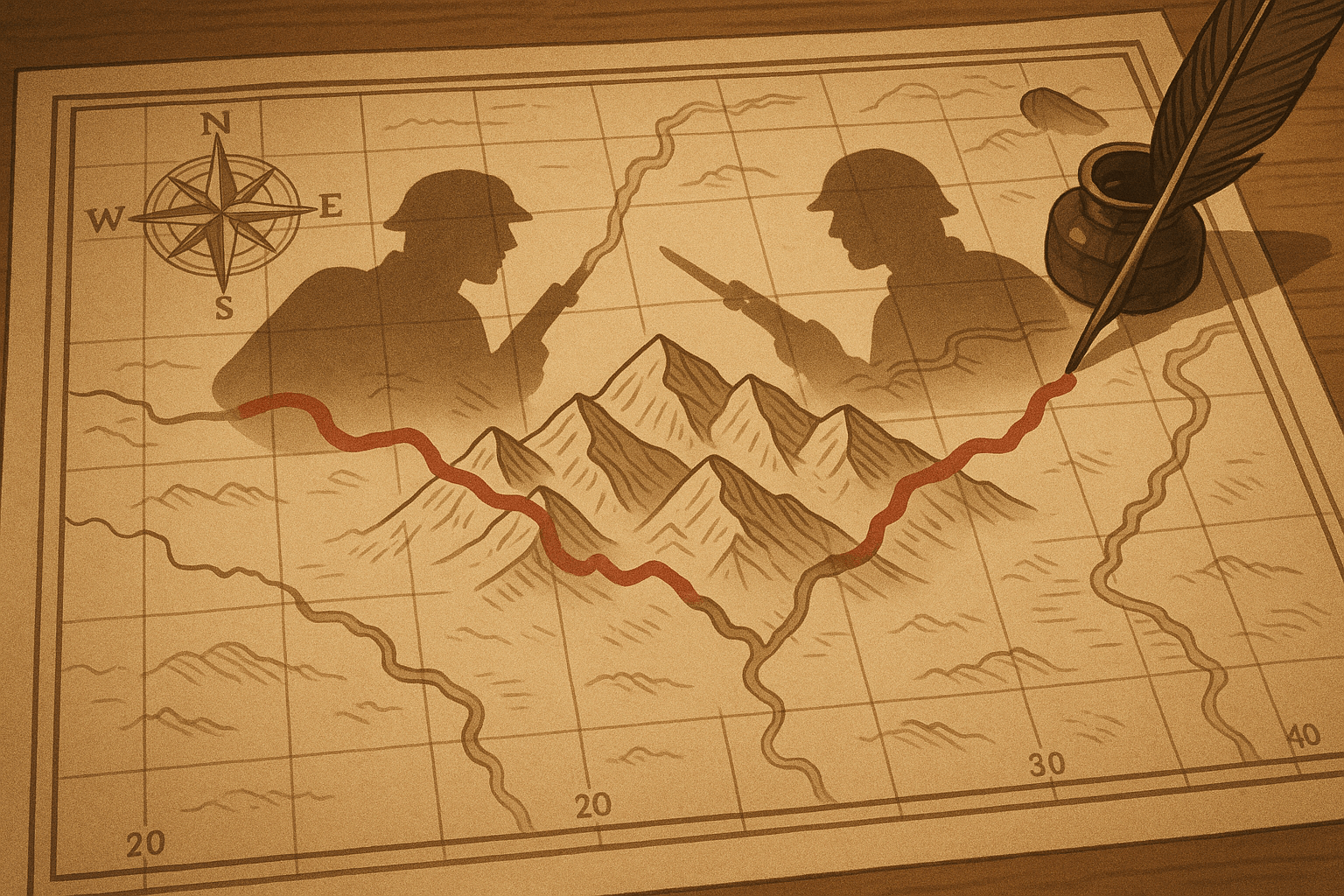

Lines on a map seem so certain, so absolute. They separate nations, define territories, and create order from a chaotic world. But what happens when those lines are wrong? What if they are drawn from a place of ignorance, based on a faulty understanding of the rivers, mountains, and people they claim to define? History shows us the answer is often conflict. Wars are rarely fought over a single cause, but lurking beneath the political rhetoric and economic ambitions, you can often find a geographic mistake—a cartographic blunder that lit the fuse.

From the dense forests of North America to the arid deserts of South America and the rugged mountains of Central Asia, let’s explore three moments where geography wasn’t just the setting for a war, but its fundamental cause.

The “Pork and Beans War”: A River Runs Through It

It sounds more like a camping mishap than an international crisis, but the “Aroostook War” was a tense, armed standoff that nearly plunged the United States and the British Empire back into conflict just decades after the War of 1812.

The source of the trouble was the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which officially ended the American Revolution. The treaty’s authors, drawing maps from thousands of miles away, used spectacularly vague language to define the border between what was then Massachusetts (the district of Maine) and British North America (New Brunswick). The boundary was meant to follow the “highlands which divide those rivers that empty themselves into the river St. Lawrence from those which fall into the Atlantic Ocean.”

This sounds simple enough, but on the ground, it was a geographic nightmare. Which “highlands” did they mean? The region is a complex web of hills and river valleys. The British claimed the line was much further south, giving them control of a vital military corridor from Halifax to Quebec. The Americans, in turn, pointed to a more northerly line dictated by the watershed. The contested territory was a 12,000-square-mile triangle of dense, valuable timberland right in the basin of the Aroostook and St. John rivers.

For decades, this ambiguity was a low-level problem. But by the 1830s, lumber was big business. Aggressive lumberjacks from Maine and New Brunswick—known as “loggers”—began pushing into the disputed territory, leading to brawls and the seizure of equipment. The conflict escalated in 1839 when Maine sent its state militia to expel the New Brunswickers. The situation spiraled: New Brunswick arrested a Maine official, Maine’s legislature authorized troops, and the U.S. Congress, not to be outdone, authorized a force of 50,000 men and a budget of $10 million—an immense sum at the time.

Cooler heads eventually prevailed, preventing a full-scale war. The “Pork and Beans War” (so-named for the troops’ primary ration) was settled by diplomacy. The 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty finally drew a clear, compromised line, splitting the territory. It was a classic case of how a failure to understand physical geography—the simple flow of water across a landscape—could bring two nations to the brink of war.

The War of the Pacific: When a Desert Became a Goldmine

The Atacama Desert, stretching along the Pacific coast of South America, is one of the driest places on Earth. For centuries, it was considered a worthless wasteland, and the border running through it between Chile, Bolivia, and Peru was poorly defined and lightly regarded. That all changed with the discovery of a new kind of gold: nitrates.

The geographic mistake here was one of foresight. The 1874 treaty between Chile and Bolivia set their mutual border at the 24th parallel south. Crucially, Bolivia agreed not to raise taxes on Chilean mining companies operating in its coastal territory (the Antofagasta province) for 25 years. This seemingly minor clause was a ticking time bomb.

In the late 19th century, nitrates (or “saltpeter”) became an incredibly valuable global commodity, essential for producing both fertilizers and explosives. The Atacama Desert, particularly the Bolivian and Peruvian portions, held the world’s richest deposits. Suddenly, this “worthless” desert was a supreme economic prize, and Chilean capital and labor poured into the region to exploit it.

In 1878, facing economic hardship, Bolivia’s government broke the 1874 treaty and imposed a new tax on the Chilean Antofagasta Nitrate & Railway Company. When the company refused to pay, Bolivia threatened to seize and auction its assets. Chile responded by sending a warship and occupying the port city of Antofagasta on the day the auction was scheduled.

The conflict exploded into the War of the Pacific (1879-1884). Peru, bound by a secret defensive alliance with Bolivia, was drawn into the fight. The war was brutal and devastating, fought on land and at sea. Chile’s superior military ultimately triumphed.

The geographic consequences were permanent. Chile annexed the entire Bolivian coastline, rendering Bolivia a landlocked nation—a status that continues to define its economy and foreign policy to this day. It also seized the valuable nitrate-rich province of Tarapacá from Peru. A border once drawn carelessly across a supposedly empty desert became the fault line for a war that redrew the map of South America, all because no one anticipated the hidden resource wealth beneath the sand.

The Durand Line: A Scar Dividing a People

Not all geographic mistakes are about misunderstanding mountains or minerals. Some are about misunderstanding people. Perhaps the most tragic and enduring example is the Durand Line—the 1,660-mile border between modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan.

In 1893, Sir Mortimer Durand, a civil servant of British India, met with Abdur Rahman Khan, the Amir of Afghanistan. Their goal was to delineate spheres of influence and create a buffer zone against perceived Russian expansion in Central Asia—a geopolitical chess match known as “The Great Game.” Durand, with little regard for the realities on the ground, drew a line on a map.

This line cut directly through the heart of Pashtunistan, the traditional homeland of the Pashtun people. It sliced through tribes, villages, and families. It severed ancient trade routes and seasonal grazing paths that had existed for centuries. It was a quintessential example of a superimposed boundary: a border imposed on a region by an outside power that ignores the existing cultural, ethnic, and social geography.

The line was never meant to be a permanent international border sealed by passports and checkpoints. But in 1947, when British India was partitioned, the Durand Line was inherited as the official border of the new state of Pakistan.

Afghanistan has never officially recognized its legitimacy. To them, the line is a colonial scar, an illegal division of the Pashtun people. This dispute has been a source of constant conflict and instability for over a century. It has fueled cross-border insurgency, terrorism, smuggling, and deep-seated political mistrust between the two nations. The rugged, mountainous terrain of the border makes it nearly impossible to police, allowing it to become a haven for militant groups.

The conflict here wasn’t sparked by a single battle but is a slow-burning, generational war rooted in a single, ignorant act of human geography—drawing a line that respected the ambitions of empires but not the lives of the people it divided.

The Enduring Power of a Line

These stories, separated by continents and centuries, share a common lesson: geography is not a passive backdrop to human history. It is an active, powerful force. A vague description of a watershed, an underestimation of a desert’s worth, or a blatant disregard for a people’s homeland can have consequences that echo for generations. These conflicts remind us that maps are not just paper; they are instruments of power, and when drawn in ignorance, they can become blueprints for war.