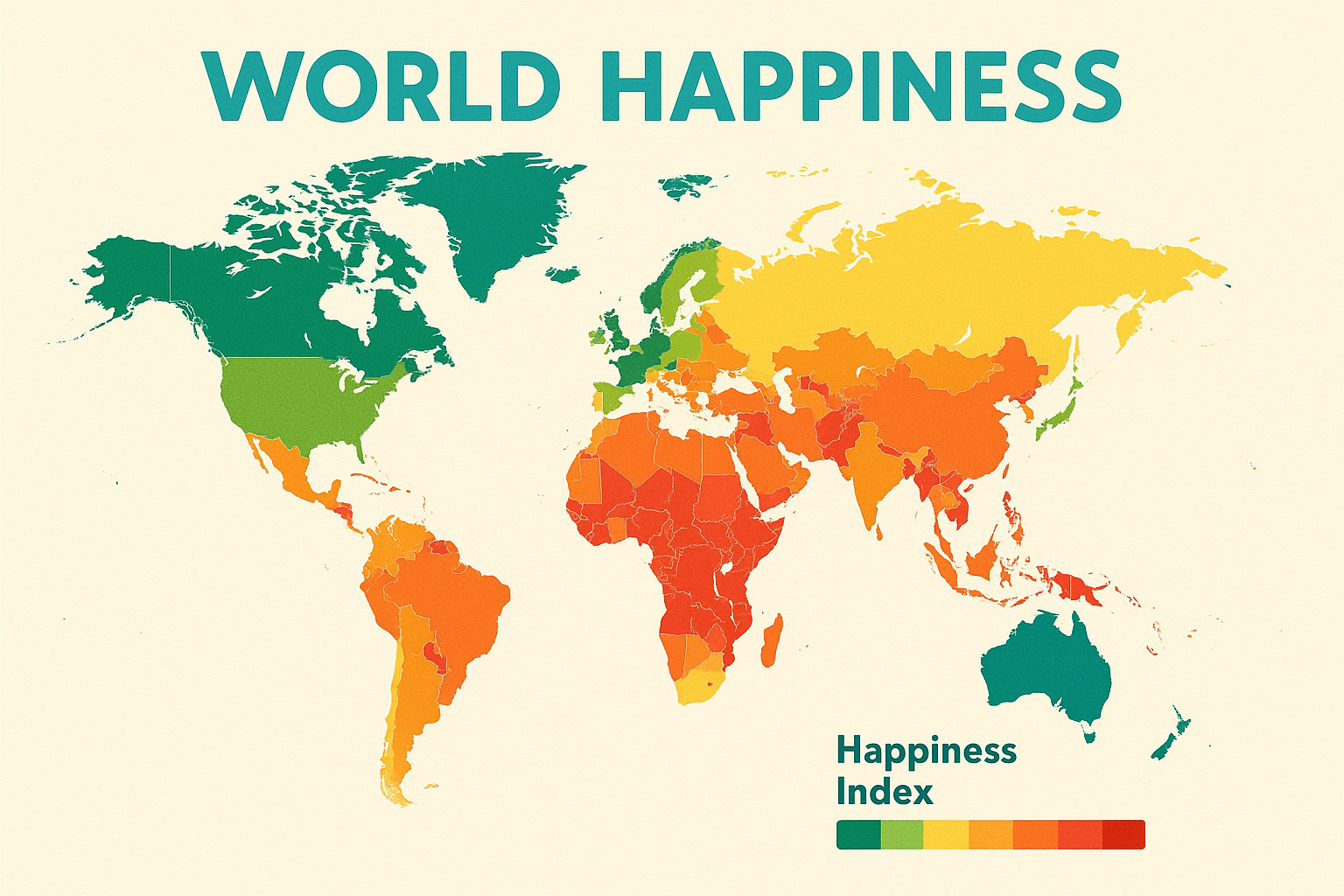

But what if the answer is less about what’s in the water and more about what’s on the map? The geography of a place—its physical landscapes, its urban blueprints, and the very way its society is spatially organized—is a powerful, often overlooked, architect of our collective well-being. Happiness, it turns out, is not just a state of mind; it’s a state of place.

The Blueprint of Bliss: Human-Scale Cities

One of the most immediate ways geography shapes our daily mood is through the design of our cities. In many parts of the world, urban planning has prioritized the car, creating sprawling, disconnected landscapes that breed isolation and stress. Happier countries, however, tend to champion a different model: the human-scale city.

Take Copenhagen, a consistent top-performer in happiness rankings. Its urban geography is a masterclass in promoting well-being. The city is famously bike-friendly, with more bicycles than people and extensive networks of dedicated bike lanes. This isn’t just a quaint feature; it’s a deliberate design choice with profound consequences. It makes commuting less stressful, incorporates physical activity into daily routines, reduces pollution, and increases spontaneous social encounters. The city’s planners focus on creating inviting public squares, car-free shopping streets, and waterfronts designed for people, not just industry. This physical infrastructure facilitates the famous Danish concept of hygge—a sense of cozy contentment and conviviality.

This principle isn’t limited to Europe. Singapore, one of Asia’s happiest and healthiest nations, has embraced a “City in a Garden” philosophy. Despite its incredible population density, the city-state has meticulously woven nature into its urban fabric. From the surreal supertrees of Gardens by the Bay to green roofs and vertical gardens adorning skyscrapers, Singaporeans are never far from green space. This biophilic design reduces the urban heat island effect, improves air quality, and provides residents with constant, calming access to nature, proving that density doesn’t have to mean misery.

Nature’s Prescription: The Power of Green and Blue Spaces

The link between nature and mental health is well-documented, and the happiest countries often have geographies that make nature profoundly accessible. This isn’t just about having pretty landscapes; it’s about a cultural and legal framework that encourages people to use them.

Finland, the reigning champion of happiness for several years, is a land of forests and lakes. But its true geographical gift is a legal concept known as jokamiehenoikeus, or “Everyman’s Right.” This ancient principle grants everyone the right to roam, camp, fish, and forage across most of the country’s natural landscapes, regardless of who owns the land. This democratizes access to nature. It’s not a privilege for the wealthy who can afford a lakeside cabin; it’s a fundamental right for every citizen. This fosters a deep, personal connection to the environment, providing a free and readily available antidote to the stresses of modern life.

Further afield, Costa Rica consistently punches above its economic weight in happiness rankings. Its national identity is built around the phrase Pura Vida (“Pure Life”), a sentiment reflected in its political geography. In 1948, the country famously abolished its army and redirected the funds towards education, healthcare, and environmental conservation. Today, over 25% of its land is protected in national parks and reserves, safeguarding its astonishing biodiversity. For Costa Ricans, happiness is tied to the pride and enjoyment of their nation’s natural wealth, a resource they chose to cultivate instead of conflict.

The Geography of Trust: Social Safety Nets and Infrastructure

Beyond the visible landscapes of cities and forests lies an invisible geography of security and trust. The social safety nets prominent in the happiest countries can be viewed as a form of human geography—a system designed to ensure that no one falls through the cracks, no matter where they live.

Universal healthcare, subsidized education, and robust unemployment benefits are not just economic policies; they are infrastructure. They create a nationwide environment where people feel secure. The anxiety of a sudden job loss or a medical emergency is dramatically reduced, freeing up mental and emotional resources. This system builds social trust—a belief that your neighbors and your government have your back. When you look at a map of Denmark or Sweden, you are also looking at a map of places where high-quality hospitals, schools, and public services are distributed equitably, creating a landscape of fairness and mutual support.

This extends to physical infrastructure. Reliable, affordable public transportation, well-maintained roads, and universal access to high-speed internet are hallmarks of happy nations. This infrastructure reduces daily friction and signals that the system works for everyone, fostering a sense of collective efficacy and fairness.

Climate, Culture, and Adaptation

It seems counterintuitive that some of the world’s happiest people live in places with long, dark, and cold winters. But geography isn’t destiny; our relationship with it is. The harsh Nordic climate has fostered remarkable cultural adaptations that build resilience and social cohesion.

When the weather outside is frightful, gathering inside becomes delightful. The cold encourages a culture of indoor socializing, from the Danish hygge to the Norwegian concept of koselig. It makes the home a sanctuary and a hub for community. Furthermore, these cultures have developed rituals to embrace the climate. The Finnish sauna is not just for bathing; it’s a cornerstone of social life and mental relaxation, a place for quiet contemplation and connection. Festivals of light, like St. Lucia’s Day in Sweden, are a powerful cultural response to the winter darkness, creating shared moments of beauty and hope.

Ultimately, the geography of happiness teaches us a vital lesson. A nation’s well-being isn’t a happy accident. It is designed, cultivated, and built into the very fabric of the land. It’s in the bike lane that takes you safely to work, the public forest you are free to explore, and the knowledge that a hospital will be there when you need it. While we can’t all move to Finland, we can advocate for the geographical principles that allow happiness to take root: human-centered cities, accessible nature, and a landscape of trust for all.