Imagine standing on the edge of a continent. Below you, the land falls away in a breathtaking, near-vertical drop, stretching as far as the eye can see in either direction. This isn’t a single cliff or a mountain peak, but a continuous, colossal step in the Earth’s crust. This is the Great Escarpment, one of the most defining—yet often overlooked—geographical features of the African continent.

Stretching for over 5,000 kilometers in a grand arc, this escarpment forms the dramatic edge of the high central Southern African plateau. It’s a geological titan that begins in Angola, sweeps south through Namibia, defines the spine of South Africa and Lesotho, and continues north through Eswatini, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique. It’s the master sculptor of the region, dictating where rivers flow, where rain falls, and where life, both wild and human, has flourished or struggled for millennia.

A Scar from a Continental Divorce

The story of the Great Escarpment begins around 180 million years ago with the violent breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana. As South America, Antarctica, and Australia tore away from Africa, the newly formed continental edge was subjected to immense geological stress. The land was pushed upwards, creating a vast, high-altitude plateau across the southern interior.

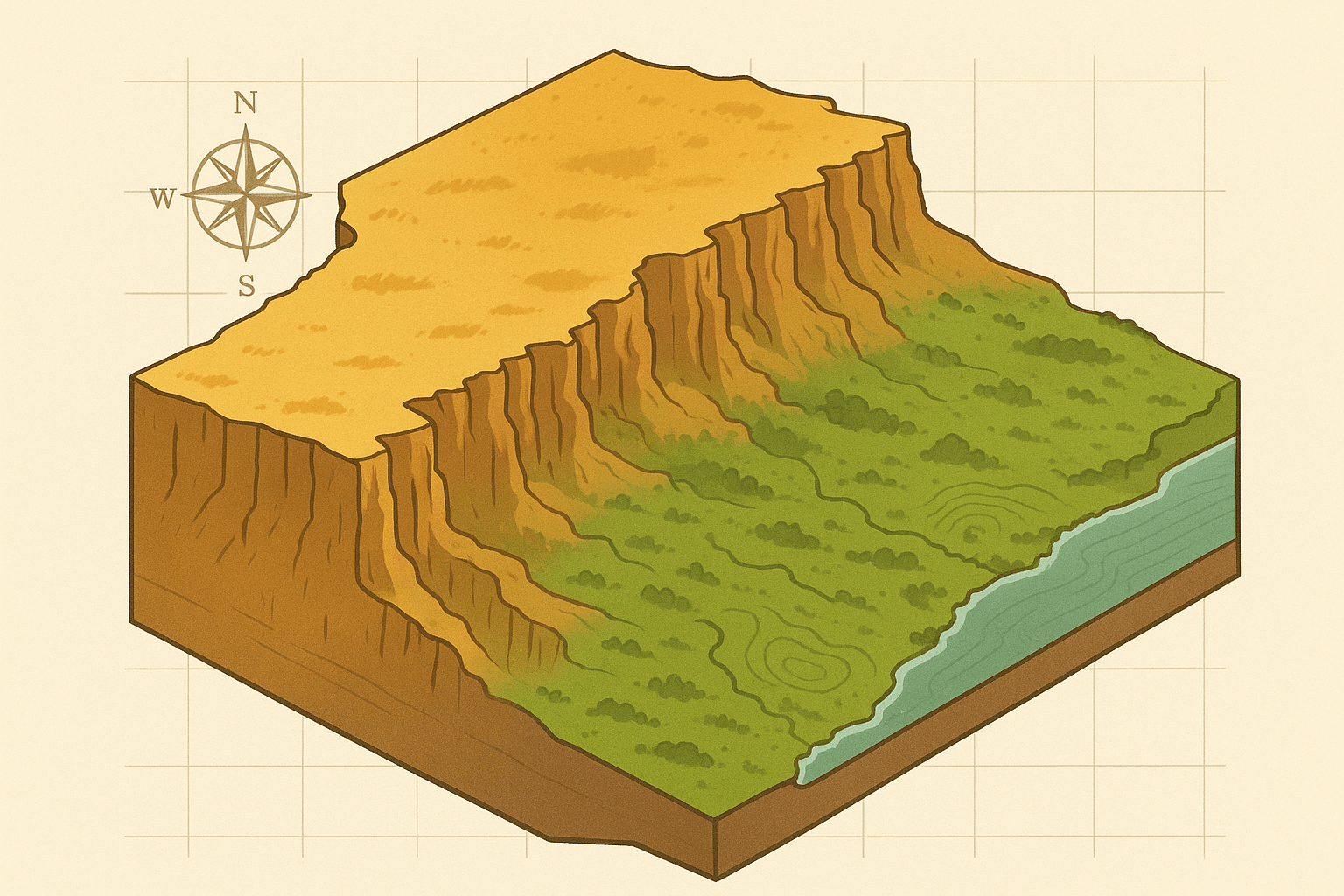

Over millions of years, erosion went to work. Rivers flowing towards the new oceans carved relentlessly into this uplifted edge, eating away at the rock and causing the escarpment to gradually retreat inland. What remains today is this sharp, steep transition zone between the high interior plateau (often over 1,500 meters) and the low-lying coastal plains. While it’s a single continuous feature, it’s known by many local names, the most famous of which is the mighty Drakensberg (Dragon’s Mountains) in South Africa and Lesotho.

The Master of Rivers and Rain

The escarpment’s most profound influence is on water. It acts as a massive continental divide, fundamentally splitting the region’s hydrology.

- Long Journeys Inland: Rivers that rise on the high plateau, like the Orange River, begin their life far from the escarpment’s edge. They meander for thousands of kilometers across the vast, flat interior of South Africa before finally reaching the Atlantic Ocean.

- Short, Steep Plunges: In stark contrast, rivers that rise on or near the escarpment’s seaward face have a much more dramatic journey. They are short, swift, and powerful, tumbling down the steep gradients in a series of waterfalls and deep gorges. The Tugela River in South Africa, for example, gives rise to the spectacular Tugela Falls, one of the tallest waterfalls in the world, as it plummets off the Drakensberg’s Amphitheatre.

This “grand edge” is also a formidable weather-maker. As moist air blows in from the warm Indian Ocean, it’s forced to rise dramatically when it meets the escarpment. This rapid ascent causes the air to cool and release its moisture as rain, a phenomenon known as orographic precipitation. The result is a lush, well-watered paradise on the coastal side, home to verdant forests and subtropical agriculture. But on the other side, the interior plateau lies in a “rain shadow.” This leeward side receives far less rainfall, creating the semi-arid conditions of the Highveld and the dry Karoo, a vast, sparse landscape of hardy shrubs and immense skies.

A Tapestry of Landscapes and Life

This sharp divide in climate and topography has created a mosaic of unique ecosystems, each with its own character.

The Drakensberg section in South Africa and Lesotho is arguably the most spectacular. Its sheer basalt cliffs, rising over 3,400 meters, create an alpine world of stark beauty. Here, you find unique Afro-alpine flora and fauna, and the entire range is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for both its natural beauty and its cultural significance—it holds the world’s most concentrated collection of San rock art.

In Namibia, the escarpment forms a brutal but beautiful boundary between the hyper-arid Namib Desert on the coast and the savanna of the interior. This transition zone is a harsh environment, yet it’s navigated by uniquely adapted desert elephants and rhinos who have learned to find water and forage along its rugged slopes.

Further north, parts of the Great Escarpment system include the Eastern Arc Mountains of Tanzania and Kenya. These isolated mountain “islands” are often called the “Galapagos of Africa” due to their incredible biodiversity and high number of endemic species—plants and animals found nowhere else on Earth.

The Human Story: A Barrier, a Refuge, a Road

For humans, the Great Escarpment has been both an obstacle and a sanctuary. For millennia, its caves and rock shelters provided refuge for the indigenous San people, whose intricate rock paintings offer a profound window into their spiritual and daily lives.

For later arrivals, the escarpment posed a formidable barrier. In the 19th century, Dutch-speaking Voortrekkers migrating from the British-controlled Cape had to find treacherous passes to haul their ox-wagons up onto the Highveld. These passes, like Van Reenen’s Pass, became vital arteries of trade and transport that are still major highways today.

The escarpment also shaped entire nations. The modern-day Kingdom of Lesotho owes its existence to the mountains. King Moshoeshoe I skillfully used the high, rugged terrain of the Drakensberg as a natural fortress to defend his people, creating a nation that is entirely surrounded by South Africa and proudly known as the “Mountain Kingdom.”

Today, the escarpment continues to shape life. Major cities like Johannesburg sit atop the cool, dry Highveld plateau, a location originally chosen for its gold-rich geology. Down on the warm, humid coastal plain, cities like Durban thrive as major ports. The escarpment is the ever-present, dramatic backdrop that separates and connects these two worlds.

From its cataclysmic birth to its role as a modern-day destination for hikers and conservationists, the Great Escarpment is far more than a line on a map. It is the physical edge that has carved the identity of a subcontinent, a silent, stony witness to the deep history of Africa’s lands, waters, and peoples.