The Geographic Stage: Life on the Edge of the Sahara

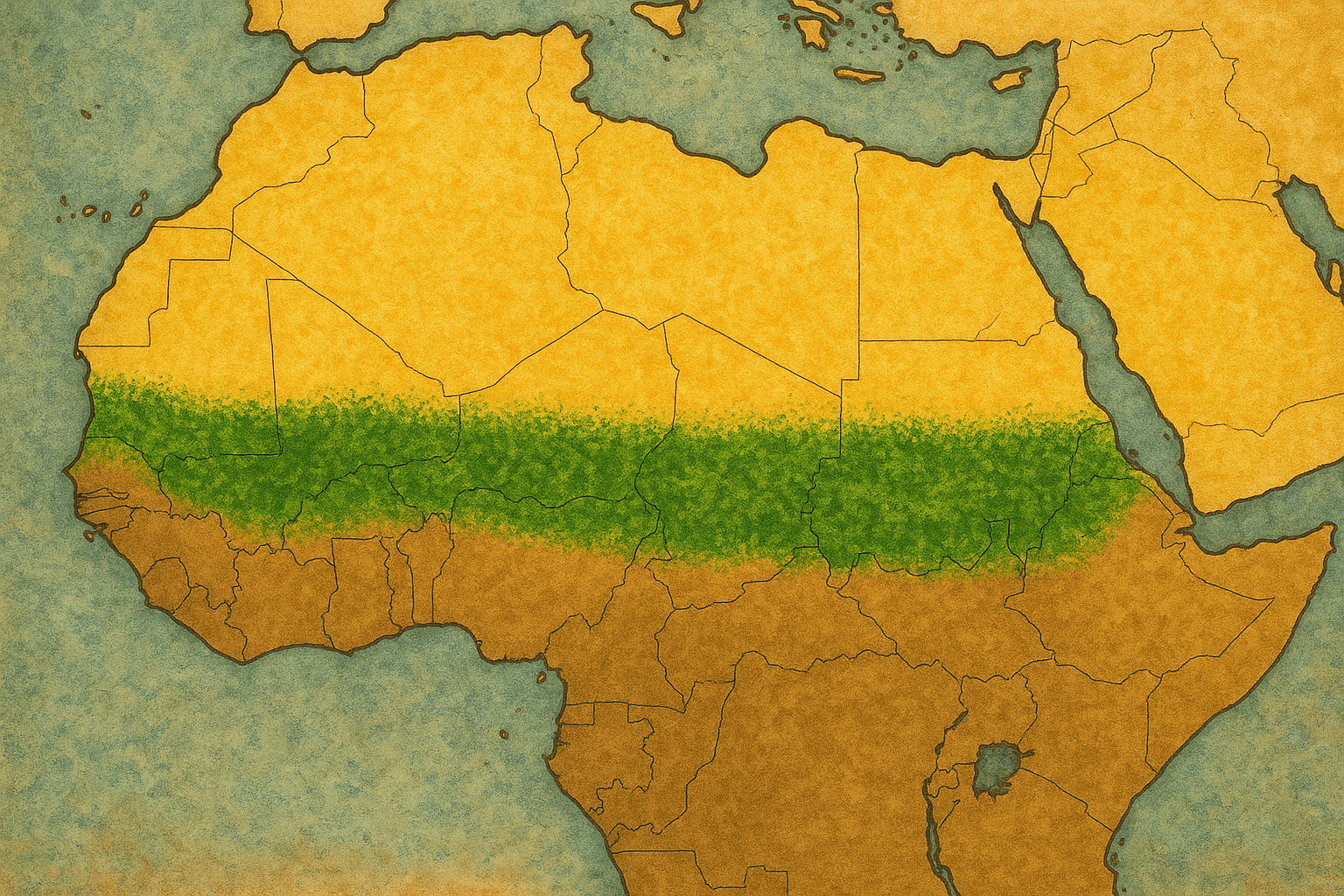

To understand the Great Green Wall, one must first understand its setting: the Sahel. The word itself, from Arabic sāḥil, means ‘coast’ or ‘shore’, a fitting name for this vast semi-arid transition zone. It is the ecological shoreline between the world’s largest hot desert, the Sahara, to the north, and the more humid savannas to the south.

Stretching across more than 10 countries—including Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, and Ethiopia—the Sahel is a landscape defined by climatic extremes. For most of the year, it is a parched, dusty expanse. But for a few short months, a volatile rainy season brings a brief, fragile flush of green. The lives of the more than 100 million people who call this region home, primarily pastoralists and subsistence farmers, are dictated by the rhythm of this rain.

However, this delicate balance is collapsing. The geographical phenomenon at the heart of the crisis is desertification. This isn’t simply the Sahara’s sand dunes “marching” south. It is the degradation of land in the Sahel itself, a process where once-productive soil becomes barren and desert-like. The primary drivers are twofold:

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures and increasingly erratic rainfall patterns are causing more frequent and severe droughts.

- Human Activity: Population growth has led to unsustainable practices like overgrazing, deforestation for firewood and charcoal, and poor agricultural techniques, which strip the land of its protective vegetation and deplete soil nutrients.

This vicious cycle entraps communities in poverty, sparks conflict over scarce resources like water and grazing land, and forces millions to migrate. The Great Green Wall was born as a direct, continent-spanning response to this creeping environmental and humanitarian catastrophe.

From a Wall of Trees to a Mosaic of Hope

The initial vision, conceived in the 1980s and formally launched by the African Union in 2007, was a literal wall of trees. The idea was to plant a continuous belt of drought-resistant acacia trees from Dakar to Djibouti, a simple, powerful image of a green barricade holding back the desert.

Over time, the project has evolved into something far more nuanced and effective. Planners realized that a monolithic wall of trees wasn’t practical or even the most beneficial solution for the diverse landscapes and communities of the Sahel. Today, the Great Green Wall is better understood as a mosaic of green and productive landscapes. The goal is no longer just stopping the desert, but regenerating the land for the people who depend on it. This involves a suite of interconnected interventions:

- Agroforestry: Integrating trees into farms to provide shade, improve soil fertility, and yield products like fruit, fodder, and medicine.

- Farmer-Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR): A revolutionary, low-cost technique where farmers protect and manage sprouts that grow from the stumps of previously felled trees. Instead of planting new saplings, they are regenerating the “underground forest” that already exists.

- Water Harvesting: Building “demi-lunes” (half-moon shaped earth bunds) or digging “zaï pits” (planting pits enriched with compost) to capture precious rainwater, allowing it to soak into the soil rather than run off.

- Sustainable Land Management: Providing communities with the tools and training to manage their land in a way that is both productive and environmentally sound.

Geopolitical Deserts and Oases of Success

Building a project on this scale across a dozen sovereign nations presents immense geopolitical and logistical challenges. The Sahel is one of the most unstable regions in the world. Political coups, extremist insurgencies, and inter-communal conflicts in countries like Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger create security vacuums that make long-term environmental work incredibly dangerous and difficult. Coordinating efforts and ensuring the transparent flow of international funding across multiple governments, each with its own bureaucracy and priorities, remains a constant struggle.

Despite these formidable hurdles, pockets of profound transformation have emerged, demonstrating the Wall’s incredible potential.

In Senegal, one of the project’s early champions, over 18 million trees have been planted across 40,000 hectares of degraded land. In the Ferlo region, restored lands now support the growth of native grasses for livestock and the sustainable harvesting of products like gum arabic, creating new economic value from the regenerated ecosystem.

Perhaps the most inspiring success story comes from Niger. Here, the power of Farmer-Managed Natural Regeneration has been transformative. Without massive international funding or large-scale tree planting, local farmers have regenerated over 5 million hectares of land—an area half the size of Portugal. By protecting and pruning existing tree stumps, they have added an estimated 200 million trees to the landscape. This has led to an additional 500,000 tons of grain production per year, dramatically improving food security for 2.5 million people.

In Burkina Faso, farmers have embraced the traditional zaï pit technique, restoring tens of thousands of hectares of completely barren, crusted land. These restored plots are now producing sorghum and millet, turning food deserts back into breadbaskets.

A New Map for the Sahel

The Great Green Wall is far behind its ambitious schedule to restore 100 million hectares by 2030. Yet, to measure it by hectares alone is to miss the point. It is more than an environmental project; it is a development corridor, a symbol of hope, and an engine for peace.

Where the Wall takes root, it changes the human geography of the Sahel. It provides food security, creates jobs in nurseries and land management, and diversifies local economies. It empowers women, who are often the stewards of the land and the keepers of traditional agricultural knowledge. By creating opportunity and restoring dignity, it offers a powerful counter-narrative to the despair that fuels conflict and forces migration.

This is an African-led solution to a global problem, a testament to the resilience of both people and nature. The Great Green Wall is slowly, painstakingly redrawing the map of the Sahel—not with ink, but with roots. It is a promise that the future of this critical region can be written not in sand, but in the life-giving shade of a forest.