A Geographical Marvel: The Lake That Was

To understand the crisis, we must first appreciate the lake’s unique geography. Lake Chad sits within a vast, shallow endorheic basin, meaning it’s a terminal lake with no outlet to the sea. Its existence has always been a delicate balancing act. Water flows in, primarily from the south, and leaves almost entirely through evaporation under the relentless Sahelian sun.

Historically, the lake’s lifeblood was the Chari River and its main tributary, the Logone River, which together supplied over 90% of its water. These rivers originate in the much wetter highlands of the Central African Republic, hundreds of kilometers to the south, and meander north into the basin. The lake’s extreme shallowness—averaging just 1.5 meters deep in its healthier days—made it incredibly sensitive. A small drop in inflow or a slight increase in evaporation could dramatically alter its size, making it a natural barometer for the region’s climate.

The geography of the lake itself is complex, traditionally divided into a northern and southern pool, separated by a marshy ridge known as the Great Barrier. As the waters have receded, this division has become stark, with the northern pool almost completely disappearing for long periods, leaving a landscape of sand dunes and scattered oases where boats once sailed.

The Disappearing Water: A Tale of Two Culprits

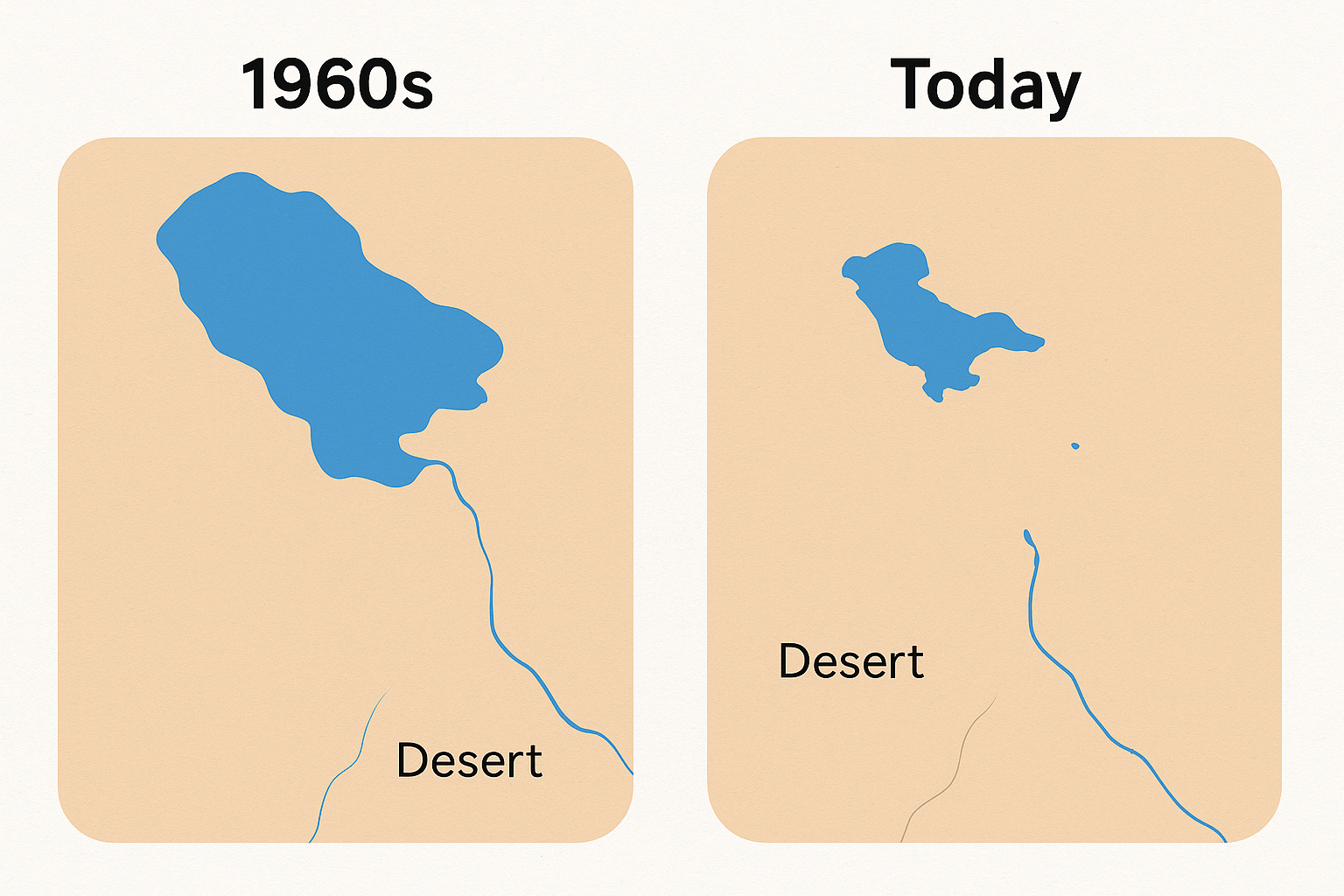

The dramatic shrinking of Lake Chad is a textbook case of human-environment interaction, driven by two powerful forces: a changing climate and unsustainable water management.

Climate Change: The Shifting Sands of the Sahel

The most significant natural factor has been a drastic shift in regional climate patterns. The devastating Sahelian droughts of the 1970s and 1980s were a turning point. Rainfall across the entire catchment area plummeted, sometimes by as much as 30%. This had a direct and immediate impact on the Chari and Logone rivers, reducing the volume of water flowing north into the lake. Simultaneously, rising global temperatures have increased the rate of evaporation, meaning the water that does reach the lake disappears more quickly. This one-two punch from climate change fundamentally disrupted the lake’s delicate hydrological balance.

Human Geography: The Thirsty Landscape

While climate change set the stage, human activity has massively amplified the problem. The population in the Lake Chad Basin has exploded, growing from around 20 million in the 1960s to over 50 million today. This burgeoning population, spread across four nations—Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon—has placed an enormous demand on the basin’s water resources.

Large-scale irrigation projects, developed to boost food production, have diverted vast quantities of water from the rivers that feed the lake. Nigeria’s South Chad Irrigation Project (SCIP), for example, was designed to draw water from the lake to irrigate tens of thousands of hectares of farmland. Similarly, dams built on feeder rivers, such as those on the Hadejia-Jama’are river system that flows into the Komadugu-Yobe River (the lake’s second-largest source), have significantly reduced downstream flow. This “death by a thousand cuts” from uncoordinated, upstream water use has starved the lake of the water it needs to survive.

The Human Cost: A Crisis on the Map

The shrinking of Lake Chad has left more than just a dry lakebed; it has created a cascading humanitarian and security crisis that radiates across the region.

- Geopolitical Flashpoints: As the water recedes, international borders that were once clearly defined by the lake have become ambiguous and contested. Islands that belonged to one country are now connected to the mainland of another. This has ignited disputes over land, fishing rights, and access to the remaining water between communities and countries.

- Livelihoods Lost: The lake once supported a vibrant economy based on fishing, farming on the fertile floodplains (known as wadis), and pastoralism. The collapse of the fishery alone has destroyed the livelihoods of millions. Fishermen have been forced to become farmers on marginal land, and pastoralists must travel ever-further distances to find water and pasture for their herds, often leading to conflict with settled agricultural communities.

- Displacement and Instability: The economic collapse has fueled one of the world’s largest displacement crises. Millions of people have been forced from their homes, becoming refugees or Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in overburdened cities like Maiduguri in Nigeria and Diffa in Niger.

- A Fertile Ground for Insurgency: The crisis has created a vacuum of governance, widespread poverty, and a desperate, jobless youth population. This provided the perfect recruiting ground for extremist groups like Boko Haram and its offshoot, the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP). The remaining swampy, maze-like islands of the lake offer ideal hideouts, making the region notoriously difficult to police and further destabilizing the entire basin. The geography of the shrinking lake has, in effect, become a geography of conflict.

Charting a Course Forward: A Geographical Challenge

Tackling the Lake Chad crisis requires solutions as complex as its causes. The Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC), representing the four core countries plus others in the basin, is coordinating efforts, but the challenge is immense.

One ambitious, and highly controversial, proposal is the Transaqua project—a mega-engineering scheme to replenish the lake by diverting water from the Congo River Basin via a 2,400-kilometer canal. While geographically fascinating, critics point to the immense cost, potential environmental impacts on the Congo Basin, and geopolitical hurdles.

More realistic approaches focus on better transboundary water management, promoting water-efficient irrigation, restoring degraded ecosystems, and providing alternative livelihoods for the affected population. Ultimately, any lasting solution must address the intertwined geographical realities of climate change, resource management, economic development, and regional security. The future of this vast region is inextricably tied to the fate of its shrinking oasis.