The River’s Geography: A Tale of Two Niles

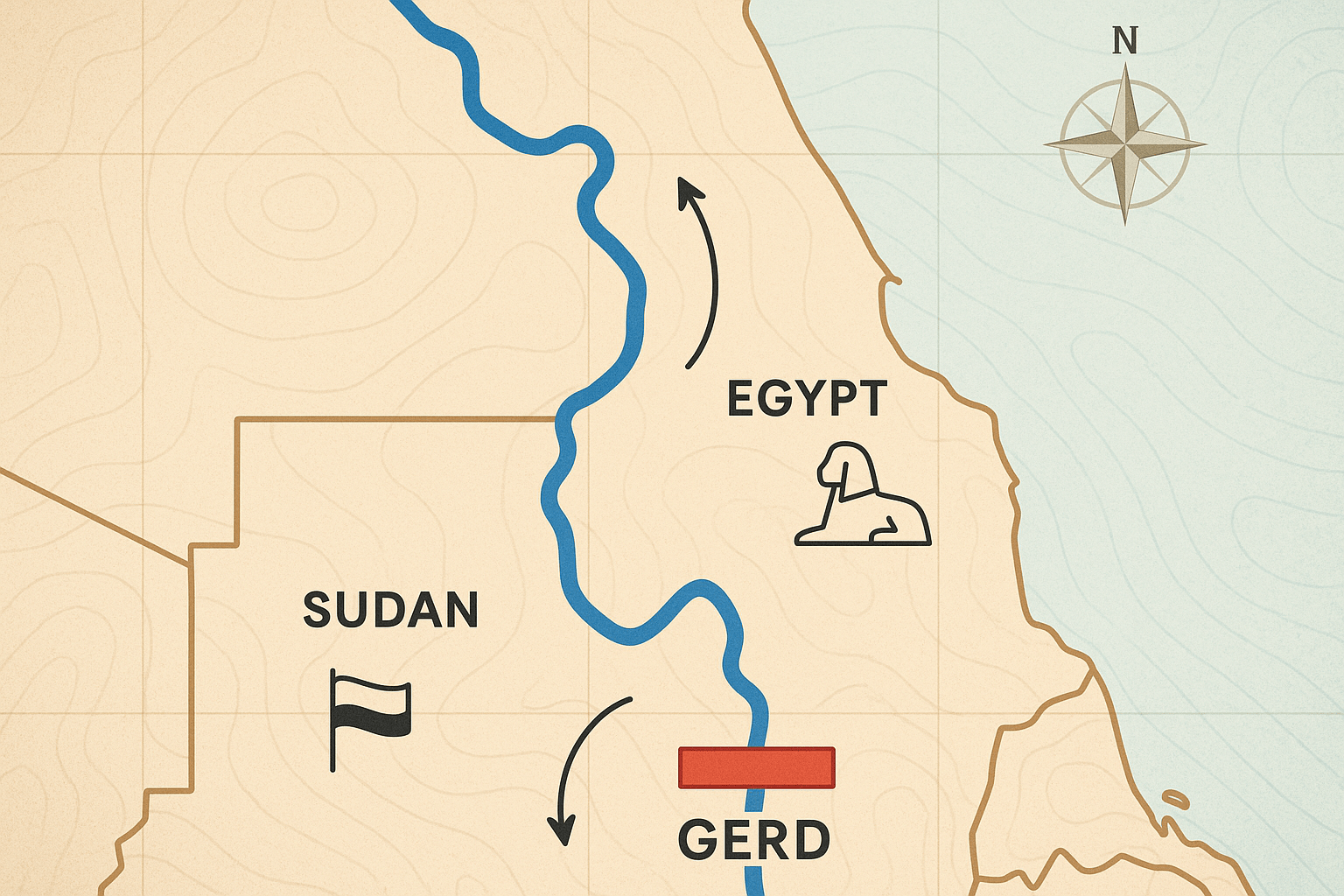

To understand the current crisis, one must first understand the Nile’s physical geography. The world’s longest river is not a single entity but is fed by two main tributaries: the White Nile and the Blue Nile.

The White Nile, originating in the Great Lakes region of Central Africa, provides a steady, reliable flow throughout the year. But it is the Blue Nile that is the river’s powerhouse. Gushing from Lake Tana in the high-altitude, rain-drenched Ethiopian Highlands, the Blue Nile is a force of nature. During the summer monsoon season, it becomes a raging torrent, contributing a staggering 85% of the Nile’s total water volume and carrying the rich, fertile silt that historically nourished the floodplains downstream.

This geographical reality creates a fundamental asymmetry of power:

- Ethiopia: The “water tower” of Africa. Its highlands are the source of this immense aquatic wealth, yet due to steep gorges and a history of poverty and instability, it has never been able to harness this resource.

- Sudan: The meeting point. In its capital, Khartoum, the tranquil White Nile merges with the turbulent Blue Nile. Sudan is both a downstream nation to Ethiopia and an upstream nation to Egypt, placing it in a uniquely complex position.

- Egypt: The “gift of the Nile.” As the Greek historian Herodotus famously wrote, Egypt’s existence is almost entirely predicated on the river. Over 97% of its 110 million people live crammed into a narrow strip along the Nile and its delta, in an otherwise hyper-arid landscape.

The GERD: A Symbol of Sovereignty and Development

In the Benishangul-Gumuz region of Ethiopia, just 15 kilometers from the Sudanese border, the GERD rises from the Blue Nile’s gorge. When complete, it will be the largest hydroelectric dam in Africa, creating a reservoir—the size of Greater London—that will hold up to 74 billion cubic meters of water. Its goal is to generate over 6,000 megawatts of electricity, more than doubling Ethiopia’s current output.

For Ethiopia, the dam is about more than just power. It is a profound symbol of national pride, sovereignty, and the dawn of a new era—a “Renaissance.” Financed largely through public contributions and government bonds, the project represents a declaration that Ethiopia will no longer watch its most valuable natural resource flow away untapped. With over 60% of its population lacking access to electricity, the GERD is presented as a non-negotiable key to industrialization and lifting millions out of poverty.

Egypt’s Existential Fears: A View From Downstream

For Cairo, the GERD is not a symbol of progress but an existential threat. Egypt’s perspective is shaped by two powerful forces: geography and history. Geographically, it is the last country on the river’s path to the sea, leaving it utterly vulnerable to any actions taken upstream.

Historically, Egypt has relied on colonial-era treaties to secure its access. A 1959 agreement with Sudan (which built upon a 1929 Anglo-Egyptian treaty) allocated the vast majority of the Nile’s flow to Egypt and Sudan, even granting Egypt veto power over any upstream construction projects. Ethiopia, which was never a signatory, vehemently rejects these agreements as relics of a colonial past that ignored the rights of source nations.

Egypt’s primary fears are centered on the rate at which Ethiopia fills the dam’s massive reservoir:

- Reduced Water Flow: A rapid fill, especially during a drought year, could drastically reduce the volume of water reaching Egypt, crippling its agricultural sector which depends on the Nile for 98% of its irrigation.

- Impact on the Aswan High Dam: The GERD’s operation could interfere with the functioning of Egypt’s own mega-dam at Aswan, which is critical for regulating water flow, generating electricity, and ensuring year-round water supply for its cities and farms.

- Economic and Social Devastation: Even a small, sustained reduction in flow could have catastrophic consequences for Egypt’s food security, economy, and social stability.

For Egyptians, control over the Nile is a matter of national security, woven into the very fabric of their identity for 5,000 years.

Sudan: Caught in the Middle

No country embodies the complexities of the GERD standoff more than Sudan. Geographically positioned between the two main antagonists, its stance has been ambivalent and has shifted with its volatile internal politics.

On one hand, Sudan stands to benefit significantly from the GERD. The dam will regulate the Blue Nile’s flow, smoothing out the devastating seasonal floods that regularly inundate areas around Khartoum. It will also trap the vast quantities of silt that currently clog Sudan’s own dam reservoirs, such as the Roseires Dam, extending their operational lifespan. Furthermore, Sudan could purchase cheap, clean electricity from its neighbor.

On the other hand, the risks are immense. The proximity of the GERD to its border means that any mismanagement or, in a worst-case scenario, a structural failure of the dam would be utterly catastrophic for Sudan’s population centers downstream. Sudan shares Egypt’s demand for a legally binding agreement on the dam’s operational data and safety protocols.

A River of Distrust

For over a decade, negotiations brokered by the African Union, the United Nations, and the United States have failed to produce a breakthrough. The core of the dispute is trust—or the profound lack of it. Ethiopia insists on its sovereign right to fill and operate the dam as it sees fit, viewing Egyptian and Sudanese demands for a binding agreement as an attempt to codify an unjust status quo.

Egypt and Sudan argue that without a legally binding treaty that includes drought mitigation clauses and clear rules for operation, their water security is subject to the whims of Addis Ababa. This clash between Ethiopia’s right to develop and the downstream nations’ right to exist has created a dangerous diplomatic impasse.

The GERD standoff is a quintessential 21st-century conflict, where climate change, population growth, and national ambition converge on a single, vital geographical feature. The Blue Nile, which has given life to this region for eons, is now a powerful symbol of division. Finding a path to cooperative management is not just a diplomatic challenge; it is an urgent necessity for the peace and prosperity of over 250 million people who depend on its life-giving waters.