The Geographical Stage: A Karst Wonderland

To understand Plitvice, we must first look at its foundation. The park is located in the Dinaric Alps, a region dominated by karst topography. This is a landscape formed from the dissolution of soluble rocks like limestone and dolomite. Think of it as a giant, porous sponge. Rainwater, slightly acidic, seeps into the ground, carving out underground rivers, caves, and sinkholes. This water becomes super-saturated with dissolved minerals, particularly calcium bicarbonate, as it travels through the rock.

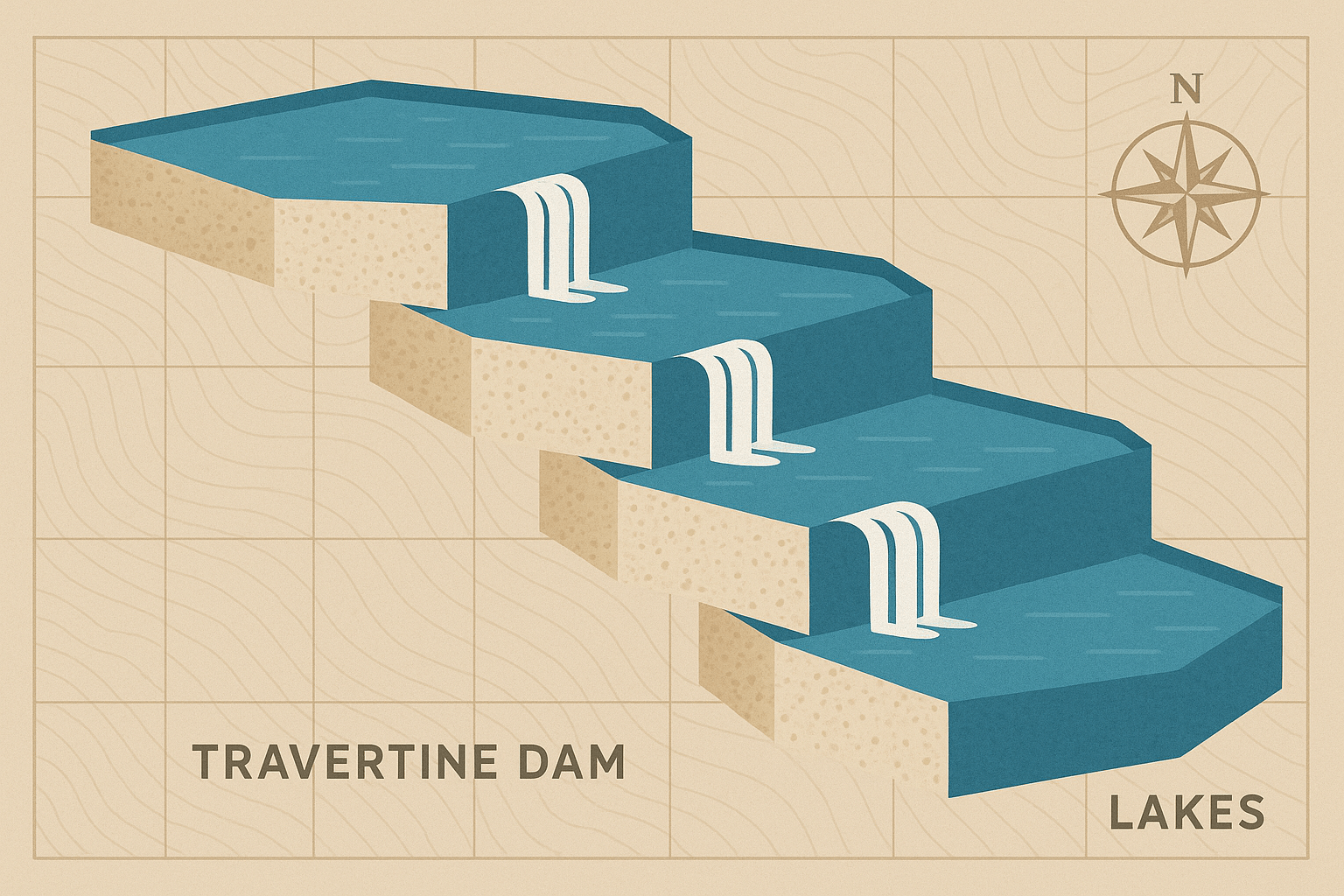

This mineral-rich water is the essential raw material for the spectacle that is Plitvice. The entire system is fed by several small rivers and subterranean karst springs, which emerge to form the headwaters of the Korana River. But instead of simply carving a single river channel down the valley, something extraordinary happens: the river starts building its own barriers.

The Heart of the System: Travertine, Nature’s Mason

The secret ingredient that transforms Plitvice from a simple river valley into a terraced wonderland is travertine. Travertine is a form of limestone, but its formation here is a fascinating biological and chemical process known as tufa deposition.

It’s a multi-step process that works like a natural assembly line:

- Step 1: Mineral-Rich Water: As we know, the water flowing into the lakes is loaded with dissolved calcium bicarbonate (Ca(HCO3)2) from its journey through the limestone bedrock.

- Step 2: Agitation and Aeration: As this water tumbles over rocks, logs, and other obstacles, it gets agitated. This turbulence causes carbon dioxide (CO2) to be released from the water into the air.

- Step 3: The Chemical Shift: The loss of CO2 changes the water’s chemistry, making it less acidic. This chemical shift makes it impossible for the water to hold onto its high concentration of dissolved minerals. Consequently, calcium carbonate (CaCO3) — the building block of limestone and travertine — begins to precipitate, or solidify, out of the water.

- Step 4: The Biological “Glue”: This is the most critical part. The surfaces of the rocks, branches, and mosses in the river are coated in a slimy biofilm of algae, bacteria, and other microorganisms. This sticky layer acts like natural flypaper, trapping the tiny calcite crystals precipitating from the water. As these organisms photosynthesize, they consume more CO2, further accelerating the precipitation process around them.

Over centuries and millennia, layer upon layer of this calcite encases the moss and algae, which continue to grow on top. The result is a porous, ever-growing natural dam of travertine. It is this process, repeated over and over, that has built the barriers separating the sixteen lakes.

A Staircase of Lakes: The Upper and Lower Systems

The Plitvice Lakes system is not one uniform body but is traditionally divided into two clusters, defined by their underlying geology and distinct character.

The Upper Lakes (Gornja Jezera)

This group consists of 12 larger lakes formed in a wider valley made of less soluble dolomite rock. The dams here are more heavily vegetated, and the slopes are gentler. The flow of water between them creates broad, intricate cascades that weave through lush forests. The two largest lakes, Prošćansko and Kozjak, anchor this upper system, setting a serene and expansive tone.

The Lower Lakes (Donja Jezera)

Further downstream, the landscape dramatically changes. The four Lower Lakes are smaller, deeper, and set within a steep, imposing limestone canyon. Here, the process of canyon-cutting by the river competes with the dam-building of the travertine. The waterfalls are more powerful and concentrated, culminating in the park’s breathtaking finale: the Veliki Slap, or “Great Waterfall.” At 78 meters (256 feet), it is the tallest waterfall in Croatia, formed by the Plitvica stream plummeting over the limestone cliff to join the final lake of the system.

The Science of a Spectacle: Dynamic and Ever-Changing

What makes Plitvice a true geographical phenomenon is that it is a living landscape. The travertine dams are not static, ancient relics; they are actively growing. Scientists estimate that the dams grow at an average rate of about 1 centimeter per year. This means the Plitvice you see today is different from the one visited 50 years ago, and different still from the one future generations will witness. Waterfalls can appear or disappear, the shapes of lakes can shift, and new dams can begin to form.

This dynamism also highlights the system’s fragility. The delicate balance of pH, temperature, and microbial life is essential for travertine formation. Pollution or physical disturbance can halt the process. This is why strict conservation rules are in place, including the famous prohibition on swimming. The oils, sunscreens, and general disruption from swimmers could kill the vital microorganisms and stop the magic in its tracks.

Even the mesmerizing colors of the lakes—ranging from azure and emerald green to deep blue and grey—are a direct result of this unique hydrology. The hues are determined by the concentration of suspended travertine particles, the depth of the water, the amount of organic matter, and the angle of the sunlight, painting a different masterpiece every hour of every day.

Plitvice Lakes National Park is more than just a beautiful place; it’s a vibrant, open-air laboratory demonstrating how geology and biology can conspire to create one of Earth’s most stunning architectural feats. It’s a powerful reminder that our planet is a constantly evolving work of art, powered by processes both grand and microscopic.